Andrzej Zulawski's Possession does not begin as a horror film, but it certainly feels scary from the start. Mark (Sam Neill) returns after a long absence from some sort of top-secret work to find his wife, Anna (Isabelle Adjani), asking for a divorce. Mark is bewildered and, thanks to Zulawski's style and writing, so is the audience. Characters have cryptic conversations that leave tense space around the few, vague words. And these are the face-to-face chats; phone calls prove even more brief and confusing. For the remainder of the first hour, Possession unfolds less as a monster movie than a harrowing, exaggerated yet perversely insightful view of a marriage in total collapse. Zulawski wrote the film in the midst of his own messy divorce, and the swirling escalation of mutual loathing and violence serves as an exorcism of his pain.

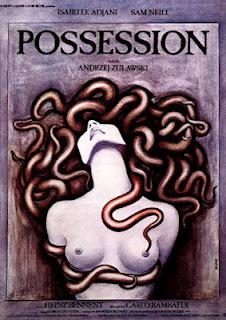

Andrzej Zulawski's Possession does not begin as a horror film, but it certainly feels scary from the start. Mark (Sam Neill) returns after a long absence from some sort of top-secret work to find his wife, Anna (Isabelle Adjani), asking for a divorce. Mark is bewildered and, thanks to Zulawski's style and writing, so is the audience. Characters have cryptic conversations that leave tense space around the few, vague words. And these are the face-to-face chats; phone calls prove even more brief and confusing. For the remainder of the first hour, Possession unfolds less as a monster movie than a harrowing, exaggerated yet perversely insightful view of a marriage in total collapse. Zulawski wrote the film in the midst of his own messy divorce, and the swirling escalation of mutual loathing and violence serves as an exorcism of his pain.Or, at least, that might have been the case had the film not gradually morphed into something even more terrifying and all-consuming, turning the film from a purge of self into a scorching of the Earth. What begins a repulsive display of two people locked in a private war ends up a unbearably nihilistic work worthy of H.P. Lovecraft. Like the great author's writing, Possession moves beyond human evil to touch upon a more unfathomable, vast energy that makes even the vicious fighting between the couple irrelevant. Yet Zulawski, whether out of the budgetary limitations that prevent a full-on dive into Lovecraft or merely his own writing skill, bridges the mortal with the cosmic. For the nightmarish horrors that eventually burst out of this demented film all stem from the various kinds of evil on display in the, for lack of a better term, "more realistic" scenes. Set in the shadow of the Berlin Wall and powered by sexual aggression and fear, Possession expands its contemporary and intimate anxieties ever outward until, at last, the universe goes nova.

I dare not say too much about what happens in the film, not because I'm concerned about spoilers (the film is 30 years old) but because to write down Possession's progression of mounting lunacy cannot capture the disjointed yet fluid manner in which Zulawski one-ups his horror. Suffice to say that amid the violent internal war and second half upheaval are vividly stylized emotional portraits of the effect of divorce on a couple, of the divorce on their child, of a miscarriage to an expectant mother, and of the sometimes perverse devotion of a mother's love. All of these themes exist together and blur with increasing frenzy as the film wears on, resulting in one of the most savage feminocentric horror films since Polanski's Repulsion. The only thing I'll say of Possession's many twists and turns is that it may be the first Western film to incorporate "tentacle porn." (I could provide a link to explain that term, but then I'd just urge you never to click it under any circumstances.)

Zulawski's camera never turns the early footage of a gruesomely straightforward marriage in crisis into documentary realism. Though he employs the occasional handheld shot for a rush forward into some terrifying action, the director chiefly relies on elegant, elliptical tracks that typically place characters in long shot, generating a disconnect that leaves gulfs of tense, charged space around the increasingly vicious squabbles and, later, the full descent into mania. A color scheme of pale blue casts the frame in a sterile, clinical tone, as if the whole world were a lab to monitor the (failed) experiment of mankind. Blocking alone subverts expectations, such as a scene where Anna and Mark meet in a restaurant but sit in adjacent booths, forcing each to face away from the other and proclaim their grievances aloud.

Arrhythmic editing also throws off expectations and complicates the feeling of something being...off about everything. Harsh cuts tend to leap locations and time without warning, a fight suddenly running into a shot of Mark picking up his son Bob from school. Zulawski has clearly removed several steps in travel and mood change, but the mere act of joining such disparate elements blends the two tones so that the banal minutiae of the latter flecks the visceral charge of the former, and the former's horror slithers under the latter's otherwise unaffecting filler scene. Even basic shot-to-shot cuts within the same scene lack continuity: after Mark hauls off and gets particu larly violent with Anna, she stomps out into the street as he chases her. Suddenly, a left-to-right lateral track of the couple sharply cuts 90 degrees into a sort-of POV shot of Anna having already wheeled around to confront Mark and rushing toward him. One second, maybe two, of action has been lost between the two shots, but the effect is so disorienting as to make an already disturbing scene almost profoundly off-kilter.

My favorite bit of camera trickery, though, involves the Zulawski and his cinematographer Bruno Nuytten use focal lengths the way Gaspar Noé utilized low-frequency sound in Irréversible, to subtly magnify a sense of unease and discomfort until the agitation of the film's extreme content becomes inseparable from the kind inflicted upon the audience near-subliminally. A wide-angle lens further exaggerates Mark's dramatic rocking toward and away from the camera in one shot, the focus constantly shifting between Mark in the foreground and Anna behind him as he moves in and out of frame. Elsewhere, Zulawski uses lenses to warp perspective in the background, stretching the depth of the frame until every character who walks into the distance appears to be pulled by some force as if approaching an event horizon for some unseen void. This gives each shot its own tension, as one cannot know whether the character will be able to escape at the end or be sucked into oblivion.

Zulawski's formal daring is matched only by his leads' willingness to go as far as the story needs them. Sam Neill yet again proves that he is apparently a prerequisite for a good Lovecraftian movie (see also: In the Mouth of Madness, Event Horizon). He explodes routinely throughout the film but is never scarier than when he manages to keep his screams lodged in his throat, the building pressure of this suppression contorting his face into a grim mask of bulging eyes and bared razors for teeth. Adjani is even better, her unhinged insanity combining relationship, pregnancy and miscarriage fears into shrieking madness punctuated by her own moments of calm super sanity that serve to marshal her own fears and agonies onto the world at large. Both actors end up playing their own doppelgängers, making already dizzying performances incomprehensible. The side players generally emphasize the mood of impending doom, so grotesque yet static that they appear as manifestations of the stark but corrupted Berlin. That is, until the moment they see the face of what's coming, at which point their atmospheric remove turns into overwhelming terror. Possession ends with the apocalypse, with the sound of bombers and their exploding payload almost a welcome relief from the force that controls them. As with the editing of the rest of the film, the movie ends suddenly, a sudden brake that sends the audience lurching forward into an uncertain world, still carrying the momentum of its nightmarish implications. Compared to that, getting hit with a firebomb is almost the easy the way out.