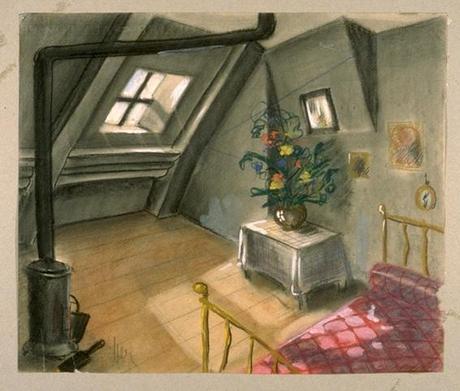

(Photograph: Sous les toits de Paris, by Lazare Meerson)

I. The Cissé connection

❧

T he first curve in the car race at Pau, the first ever to be called Grand Prix, is the station hairpin. After that, the road climbs on the Avenue Léon Say and then merges into a narrow tunnel. If we believe the Alfa Romeo mechanics, Tazio Nuvolari dominated the race back in 1935 with a single swoosh; if we believe those who attend every year along the stone viaduct, the track, which is 2,769 meters long, has remained beautiful and unchanged since then. We can imagine the Pau society getting excited about Nuvolari and his sleek Italian car under the immense straw hat of Parc Beaumont or the Casino garden: with women celebrating upwardly mobility through their muslin dresses and fancy muzzles of pet dogs. This is where the Mercedes-Benz models forever cauterized the heart of the local aristocracy, and this is also where the unmistakable connection between three distinct Cissé sportsmen begins—not exactly a symbol or a metaphor, but what Wittgenstein would call a family resemblance. Gradually, in the threefold Cissé footballing history, the early, inchoate stirrings of dissatisfaction in each player’s career, the time of boredom and discontent (but not yet of apparent deterioration), start coming all together. The movement from fantasies to reality is not unlike that of Emma Bovary, in Flaubert’s celebrated novel, whose downward shift is through financial dissipation as much as sexual corruption.

The Islamist victory wasn’t engineered, but it. During the voyage that takes Emma from Tostes to Yonville, she and Monsieur Lheureux, an art dealer and part-time usurer, spend much time searching for a missing greyhound and exchanging soothing stories about lost dogs who returned to their masters. Like for the Cissé journeyman, a type still largely unexplored in modern soccer, the false comfort of these consoling tales would pursue Emma for the rest of her life. What happens to either dog or footballer, however, and the desire of those who wander off, is not recorded.

II. The Cissé compendium

❧

N ot sufficient study, to my mind, has been made of the discreet distance that three separate Cissé, all born or trained in the South of France, kept with each other. They flickered into brief existence, sometimes in England, sometimes not; we rarely know why and how they were signed, or even why and how an allure of secrecy was thought to be necessary around their contracts. (Typically, these consisted of a loan-deal whose fulfillment first appeared suffused with high confidence and then ended up cramped, whether for rambling lunacy or romantic disaffection.)

They moved from the bare wooden perch of childhood into world-class football. They embraced their respective jerseys with such abandon as to betray a certain fragility—the philosophical élanof somebody throwing his arms around a friendly Newfoundland, without properly considering matters of size and weight. On the pitch, however, they were often found lost, helpless, tortured, fallen. Forgettable and unforgettable moments about the three players drop into the fog of history, like a crooked tie straightened at the mirror-bulbs or a soft dune flattened in the desert. Let us assemble the known facts:

(Illustration by Akitaka Ito)

❧

a) In 1981 Mangué Cissé, a former footballer who captained the team of Ivory Coast before his move to the Provençal city of Arles, has the seventh and last child of his family, Djibril, who is later noted for his weak shin bones.

a) The bull-fights produced throughout the 1990s in the Roman arena of Arles are marvelous, if occasionally bloody; their broad and powerful sonority, almost unbelievable. While animal violence hurts and troubles his artistic soul, the uproar and tremor of the crowd leave a lasting impression in Djibril’s acoustical system, like the two f-shaped openings in a Stradivari violin.

b) In 2002 the coach of West Ham is fascinated by midfielder Édouard Cissé, nonchalantly crossing his long legs, during trial, like a King Charles spaniel under a small table holding a collection of Sèvres porcelain. He snaps him up from Paris to play (one season on loan) for the Hammers.

c) Sometimes in 2004 the young Malian Kalifa, also a Cissé and a trainee at Toulouse, captures the attention of a Portuguese scout who brings him over to GD Estoril.

c) In 2005 Kalifa, shuttling with some zest in and out defensive midfield duties, signs for Boavista.

a) In 2006, during a warm-up match against China, Djibril’s leg twists once more under him; the fractured tibia requires immediate surgery, and fellow striker Thierry Henry—himself moving off balance, in fierce, vulture-like strides—is moved to wander about another generation of French footballers wretched by chance.

b) In 2007 Édouard, who was born twenty-nine years earlier in the small city of Pau, on the northern edge of the Pyrenees, decides to end a tortuous decade of service for Paris Saint-Germain and signs with the sulphuric club of Beşiktaş. (During Édouard’s quite successful time in Turkey, his birthplace is used many times by the Tour de France: notably, as a departure town on the way to the impervious and fearful Col du Tourmalet.)

c) In 2009 Kalifa—uprooted and at times so tired that he feels he’s liquefying like an old Camembert—unexpectedly finds himself a fan favorite, scoring a crucial goal against Wolves and giving his best for manager Steve Coppell, first at Reading and now at Bristol City.

b) In 2009 Édouard returns to France and plays two seasons for Marseille, soon to realize that streets and alleys of the places where he played recently all look the same—a crooked and damp version of Rue Tran in his native Pau; a return match against Saint-Germain enables him to bask in the Parisian sun again, like a stuffed crocodile brought back from the East.

a) Early in 2011, after a famous hat-trick scored for Marseille and a brief English stint with Sunderland, Djibril’s impressive career appears to have reached, in Athens, an apex of physical exertion and sport records. His enthusiasm is matched by the legendary extravagance of his clothes—making of Djibril a thespian of the small box. This wild period includes: protracted racial abuse, kicks and punches by invading Olympiakos fans after a 2-1 victory in the city derby by Djibril’s Panathinaikos, enormous platters of moussaka and roasted peppers stuffed with rice, and the extraordinary number of 23 goals in 28 appearances. Note: If we are to complete the list of Djibril’s footballing accomplishments and dealings, we must record that a delegation from Lazio (the team where he currently plays) approaches him with details about a contract. Determined to secure the player’s emotional commitment after the infernal hubbub in Athens, the Roman managers decide to speak in French. Djibril is stunned. Ah, quelle surprise! Vous parlez français?

❧

Of the Cissé players listed above, the only one about whom we have proper information is Djibril. The other two grew, recovered, and staggered on through the years. Both of them kept exceptionally cold in the whirl of events that brought their football, respectively, to Auxerre and to the English Premier League. Their career has been streetwise, brief, tactful—nibbling on the edges of world-football for half a paragraph or so. Swift and self-satisfied, the lesser-known of the three Cissé played the part of the experienced part-timer in the fold of a coach. Édouard and Kalifa ran in neat circles, like a greyhound yapping after butterflies or chasing poppies in a cornfield. Their calm and somewhat melancholy beauty would make other footballers jealous, when they repeat to themselves, Oh God, why did I come here?As armies and seasons pass, as policemen fire their pistols in the air at the olympic track, the more ordinary means by which athletes like the Cissé progress from shelter to shelter are either lost or blurred. What happens when they saddle up to inhospitable terrains is not recorded.

(Illustration: Barkely L. Hendricks, Bahsir, 1975)

III. The Cissé romantic

❧

A m I to be a king or a pig? Gustave Flaubert writes in his Intimate Notebook. For a footballer, it never looks as simple as this. There is life, and then there is the non-life; the life of ambitions fulfilled, and the life-time of injuries. Others try and tell you about your future, but you never really believe them. You’ll learn how to dance again, you’ll be back stronger than before. (When you’ll see it, you’ll believe it.) On 30 October 2004 Blackburn’s Jay McEveley and Djibril Cissé, at the time in which his career seemed to be morganatically united with Liverpool, challenged for the ball. In a handful of mundane, horrific seconds Djibril’s eyes began to look into a post-apocalyptic wasteland, with semi-abandoned hamlets and toxic gases oozing from the grass; in his mind, the boot caught in the turf, the pins inserted in the leg, the fear to loose everything below the knee shrank and distorted the reality like a brass plaque under the rain or some optician’s chart. The memory of this dramatic incident, and its presence too, pursued Djibril for the rest of his life. A Byronesque soldier of fortune born outside of the British aristocracy (we’re at liberty to laugh about heraldic matters, but the man from Arles, besides his pompous marriage in a tuxedo in the red of Liverpool, gained the title of Lord of the Manor of Frodsham and refused the permission to hunt in the Cheshire Forest), Cissé came close to deteriorate morally while in Greece, but he also retained that magnificent look of a dragoman reading his Plutarch on the battlefield.

At Lazio, he became the final companion of Miroslav Klose. An unlikely couple: the stout, German juggernaut and the sleek, dandified Frenchman. The old-fashioned goal-poacher, and the wandering adjunct-striker, first employed on the wing by Rafael Benitez. Klose’s attacks are always a storming of the citadel (whose walls exist only in his brain); his goals originate from the hypodraulic mechanism of the body, messages conveyed by pistons, plugs and wires (within that 4—2—3—1 system he knows so well). Cissé’s attacks are introduced by a much more volatile fluid that ignites with electricity, operating asymmetrically and only after a great deal of frivolous scribbling and pickpocketing; his goals (rather spare, as of late) are made of flexible, caressing tones—a learned, bespectacled insect stabbing at the end of a parasol.

Both Klose and Cissé are fundamentally out of place in Rome. But the proud German is comfortable with the Furtwängler attitude of adapting acoustically everywhere, even to an environment which was not made for the muscular harmony of timpani and trumpets; the dizzy Frenchman, instead, is a diva waking up after a transatlantic journey, like Sarah Bernhardt in tour to Rio de Janeiro.

To paraphrase the combinatory terms of Stanisław Lem, Klose is a word sequence in K, Cissé in C. One’s work is at times knotty, kaleidoscopic, and knowingly kinetic. The other’s is both cheap and caustic, callous perhaps, the creature of a cosmopolitan charmer. Food from the lunch tray is delivered and dealt by Klose in fast and agile motion, for every part of the day is an Italian miniature of the cities of Germany, Poland, and Switzerland; the meals of Cissé—the white beard tickling his mulatto skin, as a sign of interior anarchy—exude that sensation of longing, at once sweet and painful, that the Brazilians call saudades.

If Klose and Cissé ever befriended each other, as it seems almost certain, they must have done so in the manner of fellow-lodgers at a bohemian pension in Paris during the 1890s: the sort of place where washing is done in enamel basins, the adult sleeping arrangements are negotiated with cats plus a stack of bedtime reading, and one wakes up with the remains of cognac or coitus. This is what actually happened to Jean-Jules Verdenal, a round-faced, inoffensive, mustachioed medical student who was born at Pau in the French Pyrenees (like Édouard Cissé), and the stiff, punctilious American poet T.S. Eliot. Precisely what came out of discussions during breakfast at Mme Casaubon’s table, when the two men stared the sad household wallpapers and tucked in napkins to think about a generation that was soft and ripe for sacrifice, is not recorded, even though we know that Verdenal is looming over T.S. Eliot’s great poem The Wasteland. What happens when Klose and Cissé meet up, one collarless and in sneakers, the other in leather jacket and vintage apparel (much more his kind of thing) is also not recorded. ♦