Three takes on the argument that religious people in the U.S. deserve special rights when it comes to the "right" to discriminate against gay folks (and how that argument is a direct descendant of the very same argument offered by white Southerners resisting integration in the 20th century):

At Truthdig, Kathleen Franke, director of Columbia University's Center for Gender and Sexuality Law, points out that the "religious freedom" crowd want to use religion as a "trump card — you throw it down, it’s a conversation stopper, and we don’t know how to get out of this impasse." She notes that this is precisely the tactic that many Southerners used to resist integration, maintaining that God had separated the races and it violated their religious freedom to ask them to integrate--an argument that, as Franke observes, the Supreme Court rejected when Bob Jones University tried it:

Really since the late 19th century, when opponents of expanding notions of equality have lost in the public arena, their plan B has been to seek refuge in religion. We first saw it in racial equality cases, and more recently in the areas of reproductive rights and gay rights. When Congress or a state legislature or a federal court mandates the integration of public schools or upholds sex equality in the workplace or allows same-sex couples to marry, opponents of those efforts fall back on religion to say, “You can have those laws, they just don’t apply to me.”

At the Crooked Timber site, Henry Farrell counters Conor Friedersdorf's argument that the religiously-propped racial bigotry of white Southerners resisting integration is somehow different in kind from the religiously-propped homophobic bigotry of Christians refusing to bake cakes for or sell flowers to same-sex couples:

Bigotry derived from religious principles is still bigotry. Whether the people who implemented Bob Jones University’s notorious ban on inter-racial dating considered themselves to be actively biased against black people, or simply enforcing what they understood to be Biblical rules against miscegenation is an interesting theoretical question. You can perhaps make a good argument that bigotry-rooted-in-direct-bias is more obnoxious than bigotry-rooted-in-adherence-to-perceived-religious-and-social-mandates. Maybe the people enforcing the rules sincerely believed that they loved black people. It’s perfectly possible that some of their best friends were black. But it seems pretty hard to make a good case that the latter form of discrimination is not a form of bigotry. And if Friedersdorf wants to defend his sincerely-religiously-against-gay-marriage people as not being bigots, he has to defend the sincerely-religiously-against-racial-miscegenation people too. They fit exactly into Friedersdorf’s proposed intellectual category.(I'm indebted to Fred Clark at Slacktivist for the link to Henry Farrell's Crooked Timber posting.)

And at Religion Dispatches, Eric Miller notes that conservative Christians have sought to corner the Christian market in the U.S., effectively fusing Christianity and right-wing politics, while excluding all other readings of the Christian gospels as illicit interpretations of Christianity:

American Christianity and American Conservatism have been blended to a degree that makes them difficult to distinguish. In this environment, the “religious conservative” qualifier usually serves as a synecdoche for the “social” and “economic” varieties as well. For many American Christians, to be one is to be the rest.

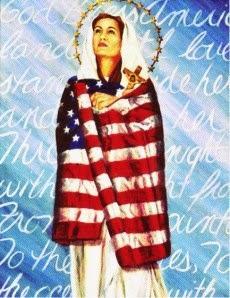

On the graphic, Our Lady of 'Merica, which the Catholic diocese of Brooklyn distributed as part of the U.S. Catholic bishops's "Fortnight for Freedom" events in 2013, see Robert Christian at Millennial.