In the past 24 hours, I’ve come across a curious concatenation of death obsessions. If I didn’t know better, I’d take it as a sign — an omen from nothingness.

The death stuff began with this review of Stephen Cave’s Immortality: The Quest to Live Forever and How It Drives Civilization (2012). Cave argues that “civilization is a major side effect of humanity’s attempts to live forever.” Setting aside for a moment the tenuous claim that the domestication of plants-animals was driven by a desire for immortality (rather than a survival desire for a reliable food supply), Cave identifies four immortality narratives (Staying Alive, Resurrection, Soul, and Legacy) that spur the further development of “civilization” or post-Neolithic societies. But because these immortality narratives are illusory, people are still left with their fear of death and non-existence. Existential angst, as Cave’s own (and unacknowledged) narrative goes, is supposedly universal.

The death stuff continued last night while reading Benedict Anderson’s Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (1983). Anderson locates the cultural roots of nationalism in a religious world-view, and explains why this view wins out over abstractions such as Marxism or Liberalism:

“The religions attempt to explain. The great weakness of all evolutionary and progressive styles of thought is that such questions are answered with impatient silence. At the same time, in different ways, religious thought also responds to obscure intimations of immortality, generally by transforming fatality into continuity. In this way, it concerns itself with the links between the dead and the yet unborn.”

The bogey-man here, the sensed but unseen ghoul, is death. To face down the ghoul, humans imagine themselves linked to a great chain of historical being: in the unborn past we are seed, in the living present we are flower, and in the dead future we are again seed. Continuity is thus maintained and immortality achieved.

If this death and immortality theme sounds familiar, it’s not surprising. Cave and Anderson are simply re-stating Ernest Becker’s Pulitzer Prize winning thesis in The Denial of Death (1973). Becker argues that civilization is an elaborate, symbolic defense mechanism that creates the illusion of immortality in the face of death.

Having had enough death stuff for a day, I finally turned to Stephen Greenblatt’s The Swerve: How the World Became Modern (2011). Much to my dismay, Greenblatt prefaces his paean to Lucretius with an extended mediation on his mother’s death obsessions:

“My mother was not afraid of the afterlife: like most Jews she had only a vague and hazy sense of what might lie beyond the grave, and she gave it very little thought. It was death itself — simply ceasing to be — that terrified her. For as far back as I can remember, she brooded obsessively on the imminence of her end, invoking it again and again, especially at moments of parting.”

Here was another omen, one which called to mind Nassim Taleb’s argument that modernity generates an information overload and the institutionalization of neurosis. This may or may not be true but I can’t help but think that death, or rather the fear of death, is the culprit.

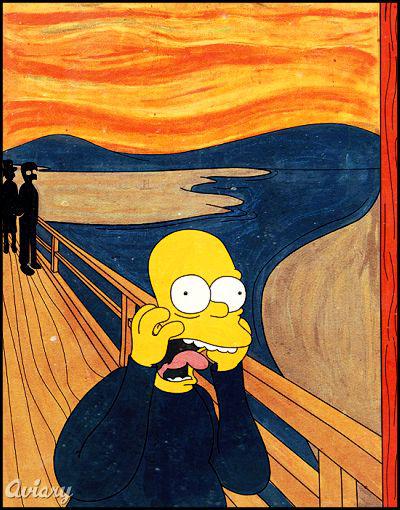

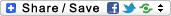

Edvard Munch's Immortality Project (just sold for $80 million)

Post-Neolithic societies have created and institutionalized a neurotic fear of death. As I explained here, this kind of existential angst is not a human universal. It has an origin, and can be situated in time and space. Death is a default condition of life. Fear of death is not. Just ask Bart.