What do you do when you have a still functional film genre based around a sport whose appeal and popularity have fallen off pretty dramatically over the last fifteen years? The sport, it should be noted, is boxing, that sweetest of sciences that has played to many moviegoers’ love of individualism, machismo, and violence for more than a century. As a popular sport, however, boxing may be at the lowest cultural ebb that it’s ever been, and it seems likely to continue downward into the niche. Quickly…who’s the World Heavyweight Champion? (To be honest, I’d have to Google it, too.) If nothing else, Real Steel devises a viably high concept, if not especially creative, idea for addressing its problem, and one that plays well into the modern lust for CGI action. The idea that can be summed in three words: big battling robots. And with that, everything old feels new again…or at least, newly repackaged.

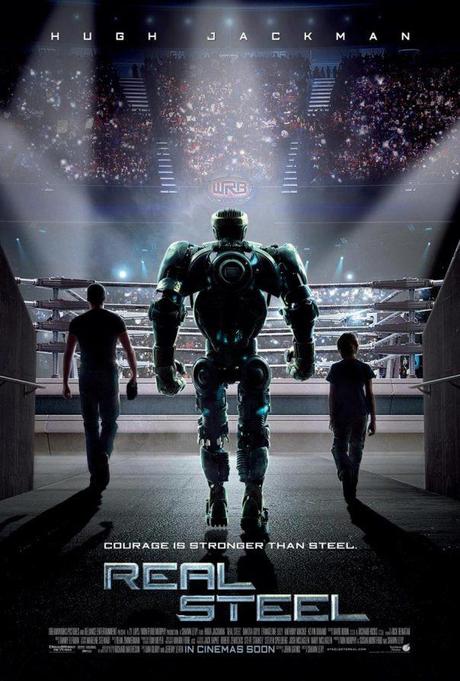

Though set in 2027, with few changes Real Steel could have easily taken place during the Great Depression. Charlie Kenton (Hugh Jackman), a washed up ex-boxer, drives the country back roads, lives out of his truck, and takes fights wherever he can get them, all the while drinking too much and gambling away money he doesn’t have. The only difference from the old carnival boxer cliché is that Kenton isn’t the one doing the fighting, instead using a battle-scarred old robot that looks sorrier than he does, though not by much. Robots, Charlie explains later on, replaced the real fighters years earlier when combat styles got more complex and the audience’s thirst for carnage grew beyond reasonable expectations (which doesn’t sound especially plausible, but I guess it’s a less depressing reason than “the concussion crisis”). Unfortunately for Charlie, he’s an inept hustler badly in debt to a lot of the wrong people when his robot finally takes one hit too many. Informed shortly thereafter that his ex-girlfriend has died, leaving the eleven-year old son Charlie’s been ignoring for over a decade more or less orphaned, he sees a money-making opportunity, essentially selling the boy’s guardianship to his ex’s sister and brother-in-law so he can buy himself a new robot. The only hitch is that he has to first take care of the boy, Max (Dakota Goyo), for the entire summer. Inevitably, the gruff loner and the son bond over their mutual passion for robot boxing, especially when Max discovers a diamond in the rough (or specifically, the junkyard) called Atom – an antiquated sparring robot whose unique operating system and ability to take punishment makes him ideally suited to turn around Charlie’s fortunes.

As said, outside of the futuristic robots and cell phones, Real Steel could just have easily been set in 1930s rather than the 2020s (though if the film is a prelude of things to come – 3D televisions will not catch on). Calling back to films like The Champ and The Golden Boy, and even Cinderella Man, the film is awash in the tropes and clichés of the old-fashioned boxing film, telling its father-son story against the age-old narrative of the scrappy underdog climbing the mountain from back alley brawls to major arenas and all the way up to the title fight in front of a worldwide audience. Though the plot for Real Steel sometimes feels more mechanical than its robots, it’s watchable enough, if wholly unoriginal. And as for those fighting robots (created through a combination of CGI and stop motion), they’re remarkably believable when they’re interacting with the human characters. The fight scenes, however, are involving but not exemplary; there’s just something about robots doing the fighting instead of people that makes the action fell less visceral and low risk than if it were people clashing instead, which is probably why in real life human fighting will still be around for another few thousand years, at least. The main robot, Atom, is visually appealing – basically looking like a life-sized “Rock’em Sock’em Robot” – but he (if it should be called a he) exists as something of blank slate, and we’re never sure whether he actually has a mind of his own or if he’s just an inanimate object. Despite that, strangely enough, some of the film’s best moments are when it’s onscreen and playing off of the human characters, who strangely seem more authentic playing off a robot than each other. The actual acting for those human characters is serviceable. Jackman plays testosterone-drenched sensitivity well, though he doesn’t always find the right balance between a potentially loving father and a genuine scumbag. Evangeline Lilly makes the best of being his long suffering, sometime girlfriend, and Goyo does fine work as his son, despite being fairly Gibberish. Everyone else is basically playing their type and stereotype, another thing that makes Real Steel seem less-than-superficially old-fashioned.

For a film about giant, boxing robots, Real Steel is generally as entertaining and compelling as you would reasonably expect it to be, but it’s far from a knockout. Part of the problem, of course, is that the premise is inherently silly, and therefore it’s hard to take any of the attempted emotional moments all too seriously. The climactic fight, however, will draw you in, even if its final outcome bears perhaps too much of a similarity to another, truly classic boxing film. Real Steel itself isn’t a classic boxing film, though it gets its formula more or less right. In the end, that should be good enough for a TKO. Or at least a rental.