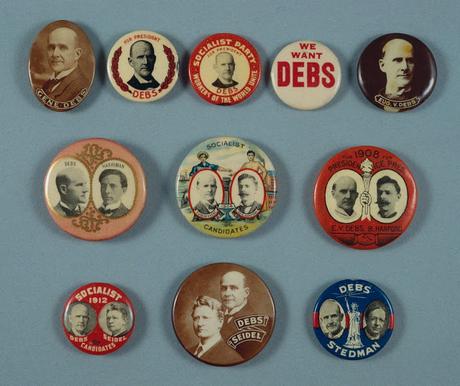

Socialist ideas seem to be making a comeback in the United States these days, especially among young people. But I wonder how many of them know that this country once had a vibrant and growing socialist movement. And the movement was led by a charismatic leader -- Eugene V. Debs.

Debs is one of my personal heroes, so I was delighted to see this article on him in The New York Times. It is an excellent look at Mr. Debs -- written by Maurice Isserman (professor of history at Hamilton College). Here 's just part of what he has written:

One hundred years ago this month, the American Socialist leader Eugene V. Debs, reported to a penitentiary in Moundsville, W.V., to begin a 10-year prison term. Debs had been convicted the previous fall of violating the Espionage Act, which had been enacted shortly after the United States entered World War I with the ostensible aim of punishing citizens who provided aid to the enemy. By the time Debs went to prison, scores of his fellow Socialists had already been imprisoned under the act’s provisions.

Approaching his 64th birthday in ill health, depressed and dreading separation from family and friends, Debs did not crave martyrdom. But he knew he had a role to play, one he had freely chosen, and thus remained outwardly defiant. “Tell my comrades,” Debs declared on beginning his sentence in April 1919, “that I entered prison doors a flaming revolutionist, my head erect, my spirit untamed and my soul unconquered.”

Debs’s crime, in fact, had nothing to do with “espionage,” or any other devious act of subterfuge and disloyalty. His was a crime committed proudly in the open: delivering a speech before a cheering crowd of a thousand supporters in a public park in Canton, Ohio, some 10 months earlier. Debs deeply opposed the war, and said so, and was punished for it. When he entered prison, Helen Keller, herself a veteran Socialist, called him an “apostle of brotherhood and freedom.”

Debs dedicated his career to showing that another, more equitable America was possible; a century later, as the country once again wrestles with the same question, it’s worth remembering what Debs tried to tell us. . . .

In 1893 he helped form and became president of the American Railway Union, which enjoyed a brief but phenomenal success, climaxing in the great Pullman strike of 1894. The strike was broken by federal troops, and Debs was subsequently thrown in prison for interfering with the mails. The union’s demise, and the six months he spent in jail, sent Debs on a political trajectory that in a few years’ time saw him emerge as the presidential standard-bearer for a small but growing Socialist movement.

“Even physically Debs seemed to change,” his biographer Nick Salvatore wrote. He took on national stature after the turn of the century, and won hundreds of thousands of supporters for the Socialist movement. . . .

“Promising indeed,” Debs wrote in September l900, “is the outlook for Socialism in the United States. The very contemplation of the prospect is a wellspring of inspiration.”

Debs was exaggerating; that year, as a Socialist presidential candidate, he won just a 100,000 votes out of nearly 14 million cast. But in the presidential bids that followed, hyperbole began to edge toward prophecy.

In 1912 he won nearly a million votes, some 6 percent of the total. Immigrant neighborhoods on the Lower East Side and in Milwaukee were not the only places to turn out for Debs. In some states, such as Washington and California, and most surprisingly, Oklahoma, the Socialist Party’s share of the vote climbed into the double digits. Over the same 12-year period, the party expanded its membership from 10,000 to nearly 120,000. Across the country, 1,200 Socialists won public office, including mayors from Flint, Mich., and Butte, Mont., to Berkeley, Calif.

Not without personal vanity, Debs nevertheless viewed his considerable charismatic gifts with a measure of detachment. The point of his constant speaking tours crisscrossing the country was not to build an individual cult, but to develop an institutional base. “I don’t want you to follow me or anyone else,” he declared in 1910. “If you are looking for a Moses to lead you out of this capitalist wilderness, you will stay right where you are.” He would not presume to lead his followers into the “promised land,” even if it was in his power to do so, “because if I could lead you in, someone else could lead you out.”. . .

During his time in prison the Socialist movement, battered by official repression, fell to pieces. In a note from prison to his lover Mabel Curry, Debs related a dream he had as he slept uneasily, as he often did, on the cot in his cell: “I was walking by the house where I was born — the house was gone and nothing left but ashes. All about me were ashes. My feet sank in them and my shoes filled with them.”

And so the prospects for a revived American Socialism remained for most of the ensuing century, in ashes. Whether a current generation of Socialists, new to the movement and growing in numbers, will find a way to weave together the redemptive promise of moral protest and the practical achievements of political action is still to be determined.