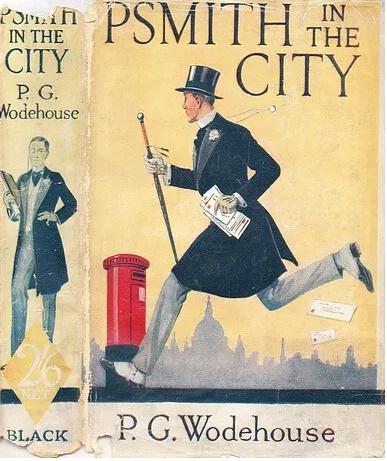

Book Review by George Simmers: Psmith in the City is maybe P.G. Wodehouse’s most autobiographical novel, in that he was in the same predicament as its hero. In 1900, at the age of nineteen, he learned that because his father’s pension was paid in rupees, and the rupee had collapsed, there was not enough money to send him to follow his brother Armine to Oxford, so he must find a job. Wodehouse went to the Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation (today better known as HSBC), where he spent an unhappy time, until he was earning enough from his sideline in comic writing to escape the world of banking..

I did not read the story in the 1910 edition, but as it had appeared first in 1908, in the Captain magazine, a publication for boys, with a large public school readership.

The Captain: A Magazine for Boys and Old Boys

The Captain: A Magazine for Boys and Old Boys

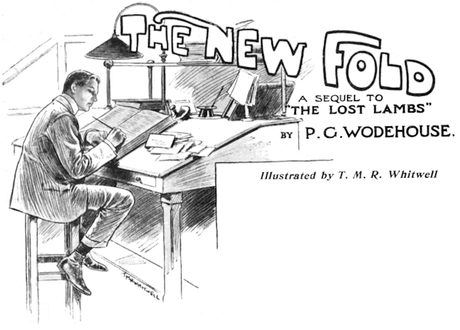

The serial’s title then was The New Fold, because it was a sequel to an earlier serial called The Lost Lambs, which had developed the characters of Mike Jackson, a promising cricketer, and Psmith, previously an Etonian, who had both been condemned, as a punishment, to spend their last school year at Sedleigh, a disappointingly minor public school.

In the first chapter of The New Fold, Mike is told that he cannot go to Cambridge, and like Wodehouse before him, is sent to work in a bank; He is unhappy:

“He had been used to an open-air life, and a life, in its way, of excitement. He gathered that he would not be free till five o’clock, and that on the following day he would come at ten and go at five, and the same every day, except Saturdays and Sundays, all the year round, with a ten days’ holiday. The monotony of the prospect appalled him.

For Mike the bank duplicates the worst aspects of school – work that is uninteresting and seems arbitrary, and superiors who are dull and unsympathetic. The manager of the bank, Mr Bickersdyke, is a man of such dismal character that when we first meet him he is waking behind the bowler’s arm just as Mike would otherwise have been set to make a century. The bank brings out the worst in Mike, making him morose and petulant.

The monotony of life in the bank, however, is broken by the sudden appearance of his friend Psmith, whose father wants him to go into commerce, and therefore has found himself a job in the same bank as Mike.

Psmith’s attitude is completely different from MIke’s; contemplating the prospect of work, he says:

‘I shall toil with all the accumulated energy of one who, up till now, has only known what work is like from hearsay. Whose is that form sitting on the steps of the bank in the morning, waiting eagerly for the place to open? It is the form of Psmith, the Worker. Whose is that haggard, drawn face which bends over a ledger long after the other toilers have sped blithely westwards to dine at Lyons’ Popular Cafe? It is the face of Psmith, the Worker.’

Psmith is in many ways the opposite of Mike. Mike is essentially serious, and has many of the characteristics of Wodehouse himself as we meet him in biographies – he is a shy, unassuming man, and not very good with strangers. Psmith is consistently outgoing, verbose and the master of every situation. But maybe a better way of thinking about him is not as Mike’s opposite, but as his complement. Because Psmith is not just a fantasy figure, but the embodiment of the other side of Wodehouse, the side that emerged in his writings. He is a lord of language, using it to dominate every situation. Psmith constantly rises above every difficulty through his manner of speaking. He confuses those he is speaking to, especially his superiors at the bank, by his utter confidence. His tone is disconcertingly various; in a single speech he may mix registers of speech in ways that wrong-foot the listener, as he goes from newspaper speech to the language of melodramatic fiction, to phrases out of sanctimonious sermons. His listeners are confused, unsure whether they are being made fun of or patronised. Psmith triumphs because he refuses to take social hierarchies seriously. The fact that he typically calls everyone ‘Comrade’ is a joke about the absurdity of socialism, but Psmith’s instincts are democratic and wide-ranging:

One of the many things Mike could never understand in Psmith was his fondness for getting into atmospheres that were not his own. He would go out of his way to do this. Mike, like most boys of his age, was never really happy and at his ease except in the presence of those of his own years and class. Psmith, on the contrary, seemed to be bored by them, and infinitely preferred talking to somebody who lived in quite another world. Mike was not a snob. He simply had not the ability to be at his ease with people in another class from his own.

Psmith also has a ruthlessness lacking in Mike, who has absorbed the gentlemanly code of his class. Blackmail and charmingly phrased threats come as naturally to Psmith as cricket does to Mike.

Mike is angry and depressed at being condemned to life in a bank:

What’s the good of it all? You go and sweat all day at a desk, day after day, for about twopence a year. And when you’re about eighty-five, you retire. It isn’t living at all. It’s simply being a bally vegetable.

But Wodehouse, writing ten years after his own escape from banking, could write that Mike ‘was not old enough to know what a narcotic is Habit, and that one can become attached to and interested in the most unpromising jobs.’

If the bank replicates the worst aspects of school, it lacks the compensations that Wodehouse had found at Dulwich College, and it is in contrast to the cricketing joys of school that the bank is a deep disappointment. Still, he is forced to admit that the community there is not entirely unpleasant.

Whenever a number of people are working at the same thing, even though that thing is not perhaps what they would have chosen as an object in life, if left to themselves, there is bound to exist an atmosphere of good-fellowship; something akin to, though a hundred times weaker than, the public school spirit. Such a community lacks the main motive of the public school spirit, which is pride in the school and its achievements. Nobody can be proud of the achievements of a bank.

Even so, here are interesting men at the bank, and most seem to have an outside interest in which they can express the humanity that the bank squashes. One is obsessed by Socialist politics, and another by Association Football. One, briefly glimpsed, has a sideline which is perhaps a reference to Wodehouse’s own:

And there was Raymond who dabbled in journalism and was the author of ‘Straight Talks to Housewives’ in Trifles, under the pseudonym of ‘Lady Gussie’

Like Raymond, while working at the bank, Wodehouse also made his first steps into writing, contributing mostly short comic pieces to magazines and newspapers. After a while he was earning as much from this spare-time writing as from his bank job, and so he took it up full-time, progressing through comic articles to school stories to the comic novels for which he is famous. As a writer, if not as a bank clerk, he was a workaholic.

This novel is one that raises the question that intrigues me: if his father’s finances had not gone to pot, and he had gone to Oxford, would Wodehouse still have become a writer, and if so, would he have been a very different one if he had undergone a university education, rather than the hard training of journalism and the discipline of the popular fiction magazines?