It’s often said that Hollywood has a fixation on youth, and this hardly a new trend. Throughout the entire history of American cinema, there have consistently been actors and actresses who shoot to superstardom for being the personification of youth.

As time moves progresses, so does the image of youth. During the 1910s, Mary Pickford was one of the most famous women in the world, celebrated for playing little girls in movies like Poor Little Rich Girl and The Little Princess. Although Pickford was well into her twenties at the time, the spirit and charisma she brought to those young characters won over audiences all over the world. Her long, curled hair became a symbol of the wholesome innocence of her characters.

By the early 1920s, things were beginning to change. After the end of World War I, many young women, known as flappers, were turning their backs on more conservative values by wearing dresses with higher hemlines, smoking, drinking, listening to jazz, going out dancing, working, dating, and generally having a whole lot of fun. Flappers also famously wore short bobbed hair styles; the antithesis of Mary Pickford’s long curls.

It was only a matter of time before Hollywood started capitalizing on this shift in youth culture. 1920’s The Flapper, starring Olive Thomas, was the first movie to focus on flappers and eventually, actresses like Clara Bow, Louise Brooks, and Joan Crawford would also become icons for playing characters that embody the lifestyle. But before all of them, there was Colleen Moore in 1923’s Flaming Youth.

It was only a matter of time before Hollywood started capitalizing on this shift in youth culture. 1920’s The Flapper, starring Olive Thomas, was the first movie to focus on flappers and eventually, actresses like Clara Bow, Louise Brooks, and Joan Crawford would also become icons for playing characters that embody the lifestyle. But before all of them, there was Colleen Moore in 1923’s Flaming Youth.

Flaming Youth was based on the novel of the same name by Samuel Hopkins Adams, also published in 1923. The novel quickly caused an uproar over its uncensored, sexually frank take on the flapper lifestyle and the lives of young women. By the time he wrote Flaming Youth, Adams had already built up a reputation as a journalist and novelist and didn’t want the salacious content of Flaming Youth to overshadow his other works, so he published it under the pseudonym Warner Fabian. (The Harvey Girls, The Gorgeous Hussy, and It Happened One Night were also based on works written by Adams.) The book caused such a stir that F. Scott Fitzgerald once wrote a letter to Adams saying that he wished he had been the one to write Flaming Youth.

As is the case with so many book-to-film adaptations, Flaming Youth isn’t completely faithful to its source material, but that didn’t stop it from being a worldwide smash upon its release. Colleen Moore stars as Patricia Fentriss, a young woman whose mother passes away after her hard-partying life catches up with her. Her mother hopes Patricia will go down a different path in life, but Patricia becomes a flapper and enjoys the wild life that comes with it. Like many flappers, Patricia is also not a fan of the idea of getting married. So when she meets Cary Scott (Milton Sills), her mother’s former boyfriend, she falls in love with him, but moves on to having an affair with a violinist when Cary leaves for Europe. However, that fling comes to an end after she and the violinist get into a fight during a party on a yacht, which ends with her jumping overboard to escape. After being rescued, Patricia is nursed back to health by Cary and changes her mind about marriage.

F. Scott Fitzgerald said of Flaming Youth, “I was the spark that lit up Flaming Youth, Colleen Moore was the torch.” Colleen Moore was already an established star in 1923, but Flaming Youth brought her to a new level of stardom. Her sleek, black bobbed haircut and bangs remain a definitive part of the flapper image.

The film was a big box office success, which comes as no surprise given the controversial nature of the book and the fact that the movie’s promotional materials played up its scandalous content. One lobby card described the movie as, “A spicy society exposé so startling that the author dared not sign his right name,” and promised to give, “…the bald facts, the truth about our modern society with its gay life, its petting parties, its flapper dances, its jazz.” Another lobby card asked, “How far can a girl go?”, and elaborated, “She smoked cigarettes. She drank. She went to petting parties. She led the pace of the gayest life in the gayest society.”

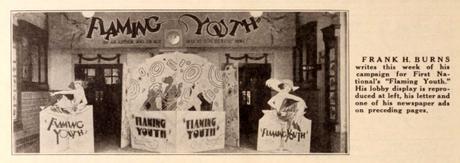

Theater lobby display promoting Flaming Youth

With hype like that, it’s hard not to be intrigued by it. At one point, the film was even banned in Canada and a theater owner was fined $5 for showing the film. In fact, The Exhibitor’s Trade Review advised theater owners in their December 1923 issue to exploit the film’s controversy:

“The best way to arouse the interest of the curious is to condemn the picture. There is here a peculiar psychology which makes people impatient to see what they have been told not to. Here is your cue for exploitation. Get out letters warning the people that the picture is rife with bold situations and un-restained necking parties and advise them not to see it and forbid their children to do likewise. They will come hotfooting it to your theater.

Inflame the minister with the outrages against society on the part of the younger generation, and get him to preach a sermon on the subject using the picture to illustrate his point.”

Reviews from the era generally paint it as being an enjoyable movie. The Exhibitor’s Trade Review said of it, “What makes this picture different, is not its subject matter, but the manner in which the story is handled by a competent cast. It is the same old tale of the jazz crazy modern age, chock full of picturesque scenes and amusing situations.”

While Colleen Moore certainly got the most attention for her role, Milton Sills and Myrtle Stedman (who played Patricia’s mother) also got good notes from the New York Times. Many of the less favorable reviews point out that it isn’t a completely faithful adaption of the book. One reviewer from the Cincinnati Inquirer didn’t care for any of the characters and wrote, “Throughout the production, scarcely a single admirable character appears, and the audience is regaled with the antics of a lot of childish adults and adulterated children. Consequently, the members of the cast, though many of them are talented, work against unfair handicaps.”

Despite the fact that Colleen Moore was such a big hit in Flaming Youth, she didn’t stick to flapper roles for much longer. The following year, she starred in The Perfect Flapper, but it wasn’t as well received. By that time, other actresses had also made a name for themselves for playing flappers, particularly Clara Bow, so Moore simply moved on with her career. Although she publicly declared that she was done with flapper pictures, Moore would go on to star in 1929’s Why Be Good, in which she plays a young, modern, forward-thinking woman.

The flapper type fell out of popularity in American culture around the time of the stock market crash of 1929 when their lifestyle was suddenly deemed frivolous. In the 1930s, there was a return to a more wholesome image of youth in cinema, with stars like Shirley Temple, Mickey Rooney, and Judy Garland becoming some of the top box office draws. It wouldn’t be until the mid-to-late 1950s and early 1960s that we got to see the more adult side of youth again in movies like Rebel Without a Cause, Peyton Place, Splendor in the Grass, and A Summer Place.

Flaming Youth is a prime example of how a movie being a major success upon its release doesn’t necessarily guarantee preservation. While many of the definitive flapper flicks of the 1920s, such as Clara Bow’s It and Joan Crawford’s Our Dancing Daughters, still exist and are very easy to see, Flaming Youth is now a partially lost film. Originally, Flaming Youth had a runtime of 90 minutes, but only about 10 minutes worth of footage is known to still exist.

The few minutes that remain are fascinating for a multitude of reasons. If you’re a fan of 1920s fashion and beauty, you’re going to love the footage of Patricia getting dolled up for a party. An infamous skinny dipping sequence during a wild party, shown in silhouette, is among the existing footage and is a perfect example of how director John Francis Dillon used artistic vision as a way to sidestep censorship, something which was pointed out in many reviews from 1923. But most importantly, it’s still easy to see why Colleen Moore was such a delight to audiences.

Unfortunately, Flaming Youth isn’t the only Colleen Moore to become lost over time. Despite being one of the biggest stars of the 1920s, only about half of her films are still known to exist in a complete state. But it’s certainly not due to a lack of effort on Moore’s part. She personally gave prints of her films to the Museum of Modern Art, but due to an administrative oversight, they weren’t properly cared for. Years later, she contacted MOMA to check on the condition of her films and learned they had deteriorated too badly for them to be saved. Despite all of her efforts to find other prints of her films, she had little luck. Perhaps one day, a complete print will be found somewhere and the world will be able to see Colleen Moore at her peak once again.

Advertisements