Matthew Desmond previously wrote about our housing crisis in Evicted. His 2023 book, Poverty By America, is a broader examination of socio-economic dysfunction. Life for the poor is harder than it needs to be. And America has more poverty than it needs to, compared with other rich advanced nations.

It’s not as though we can’t afford to do better. In fact our “social spending” is very great — but most actually goes to the more affluent. (Of course there’s a reason. They have more votes.)

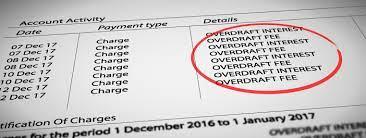

James Baldwin sixty years ago said it’s expensive to be poor in America. Desmond shows many ways the poor are milked. Bank profits, for example, rely heavily on stiff overdraft fees and the like, to which financially strapped poorer people disproportionately fall subject. They’re also often driven to “payday loans,” which Desmond particularly pillories. Translating a week’s loan fee into an annual percentage rate may sound exorbitant. Payday lenders actually provide a much needed service to their customers, and critics tend to overlook their costs of doing business. Yet needing such costly loans does make poverty expensive.

So does the criminal justice system, wherein small infractions can metastasize into crushing cost burdens, especially where people are charged for the privilege of being prosecuted and even incarcerated. Yes, that’s really a thing. When they fall behind in paying, fees build upon fees. Parents unable to pay can even have children taken away. (Desmond doesn’t discuss the human catastrophe of the whole foster care system.)

Thus, while he does give us some glimpses of what poverty is like, I felt there was not enough of that, in contrast to the vividness in Evicted — with poverty treated here more like an abstraction. The book’s tone and tenor is very preachy. We see little of the actual human beings affected. The subject could well have warranted more than just 189 pages.

A big part of the problem is segregation — not just by race but by economic class. Many factors banish poor people from better neighborhoods, like bad credit, a history of evictions, etc. Desmond at one point strangely pooh-poohs experimental programs giving poor families vouchers to move to upscale areas. But later he acknowledges that, even with no income increase, this “improves their lives tremendously” — exposure to crime drops, mental health improves, and children flourish in schools, with lifelong benefits. Desmond meantime laments the sociological harms from walling off the poor in ghettoes. “It brings out the worst in us, feeding our prejudices and spreading moral decay.”

It’s easy demonizing people you never meet. We’ve found that anti-immigrant prejudices melt away when people are exposed to actual migrants as part of their communities.

I’ve been a crank about education; whereas it could be a great equalizer, instead we perversely often subject poor and minority kids to substandard education that actually worsens the disadvantage they’re born into. But interestingly, Desmond points to Montgomery County, Maryland, which made a real effort to invest fully in schools in low income areas. Yet their students still did markedly worse than kids —even if equally poor — attending integrated schools. Integration proved more powerful than money.

Desmond argues that while affluent liberals are all in favor of integration, and public housing for poorer people, they don’t want it in their backyards. Another recent book, Bill McKibben’s The Flag, the Cross, and the Station Wagon, relates how in the ’70s all the good people in his suburban Massachusetts town endorsed a low-income housing project, but in the privacy of the voting booth overwhelmingly rejected it. A similar ethos underlies ubiquitous zoning restrictions making it hard to build anything anywhere, but especially housing geared to the less affluent.

The resulting shortage of such housing, combined with the mentioned factors keeping them out of better areas, limits their choices, which in turn enables “slumlords” to charge rents that can actually exceed those for nicer housing. Thus again making poverty expensive.

Desmond goes on to cite the “forced busing” for school integration, also mainly in the ’70s, as enormously consequential, because here, starkly, “working class white families were asked to bear the costs of integration in a way that white professionals never were.” Breeding “a festering resentment toward elites and their institutions” — universities, science, journalism, government — and “a new political alignment and a new politicized anger still very much with us today.” Indeed, still intensifying.

A basic theme of the book (implied by its title) is that we don’t merely tolerate a wide divide between the poor and the affluent, we like it that way. Moreover, Desmond contends that we are all actually culpable for the dire straits of our poor — that we benefit from it. He casts them as being exploited, with the rest of us as exploiters.

For example, he says that upscale consumers like to get stuff “fast and cheap” — “but somebody has to pay for it, and that somebody is the rag-and-bone American worker. Poverty wages allow rock bottom prices. Relentless supervision and control facilitate fast service.” So the “working class and working poor — and now, even the working homeless (my emphasis) — bear the costs of our appetites and amusements.”

This facile take conflates some very distinct economic phenomena. As if (turning inside out the usual indictment of capitalism) a business striving to give its customers low prices and good service is a bad thing! Of course, businesses do that because competition requires it. If they could charge more, they would. If prices are too high, or service sketchy, customers can go elsewhere, or even spend their money on different things altogether. That firm will fail. No boon for its employees.

Businesses do make profits. Some consider that evil ab initio. Though it’s the reason goods and services they love are made available at all. But are profits excessive? Sometimes, of course; but more generally competition drives them to a minimum. Most folks would be surprised to learn what few pennies of profit a typical business gets for every dollar of sales. The net profits of the entire U.S. airline industry, for the entire Twentieth Century, were approximately zero.

So — the real reason so many U.S. jobs pay so little is not “exploitation” as Desmond keeps saying. It’s because the goods and services workers produce are simply not worth more than they are, in the competitive marketplace. Just a fundamental reality.

It’s easy to suggest businesses should simply pay workers more and charge customers correspondingly more. But customers have a say in that. And indeed, if throughout the economy, wages were higher, and so in consequence were prices, we’d be where we started. Or else higher prices would mean consumers able to buy fewer things. That lessened demand for goods and services would reduce employment, making it even harder to earn a “living wage.”

Yet this is a very rich nation. What makes us rich is precisely that, compared to past epochs, we can produce so much, at so little cost to producers. It’s the basic reason why, notwithstanding the poverty Desmond depicts, far more of us can live very well indeed.

That’s economics. But the issue is also political, sociological, and ethical. Given the stubborn reality that a lot of people just cannot earn enough to live decently, what are we to do about it?

An issue advanced societies have wrestled with for centuries. “Are there no poor houses?” said Scrooge. Humanitarian instincts have long compelled us to do, well, something. But never coming to grips with the concept that all members of society should be entitled to basically decent necessities, just by being human. Instead we’ve built crazy-quilt patchworks of programs that nibble at the bullet without ever biting it.

And for all we’ve spent doing it, American poverty seems to remain intractable. Part of it is that, even regarding the small part of “welfare” actually targeting the poor rather than the rich, much of the money never actually reaches their hands. If we abolished all those programs and instead simply sent out checks, that would lift most people from the wretchedness Desmond castigates.

He does suggest this, more or less, calculating that as of 2020, the cost needed to have no American below the poverty line would be $177 billion (above what’s already spent on anti-poverty programs). In the big American picture, that’s actually chump change, practically a rounding error in the federal budget. Desmond says we throw away more in food annually.

Going further, he notes that a “Universal Basic Income” could cost $1 trillion or more annually. I might suggest, again, just sending everyone a check — yes, everyone. Taxes for the affluent majority would have to rise in consequence — cancelling out, for them, the benefit. But as you go down the income distribution, less affluent people, paying lower tax rates, would benefit more; the poorest most of all. While of course such a scheme would eliminate all eligibility issues and the kinds of massive administrative complexities that bedevil existing social programs.

A trillion is not exactly chump change. But meantime, Desmond also notes that unpaid taxes amount to about that much annually — which a better funded IRS (opposed by Republicans) could collect.

And he contends that we’d gain more from ending poverty than it would cost. Boiling it down, we’d be more free. Compared to the freedom wealth confers, “a freedom that comes from shared responsibility, shared purpose and gain, and shared abundance and commitment” is “a different sort of human liberation altogether: deeper, warmer, more lush.”

That verbiage may be over-the-top. But it’s true that such spending would buy vast human improvement. America would be a much better country. And people like Desmond could stop trying to make us all feel guilty.