Book Review by Chris Hopkins.

Frances Brett Young in his ‘Author’s Note’ starts by referring to a novel he published three years earlier:

Some years ago, when I published a book called This Little World, I was assured, by a multitude of correspondents, that they knew not only the village of which I had written but the people whose portraits I had essayed. Needless to say when I wrote it, I had no actual village in mind; and never in my life have I been so foolish as to write of living people. It is the same with Monk’s Norton. I take this opportunity of declaring that no village like it has ever existed outside my imagination; that the people whom I have devised for its habitation are, equally, wholly imaginary.

This is of course a conventional disclaimer of factual reference and indeed I have every faith in the novel’s fictionality. However, one of the text’s most striking features is actually its strongly objective approach to its task: it seeks to describe in an exact topographical/hierarchical order the village and its inhabitants at the exact present but in such a way that the relatively long past of the place is also recorded. The book’s approach to Monk’s Norton begins with the perspective of a cuckoo and in many ways retains that aerial view-point throughout, though fairly soon transferred to an evidently omniscient and human narrator.

The opening of the novel, ‘Prelude’, is striking in its non-human perspective in describing the transformation of hairy caterpillars in the African veld into chrysalises, depriving the cuckoos of their main food:

After a while, the cuckoos, which (save in the shelving of domestic duties) are silly birds, discovered that what they had regarded as a temporary hitch in the caterpillar-supply was a permanent breakdown. By this time they had become too hungry for anger (p.4)

Soon the cuckoos make their extraordinary migration to Britain, and three to Monk’s Norton:

One dropped to the field called Long Dragon Piece, hard by Good rest Farm. The Second flew straight to the belt of elms which embraces ‘The Cubbs’ at the back of the Sheldon Arms. The third slid swiftly towards a tall lime tree whose shadow fell on the eastern wall of The Grange. This last, less tired than his fellows, broke silence as he flew. Cuckoo, he shouted, cuckoo, cuckoo, cuckoo! And the others lazily answered him (pp. 7-8).

This non-human perspective introduces from an odd angle the systematic human overview that forms the structure and in most respects the plot of the novel which in turn visits two essential and ancient edifices and then the spatial divisions representing and containing the different (and indeed separated) social levels of the village:

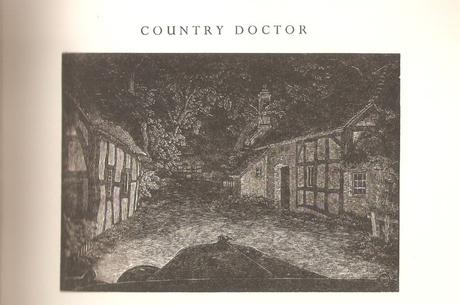

Only one chapter heading focuses on an individual, or anyway an occupation, rather than a location or social group: ‘Country Doctor’. And indeed the village doctor turns out to be a quietly heroic figure: ‘If he is not particularly gifted or skillful – and he doesn’t pretend to be either – he is kind and honest and wise and courageous and merciful … it would be difficult in Monk’s Norton to find a more happy man’ (p.83). Brett Young had himself been a doctor, of course, from 1906 to 1918.

The ‘Portrait’ is very aware of history and tradition, but also sensitive to both the change which is affecting Monk’s Norton, and that which has passed it by. On the whole, the village is isolated:

It has always, in fact been rather ‘out of the world’, and seems likely to remain so. Though main railway lines run North and South n either side of it … the nearest station is five miles away, and few trains stop at it. No high-road of greater importance than one of the ancient salt-ways, which lost its identity before the last pack-horses vanished, has ever run through it (p.12)

Nevertheless, things are changing. There is the case of Mr Webber the saddler:

Mr Webber’s father kept the shop before him and did steady trade, no doubt, in traces and horse-collars and shining brass hames and saddles; but the petrol age, which has carried George Mason triumphantly up in the world from the state of a mere dabbler in the elementary mechanics of bicycles to that of a garage proprietor, a ‘stockist’ of tyres and spare-parts, and the owner of the brown bus, has reduced poor Mr Webber, a craftsman without a job, to the condition of a retailer of dog-leads and muzzles and purses and such leathery trifles, while the remains of the stock in whose making he took so much pride accumulate dust … no man who is looking to buy a Fordson [tractor] will throw away money on new harness (p.24).

Monk’s Norton has pastoral aspects, but it is not Eden. There are some thriving farmers, including Mr Collins and son who have adopted the most modern farm machinery, but also a farmer like Mr Hallow who is constantly on the verge of failure, and for whom ruin will come soon: there will be ‘no reprieve for him’. (p.130). Some recent ‘incomers’ (what the thatcher, Shelton, calls ‘antelopers’, p.96) have moved to Monk’s Norton exactly on the basis that it will be rural perfection – but the narrator quietly uncovers for us their self-deception. There is Mr Rudge who inherits some land in the village and moves there aged forty after working ‘in business’ (probably as a book-keeper – he is convinced that correct figures and calculation can solve everything). Sadly, his calculations do not seem to anticipate the real challenges of agricultural life, and he does not seem to acquire any further expertise as he goes on. Mixed farming fails to yield returns, and then so do apples, and bees, and jam-making, and rhubarb-forcing, and mushroom-growing. He finally settles for plums which just about keep him alive. Still, he will always tell you that ‘no life can compare with that of a small-holder’ (p.106). The Portrait ends with the cuckoos, who having foisted their eggs on other parents, eat all the available caterpillars in Monk’s Norton, and then head back to Africa.

I very much enjoyed this novel (though in many ways it did not seem like a novel) and would recommend it. It is earlier, but reminded me of another rural work which I admire, Flora Thompson’s Lark Rise to Candleford (1945 – published first in three separate volumes in 1939, 1941 and 1943). Both narratives are certainly in the pastoral tradition, and, like all true pastoral, balance the comforting and the harsh, evoking the (imagined?) values, customs, and past of the countryside, while also showing that change and decay are always already there: ‘et in Arcadia Ego’. I know that a few of my reading group colleagues found what sounded like some rather careless writing in other novels by Brett Young, but Portrait of a Village is carefully written (though completed in only five weeks in 1936), and perhaps the care is partly inspired by both the rural project and by the admirable woodcuts by the distinguished wood-engraver Joan Hassall, which add a great deal of atmosphere both peaceful and melancholic to the pastoral scene. Here is her image accompanying the account of the country doctor going to deliver a woman’s first child in the middle of the night (p.81). The rendering in wood-engraving of the view through the car windscreen, and the lighting by the headlights of a little space of the road immediately ahead and then more dimly the ancient cottages beyond is superbly done, and surely portrays a welcome aspect of modernity in Monk’s Norton.

See her Wikipedia entry for an introduction to her career: Joan Hassall – Wikipedia.

I rather think I should read Ronald Blythe’s Akenfield: Portrait of an English Village (1969) next, which I suspect will have some kinship with Brett Young’s novel.