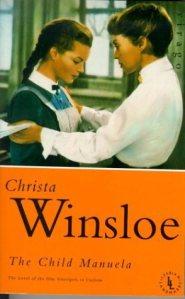

German novelist and playwright Christa Winsloe wrote a daring book for her time: The Child Manuela, published in 1934; a novel about a young lesbian’s love for an older woman. It was first published as a play, and later adapted into two movies: Madchen (Girls) In Uniform in 1931 and the 1958 remake of the same name.

In the novel, set in 1910s Prussia, young Manuela von Meinhardis is born to a respected officer in the Prussian regiment, and to a loving mother. The story starts out with Manuela’s carefree childhood, until the deaths of her oldest brother Ali and her mother. Throughout the story, Manuela’s lesbianism is hinted. Her first love starts as a child, with a self-centered classmate, Eva, who just wants to use Manuela to get Manuela’s other brother, Berti. As the girl enters her teens, she is courted by Fritz, but falls madly in love with his mother. Manuela’s father, mistakenly believing his daughter loves Fritz, sends her to a stringent boarding school for officer’s daughters.

Once at the school, Manuela is overwhelmed with the regulations and the stern, unsympathetic staff. Only one teacher, Elisabeth von Bernburg, shows friendship and compassion for the girls. Manuela welcomes the attention, and finds herself falling in love again, but deeper, with Fraulein von Bernburg. Though the teacher herself has feelings for Manuela, she is reserved and aloof. At the headmistress’s birthday party, Manuela gets drunk and yells of her love for Bernburg, leading to the headmistress’s wrath and isolating punishment. Fraulein von Bernburg is dismissed, and Manuela, feeling alone and abandoned, makes a tragic and irreversible decision.

Having seen the 1958 movie based off of this book, I was really excited to read the original version. Sadly I was disappointed. First, though The Child Manuela is a “lesbian classic”, the story takes a long time to get into that genre. The plot dragged on with Manuela as a very young girl. Though the book is told in multiple viewpoints, I found it sometimes cut into Manuela’s view. And a lot of the scenes, though devoted to describing Prussia in that time period, seemed unnecessary to Manuela’s story. I found myself wondering when the book would pick up.

As the novel slowly goes into Manuela and her growing sexual feelings for women, it gets a bit more interesting. Still, the dialog between characters was often slow, or not very believable. Manuela’s crush on Eva seemed tacked in, and not a real romantic feeling.

The Child Manuela has interesting characters, like Ilse, the funny, rules-optional pupil at the boarding school, Edelgard, Manuela’s kind and understanding friend, and Manuela’s father, known only as Meinhardis. They all give their own quirks to the novel, and there were some moments that were funny, such as Manuela’s conversations with Ilse. Still, the viewpoints of some characters broke into Manuela’s story, which took away something from the plot.

Winsloe did do a good job showing the homophobia at that time, when the school learned of Manuela’s attraction. The self-righteous attitude, the need to “cure” Manuela, and the belief of her sexuality being “abnormal.” The poor young girl is put in isolation, away from her friends, and is viewed as something bad by the headmistress. Even Bernburg tells her that her love is wrong. All this builds up to the story’s tragic conclusion.

What bothered me most about this book is, of course, the ending. For a young teen girl coming out to herself and her family, I would definitely not recommend this novel. What happened to Manuela is very sad and depressing. The movies had a happier conclusion for her than the book did. At least in the movies there is hope for Manuela. But the book left no room for hope. It was horribly sad to read about, and in a way grow up with, this young girl, and have her story end so tragically. Another downer for the ending was that it just ended in an abrupt manner that was almost rude. The story flowed, then the tragic event happened, and the story just stopped. There was no aftermath of what happened to Fraulein von Bernburg or Manuela’s friends. There was no answer to the question of whether the headmistress would change her awful policies. The story just stopped with no time for what had happened to truly sink in; no conclusion. After the story is just a “The End”, which dashed all hopes for a better outcome, or at least something to make the book worthwhile.

I’m extremely fond of the 1958 Madchen In Uniform, but The Child Manuela does not hold a candle to it. For readers looking for a story with a happy, or at least the hope of a happy ending, look elsewhere. You should only read it if you really love old lesbian fiction. I have no intention of reading this book again. It was a pure disappointment.