When I was a kid we didn’t have television or hand-held devices. We had to make bricks from bitumen and pitch. My friends and I liked to say “bitumen” over and over until our mothers yelled at us for being obscene. She said we didn’t even know what it was. But we found out soon enough.

I remember what it was like having to build the pyramids. Talk about a fat-burning exercise. There wasn’t even any Snapple. If we were lucky our Egyptian taskmasters would give us water, and sometimes Gatorade when the Pharaoh and Players’ Association were able to work out a contract.

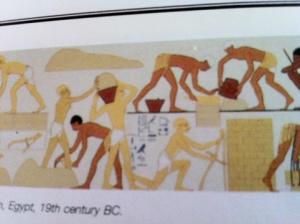

The work was horrible. We had to mix straw with this sticky black stuff by stomping on it all day long for days and days. At first it was kind of fun, and I would sing songs to go along with the stomping. Then a taskmaster whipped me and told me to sing something in a lower key.

Then they had me moving these giant blocks on rollers. On the third day I developed a persistent ache in my left calf and asked the nearest taskmaster where I could find some cortisone.

“You Hebrews are always complaining,” he said. “Get back to work or I will whip you to death and then make a note in your file.”

“But why do these blocks have to be so big?” I asked. “Couldn’t you build pyramids with small bricks? Or maybe wood planks or vinyl siding? I hear vinyl siding does very well in the desert.”

The taskmaster raised his whip again and I made the sound of it cracking and threw myself back violently, leaving the taskmaster looking confused.

In the evenings I would hang out with my friends. It was always a big debate about where we would go.

“How about your place?” I would ask my friend Yaakov. “What’s going on there?”

“My parents are sitting around exhausted from back-breaking work, and are praying for the deliverance that is supposed to be coming.”

“What about you, Naftali? Anything cool going on at your hut?”

“My parents are sitting around exhausted from back-breaking work, and are praying—”

“Okay, okay. Hmm. Let’s see who’s at the Dairy Queen.”

It wasn’t easy coming of age during this time. Everyone was depressed because we were slaves, and the rumor that we were going to be saved by divine intervention was starting to sound like one of those stories parents tell their children when they won’t go to bed. I myself was pretty skeptical and suggested that we Hebrews all go on strike until we were released from the house of bondage and given a lower co-pay on our health insurance.

“We could do it during the holidays,” I said. “All the last-minute shoppers will be screwed. The store owners will lose millions!” But then the elders cited a law that said any striking Hebrew would be tossed into the Nile and then barred from attending the annual picnic.

And then one day we were told to pack everything up because we were leaving. Apparently this guy Moses and his brother Aaron had performed some dog and pony show for the Pharaoh and gotten him to agree to let us go.

“Go where?” I asked.

“To the Promised Land. The land of our fathers Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.”

“Well my father’s name is Steven,” I said, “and his land is right over there behind that pile of animal dung.”

But it was true—we were leaving Egypt and I had to spend the whole day going through all the boxes filled with all my notebooks and artwork from school.

“Mom, look,” I said to my mother who was racing around the kitchen shoving food in cloth bags. “Here’s a story I wrote in second grade. Didn’t I have fantastic penmanship?” Then she shoved a piece of unleavened bread in my mouth and told me to hurry up.

I’ll spare you the boring details of the days that followed. It’s all written down somewhere anyway. We left Egypt and wandered around the desert for years and years, and I was surrounded by all these smarmy teenagers who knew nothing of the Pharaoh or what had been like to be slaves. I tried to tell them about it, about the history of our people and what it meant to be free.

But all they cared about was their rock music and who was going to the Dairy Queen.