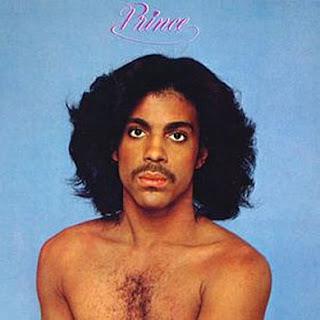

So much of Prince's eponymous sophomore effort can be summarized by its hysterical cover. Where For You functioned as primarily a disco record, Prince fit more into the funk mold. The move from a hot and current genre to the (relatively) old-fashioned sound that helped spawned it is matched by the change from For You's blurry, flashy cover to the almost-pastel colored photograph that adorns Prince. Featuring a visibly bored Prince standing with his shirt off, the album art suggests Prince at once in his own skin (figuratively stripped down from disco to funk and literally stripped down to a bare chest) and uncomfortably and artificially donning an image in the fierce hunt for success.

So much of Prince's eponymous sophomore effort can be summarized by its hysterical cover. Where For You functioned as primarily a disco record, Prince fit more into the funk mold. The move from a hot and current genre to the (relatively) old-fashioned sound that helped spawned it is matched by the change from For You's blurry, flashy cover to the almost-pastel colored photograph that adorns Prince. Featuring a visibly bored Prince standing with his shirt off, the album art suggests Prince at once in his own skin (figuratively stripped down from disco to funk and literally stripped down to a bare chest) and uncomfortably and artificially donning an image in the fierce hunt for success.That contradiction holds back Prince's second LP, but the fact that Prince is at least somewhat at home with the material marks a step up from his debut. It still sounds more like For You than Dirty Mind, but Prince shows its maker starting to consolidate his early sound into something more focused, capable of setting trends instead of merely following them. Hell, even as Prince starts to distance itself from disco, it does disco better than For You, managing to give even single-length numbers the elasticity and bounce of extended dance mixes and just having groove in the first place, an element sorely lacking from so much of the first album.

Prince opens with the extended cut of its lead single, "I Wanna Be Your Lover," instantly announcing the leap in quality and cohesion between this album and its predecessor. Adding a tighter low-end to For You's spacious synth lines, the track actually has a danceable beat to hook a crowd. Prince also develops his vocal style more, adding funkier, raunchier yowls to his slick falsetto that start to lay on the sex merely talked about in For You's more ribald tunes. "I Wanna Be Your Lover" proved to be a smash, climbing to the top of the Soul chart, going gold on its own and helping push the full LP to platinum status within months.

But it is not even remotely the highlight of the album. "Sexy Dancer" anticipates the compositional busyness that would make Prince's compositions among the densest pop ever recorded. With a female choir chanting the title over funky, spare guitar lines, programmed handclaps and drum patterns and humming synths, "Sexy Dancer" sounds more like a great b-side for Prince's next album than something from this era of his music. "Bambi," meanwhile, expands upon the rock-tinged For You closer "I'm Yours" with a much more refined guitar showcase that still makes an appearance live when Prince wants to cut loose with his axe. Best of all is "I Feel For You," which is not quite as Dirty Mind-ready as "Sexy Dancer" but is nevertheless the runaway highlight of the album. With giddy synths and a bassline that seems to pass through and back out of the song as if it were traveling in elliptical orbit around it, "I Feel For You" wouldn't fit in the arenas Prince would soon fill. But none of his songs to this point feel as primed to set a club going than this, even "I Wanna Be Your Lover," which clearly hooked listeners more.

As with For You, Prince suffers from an excess of uninspired filler. Generally, the fluff on this record rates higher than that of its predecessor: The half-rocking, half-funky "Why You Wanna Treat Me So Bad?" and swooning "Still Waiting" are solid numbers that simply do not stand out the way that the superior tracks do. "With You" and "It's Gonna Be Lonely," on the other hand, start slipping from memory even before they conclude. Both recall those weighted standing punching bags that always seem about to tumble, only to frustratingly whip back to their starting point unaltered. Even they seem like early classics, however, when stacked against "When We're Dancing Close and Slow." Easily the worst song off Prince's first two albums (and several LPs beyond that), this travesty lives up to its title by listlessly trudging through its approximation of a prom night slow dance. In fact, it so captures the awkward maneuvering and desperately repressed hormones of a teenage dance that the song may actually be a brilliant work of subjectivity.

But never mind the dross; Prince clearly develops from its artistically and commercially disappointing predecessor, and if it occasionally seems over-calculated to appeal to an audience, that planning clearly worked. In going platinum, the album helped conform Warner Bros' faith in the young artist when they signed him to a three-record deal. It must have also boosted Prince's confidence, as the man who mumbled nervously at the microphone of a rehearsal show for label executives would subsequently go out and support this album, proving so popular that he soon became Rick James' opening act. Before long, Prince and his assembled band would regularly sabotage James and win the open preference of the attending audience. That is more rebellious than anything on Prince, but Prince's music would soon match this brashness, and more.