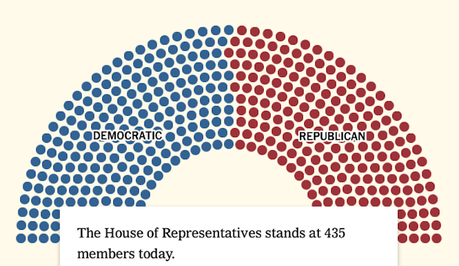

Jesse Wegman and Lee Drutman have written an article in The New York Times about our current divided and ineffective Congress. They suggest going to a system of proportional representation. Here is some of what they wrote:

As a new Congress sputters into gear, this rusty binary split — a product of our antiquated winner-take-all electoral mechanisms — is key to understanding why our national legislature has become the divisive, dysfunctional place it is today. It is why more than 200 leading political scientists and historians (including one of the authors of this essay) signed an open letter in 2022 calling on the House of Representatives to adopt proportional representation — an intuitive and widely used electoral system that ensures parties earn seats in proportion to how many people vote for them. The result is increased electoral competition and, ultimately, a broader range of political parties for voters to choose from.

In 2024 fewer than 10 percent of U.S. House races were competitive. In a vast majority of districts, one party or the other wins by landslides. Driven by a decades-long geographic sorting that has concentrated Democrats in cities and Republicans in rural areas and reinforced by partisan gerrymandering, this split electoral landscape has fostered a polarized climate that becomes more entrenched with each election.

The heart of the problem is the system of single-winner districts, which give 100 percent of representation to the candidate who earns the most votes and zero percent to everyone else. . . .

In less polarized political times, winner-take-all systems can do a decent job of reflecting public opinion and maintaining democratic stability, but when a nation is deeply divided and large numbers of people fear that they will not be represented at all, the result is an erosion of trust in government and rising extremism and political violence. As the political scientist Barbara F. Walter has observed, a majority of civil wars over the last century appear to have broken out in countries with winner-take-all systems.

No democracy can survive long in the face of this much division and distrust. It’s hardly surprising, then, that more than two-thirds of Americans want to see major changes in our political system. Roughly the same proportion wish they had more than two parties to choose from.

They’re right: Two parties competing in winner-take-all elections cannot reflect the diversity of 335 million Americans. . . .

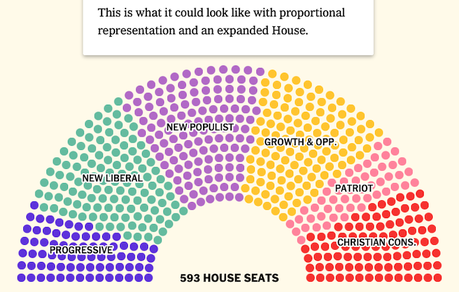

The switch from winner-take-all to proportional elections has been the most common major electoral system change among democracies in recent decades. Here’s how it would work in the United States:

Voters vote as they do today, but because districts have multiple members rather than single members, it allows several candidates to win seats without a majority of the votes. When the winning threshold goes down, the number of viable parties goes up. So multiple candidates from multiple parties can represent a district, giving millions more Americans the opportunity to vote for a winning candidate, whether that candidate is a Republican or a Democrat or a member of another party.What would that look like in 2025? How many parties would there be? To find out, we analyzed data from Nationscape, a large survey that polled hundreds of thousands of Americans on their political preferences. We used those answers to distribute voters among six hypothetical parties.

Offering Americans a choice among multiple parties doesn’t just give them a clearer voice in how and by whom they are governed; it also opens up possibilities for new political coalitions, which can in turn lead to the passage of broadly popular legislation. Our politics may seem intractable today, but on issues from gun control to immigration to education reform to A.I. regulation, winning coalitions are hiding in plain sight.

It also works better with bigger legislatures, but the U.S. House has been locked at its current size for more than a century. From the beginning of the House in 1789 until the early 20th century, its membership grew roughly in line with the U.S. population. At the start, there were about 34,000 constituents per representative; by 1911, that number had grown to more than 200,000 — much larger than the founders intended but still manageable. Today the average district holds more than 760,000 people, which is far too big for any one representative. As a result, tens of millions of Americans are represented by House members they did not support and in a highly polarized environment that leaves people feeling that they are not represented at all.

The fix for this problem is to expand the membership of the House of Representatives to reflect the size and diversity of the U.S. population in the 2020s rather than the 1920s. According to many political scientists, the optimal total number of members of the House and the Senate combined is equal to the cube root of the nation’s population. Legislatures in democracies around the world roughly align with this ratio; the U.S. House did, too, until its size was frozen by law at 435. Today the cube-root rule would give us a House with 593 members.

As a voter, you wouldn’t do anything substantially different from what you do now. You’d receive your ballot and pick the candidate you wanted to represent you in Washington. What would be different is that you would have more candidates and parties to choose from, and seats would be awarded in proportion to each party’s total vote share in a multiwinner district. The winners could be reported right away. No new voting machines or procedures would be required.

And the law could be changed to allow for proportional representation tomorrow.

Most of us, politicians and voters alike, have spent our whole lives in this broken system. But imaginations can expand, and conditions that seem unchangeable can change. They often do in a crisis like the one we are living in now. This is a rare moment of openness to reform, combined with and triggered by the dysfunction in American politics. We should seize it.