"Globalisation isn't as simple – or as flat – as you might think," writes Andrew Bowman, "It's uneven and has been knocked by the financial crisis. In some ways, the world is becoming less globally connected and more regionally-orientated, in contrast to most assumptions." ["Forget globalisation – it's regional connections that are key," For years I have been insisting that regionalization would become an increasingly obvious characteristic of globalization (my most recent posts on the subject were entitled Globalization: Retreating or Transforming? and There's Room for More Globalization). In these posts, I cited the work of Professor Pankaj Ghemawat of IESE Business School in Spain, who argues that globalization has not, in fact, penetrated all that deeply into most economies. For more on his views, read "The case against globaloney." [The Economist, 20 April 2011] The evidence for the regionalization trend is starting to stack up. Bowman bases his observation on "the findings of the global connectivity index created by academics from the IESE Business School, which sheds light on the current state of globalisation with interesting results." Ghemawat led the team that conducted this DHL-sponsored study. Bowman writes:

"The standard globalisation thesis posits the limitless movement of capital and information and the inexorable weakening of national boundaries and identities – and this school of thought remains as strong as it ever was at the height of the 'new economy' mania. However, the IESE study ... suggests that in some key areas global interconnectedness has actually been declining, and that regional connections are as significant as global ones in driving increased productivity."

These conclusions shouldn't be all that surprising. Regional countries generally share more common interests with each other than with countries half-way around the globe. It's also easier and cheaper to move goods and people between nearby neighbors. Culture and language also play a role in the rise of regionalization. Nevertheless, Bowman insists that many people will find the study's results surprising. He continues:

"Having separately measured stocks and flows of trade, capital, information and people since 2005 for 140 countries representing 99 per cent of the world's GDP, in terms of its depth (size in relation to domestic activity) and breadth (international diversity), the study claims the world today is less connected than it was in 2007."

Bowman enhanced his article with a chart provided by DHL that shows the Connectivity Index "remains considerably lower than its 2007 peak." He continues:

"While the overall index has remained flat since 2009, depth and breadth of connectedness are moving in opposite directions, the former up and the latter down. This signals is the growing importance of a smaller number of exchange partners."

Of the three traditional flows associated with globalization (i.e., people, capital, and resources), the easiest to accomplish in the electronic age is the flow of capital. Bowman reports, however, that "declines in capital rather than trade flows are the real drag on global interconnectedness: information flows are trundling along a plateau, flows of people are up slightly, trade has rebounded strongly since 2009, but capital flows have continued to fall following the eurozone crisis – investors, the report says, are becoming a lot more selective about their foreign investments, leading to increased fragmentation of capital markets. As the report's authors point out, it's not just capital markets in which regionalisation is important:"

"While the depth of merchandise trade (the volume of goods traded in comparison to total economic output) has scaled new heights in recent decades, that trend has not been matched by an extension of the distances traveled by traded goods on average. Rather, much of the action in terms of trade integration has been the weaving together of national economies within the same region."

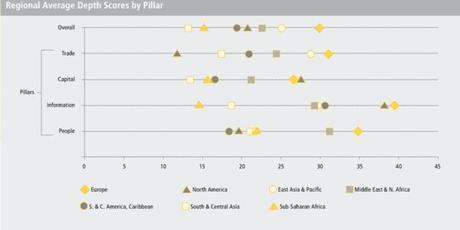

Bowman's article was accompanied by a graphic (shown below) that scores regions according to the depth of connectivity they enjoy.

Source: DHL

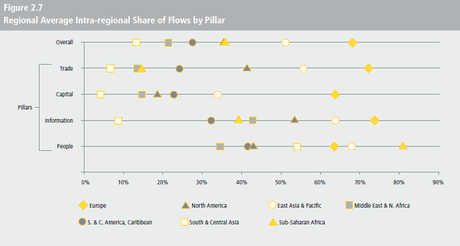

Source: DHL

The report concludes that Europe is the most connected region (with nine of the top ten most connected countries in 2011 being located there). "The Netherlands retained its 2010 position as the world's most connected country." ["World is less connected, says DHL," Supply Chain Standard, 29 November 2012] Bowman writes, "No surprises on the emerging markets front that sub Saharan Africa tends to lag and east Asia tends to lead." But the Supply Chain Standard article notes, "The countries with the largest increases in their global connectedness scores from 2010 to 2011 are Mozambique, Togo, Ghana, Guinea and Zambia – all of which are located in Sub-Saharan Africa. While this region remains the world’s least connected, it averaged the largest connectedness increases from 2010 to 2011." Bowman continues:

"Things get more interesting when comparing regional average depth of flows in the chart above to the intra-regional share of flows in the chart below – this shows a relatively good association in terms of ranking between regional scores on depth and intra-regional flows. The implication is, as the report puts it, that 'regional integration has been an essential part of rather than an alternative to global integration.' While Asia's export success is generally viewed in terms of its ability to export manufactured goods to the west, its regional supply chains have been also been crucial to the development of its manufacturing base."

Source: DHL

The study only confirms what I have stated about regionalization in the past: it is taking place within the overall framework of globalization rather than being seen as an alternative to it. Bowman concludes, "This message is particularly important for sub-Saharan Africa as it seeks to improve its position in the rankings." It is a message that Africans have apparently heard because Bowman reports that there is "some cause for optimism here." The optimism arises from the fact that "intra-regional trade negotiations have been proliferating across sub-Saharan Africa in recent years." Bowman goes on to note that efforts to create a stronger economic region in Africa have stalled. The report, however, notes that it is not the diplomatic efforts that creating the greatest barriers to further African integration, it's lack of infrastructure.

"The challenge of weaving this region closer together ... is exacerbated by the fact that much of its physical infrastructure was designed by former colonial powers with the aim to efficiently ship resources out of Africa rather than to facilitate intra-regional trade. And more basic infrastructure improvements could also have large impacts: by one estimate, if all the interstate roads in West Africa were paved, that might as much as triple trade within that subregion."

Clearly regionalization is going to remain a prominent (if not increasing) feature of tomorrow's business landscape. Commenting on the study, Frank Appel, CEO Deutsche Post DHL, stated, "Especially in this period of slow growth, it's important to remember the tremendous gains that globalisation has brought to the world's citizens and to recognise it as an engine of economic progress. Above all, governments must resist protectionist measures that hinder cross-border interactions." Professor Ghemawat stated, "The benefits of expanding merchandise trade are much larger than traditional models indicate. Adding to that the gains from services trade and other kinds of cross-border flows, the estimated economic benefits double to at least 8 per cent of global GDP."

The Supply Chain Standard article concluded, "The report highlights evidence that the depth of global connectedness – the proportion of flows that cross national borders – contributes to economic development and prosperity." In other words, globalization (even with increased regionalization) remains critical to the success of the global economy.