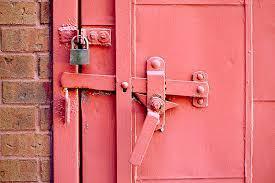

My friend Olga arrived here as a Soviet Jewish refugee in 1979; I’ve written about her. She got out just before the door slammed shut. The USSR was one big prison, especially for Jews, victims of severe discrimination.

My friend Olga arrived here as a Soviet Jewish refugee in 1979; I’ve written about her. She got out just before the door slammed shut. The USSR was one big prison, especially for Jews, victims of severe discrimination.

My humanist group recently viewed a wonderful film about them, Stateless, mostly interview footage with refugees now in America, relating their stories. Seeing it was an emotional experience.

The plight of Soviet Jews became a big issue in the ’80s. When Gorbachev met with Reagan in Washington, large demonstrations demanded that Soviet Jews be let go. Reagan pressed Gorbachev on the issue (this was back when U.S. presidents still stood for what was right).

And the doors flew open.

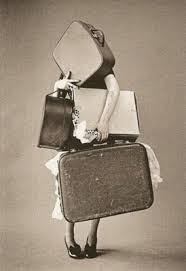

Meantime, the local police would know who was scheduled to leave; they’d break into apartments to steal the packed bags.

One woman said that when she’d handed over the final bribe, with almost her last rouble, she actually felt elated: a price worth paying to escape that prison.

The refugees traveled to Vienna, then to Italy, to await final transit to either Israel or America. Actually having a choice was an intoxicating novelty. That was one shock upon reaching the West.

People from government and aid agencies met them to help. But they viewed these offers with suspicion; the idea of such assistance seemed alien and implausible. Especially with no bribes even demanded! But on the streets, smiling cheerful people were another surprise. How unlike Moscow. So this was what freedom looked like.

Those opting for America needed refugee visas from consular officials who interviewed them to document their histories of persecution. This was hard; what they’d endured had been so internalized, so integral to seemingly normal life, they didn’t realize there was anything to report. While some, on the other hand, flagrantly embellished. (Lying was also the Soviet normal.)

The issue came to the attention of Congress (this was back when it could still actually legislate to solve a problem). Senator Frank Lautenberg (D-NJ) introduced a bill relieving Soviet Jewish refugees from having to individually prove persecution. The bill swiftly passed.

And the doors flew open.

Hearing these people’s stories made me love it that they’re now my fellow Americans. Anyone with the grit to go through what they did to get here, I want here. This is what America means. This is what made it great.

* I remembered my own Sheremetyevo experience. “Numismatic tours” of Russia in 1993 and 1995, led by Erastus Corning Jr., were a fantastic buying opportunity — on the second trip I bought 92 pounds of coins.

I met up with the others. Erastus said, “Give Misha $100.” I instantly understood, and handed over the money, saying “Wasn’t Misha taking a big risk?”

“Misha knows what he’s doing,” Erastus replied. “He was with the KGB.”

Advertisements