Those familiar with maritime lore will certainly recall the Raifuku Maru, one of the more colorful victims of the Bermuda Triangle. While carrying a cargo of grain from Boston to Hamburg in April 1925, the Japanese freighter flashed a desperate, baffling SOS message: "Danger like dagger now! Come quick!" Ships tried locating the vessel but it disappeared without a trace. Cue speculation from generations of writers wondering whether the dagger was a waterspout, a UFO, a kaiju beast, or some other product of the excitable Asian mind.

Those familiar with maritime lore will certainly recall the Raifuku Maru, one of the more colorful victims of the Bermuda Triangle. While carrying a cargo of grain from Boston to Hamburg in April 1925, the Japanese freighter flashed a desperate, baffling SOS message: "Danger like dagger now! Come quick!" Ships tried locating the vessel but it disappeared without a trace. Cue speculation from generations of writers wondering whether the dagger was a waterspout, a UFO, a kaiju beast, or some other product of the excitable Asian mind. Unfortunately, it's easy to prove this story is bunk. Leaving aside that its route took it nowhere near the Bermuda Triangle, it was a banal, though tragic incident. All Lawrence D. Kusche, author of The Bermuda Triangle Mystery - Solved, needed to debunk this story was to crack open a Lloyd's of London reference book, Dictionary of Disasters at Sea, which shows that the Raifuku Maru sank with all hands in a storm, in the presence of the White Star liner RMS Homeric. No mysterious message about a dagger, either: the log read that the Japanese wireless man sent the ungrammatical, but understandable message "Now very danger!"

Case closed, then. No UFOs or daggers, no Japanese radio operator babbling like a poorly-dubbed Godzilla victim, no "mysterious disappearance." The only mystery is how such a commonplace tragedy became "mysterious" in the first place. This article tries to chart that journey from history to myth.

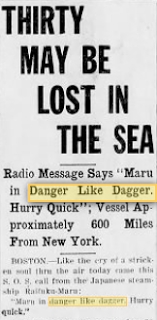

When the Raifuku Maru sank on April 21st, 1925, it became front page news across the world. The two main sources for subsequent reports were the Associated Press (AP) and the United Press International (UPI). Reading their separate accounts of the incident is extremely revealing: where the UPI's account is relatively sober, relying on official documents and eyewitness testimony, the AP's version (in its language, anyway) seems largely the work of an excitable, imaginative reporter.

The opening line reads with breathless excitement: "Like the cry of a stricken soul thru the air today came the SOS call from the Japanese steamship the Raifuku Maru: 'Maru in danger like dagger. Come quick." That said, the rest of the article seems respectable enough: the AP author recounts the desperate efforts of numerous vessels to find and rescue the Maru, revealing a much more complex story than the Triangle account would have it.

Postcard displaying the RMS Homeric

At least four vessels responded the Maru's SOS calls. The first was the President Adams, an American steamship who communicated with the stricken vessel, assuring the Maru that it was on its way. This appears to be the only successful contact with the Japanese ship, as subsequent attempts by the Adams, Homeric and other vessels to ascertain the Maru's position met without response. As the Homeric was closest to the Maru's assumed location, it was the only vessel to reach the scene.Even so, the Maru's operator, Masao Hitawari, continued sending updates to his would-be rescuers. He commented that the ship was encountering ferocious winds, that the vessel was beginning to list to starboard and that a lifeboat had been smashed. Then came the "Now very danger!" comment recorded in the official log. Hitawari's last recorded comment attempted to reassure his rescuers that the situation appeared to be improving: "No wind anger, but coming lifeboat from 60 miles there."

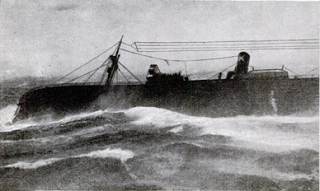

The Homeric, captained by John Roberts, a longtime White Star veteran, arrived on the scene in time to witness the Maru foundering. Its 38 crewmembers were gathered on the bridge, clearly visible in photographs of the incident. With the storm raging, Roberts made an effort to reached the doomed vessel, even lowering three lifeboats into the water. He soon, however, decided to recall them. Besides the weather, Roberts had over 900 passengers onboard and preferred not to risk their lives.

So the Maru sank into the abyss, taking its crew with it. The Homeric and another vessel, the Greek liner King Alexander, scoured the sea for lifeboats or survivors, but the inclement weather prevented any rescue. The Alexander lost a lifeboat and suffered serious damage to her windows and ventilators from gales before turning back. The Homeric's Captain Roberts was obliged to send a tragic message to the Camperdown radio station: "OBSERVED STEAMER RAIFUKU MARU SINK IN LAT 4143N LONG 6139W REGRET UNABLE TO SAVE ANY LIVES."

The Raifuku Maru photographed while sinking, its crew visible on deck. (source)

The incident soon degenerated into scandal and controversy. A number of Homeric passengers accused Captain Roberts of not trying to rescue the Maru's crew. One such accuser was Amos Pinchot, brother of Pennsylvania Governor Gifford Pinchot, who published a six column broadside in the New York Times. “I personally saw several men in the water, either swimming or being carried by the current,” he claimed. “It is hard to see how [Roberts] could have done less to save them.” Other passengers echoed Pinchot's sentiments.Roberts defended himself by commenting that “I was busy on the bridge maneuvering my ship and I did not spend as much time looking at the freighter probably as some of the passengers.” One hundred twenty other passengers signed a statement defending the Captain, and the Raifuku Maru's owners, the Kokusai Kisen Limited, publicly thanked Roberts for his efforts.

This did little to assuage the furor, especially in Japan, where the press cried racism. The Raifuku Maru, with its hull laid down in 34 days and launched in only 23 more (then a world record) upon its construction in 1918, had been the pride of Japan's merchant fleet and its loss was bitterly felt. Only the intervention of Emperor Taisho, who urged forgiveness while allotting 310 yen pensions to the family of lost crewmembers, cooled the argument.

Since the United Press International account is more sober, one wonders where the "dagger" comment originated from. Perhaps it came from a crewmember on the Homeric or another vessel who misremembered the message; perhaps it was simply the imaginative phrasing of an AP reporter. Even so, the original report makes no suggestion of a "mystery," and its thorough recounting of the incident belies its oft-purple prose.

Source

Less charitably, the "dagger" comment also plays to Oriental stereotypes, implying that Hitawari would rather baffle gaijin with aphorisms than send a clear message for help. Later accounts built upon this, criticizing the radio operator's "schoolboy English" as if he were to blame for the disaster. An editorial published in the National Association of Manufacturers even mused about the "little wireless man [who] knew that, by the invention of the civilized man, he could summon aid from out [sic] the mysterious depths."The AP account isn't credited, but it likely originated from John B. Knox, who spent forty years as the AP correspondent and editor for Boston. Knox periodically wrote about the Raifuku Maru up until his retirement in 1964, all repeating the "Danger like dagger" comment. The sinking was so associated with Knox that his obituary in November 1970 even mentioned it. Knox's colleague, Boston Globe crime writer Joseph F. Dinneen, included a fictionalized account of the sinking in his 1958 novel, Queen Midas.

As the incident receded into memory, the "Dagger" quote lingered on. The first report I found labeling the Maru as a "mystery" came in February 1939, nearly fourteen years after the sinking. A report of a strange SOS call, indicating that a vessel had been "torpedoed" (it was the liner Bretagne, which was actually sunk by a mine), inspired the author to muse on past oceanic mysteries, such as the Mary Celeste and the "Nipponese steamer which some years ago radioed in Japanese schoolboy English before she vanished with her crew: 'Danger like dagger.'"

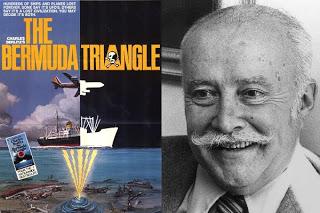

Suddenly mystified, the Maru drifted into the "Limbo of the Lost." In March 1958, an article published for the 40th anniversary of the USS Cyclops disappearance again labeled the Raifuku Maru an unsolved disappearance. From there it was a short step to the Bermuda Triangle, with writers Charles Berlitz and Richard Winer incorporating the suddenly-"mysterious" incident into their works (The Bermuda Triangle and The Devil's Triangle, respectively). These writers had no excuse not to cull from extensive official and newspaper records, except that they were more interested in selling books than recounting facts.

Charles Berlitz and his book (source)

It's obvious that picturesque description of a "dagger" from the early AP accounts appealed more than the sinking. Never mind that Knox, their probable author, didn't imply anything "mysterious" about the Maru tragedy; or that, even if the "dagger" comment were accurate, it was part of a longer wireless exchange involving several vessels, rather than a single confusing declaration. Divorced from context, and sprinkled with mystery-mongering and condescension, it becomes a whammo line that less implies a panicked crewmember stumbling over English than an inscrutable Oriental describing an unworldly terror.You would think that Kusche's book, or a simple Google search, would dispel this myth, yet the Raifuku Maru contains to sail the pages of credulous mystery books and wild-eyed websites decades after the Bermuda Triangle receded into half-remembered, embarrassing fad. Some folks truly prefer a colorful mystery to an ordinary disaster, facts be damned.

Note: This article drew heavily upon two online sources: Jay Sivell's article on his excellent blog, Lost at Sea, and a selection from Spurgeon G. Roscoe's "Radio Stations Common? Not This Kind" manuscript, online here. I used Newspapers.com and Google Newspapers to trace the story's evolution from history to mystery.