In the two items I've posted this morning, I've alluded to comments that Pope Francis made this past Sunday in his Angelus reflections in Rome. In these comments, Francis emphasizes a core teaching of the Catholic tradition: this is the sacred obligation of all Christians to follow their informed consciences.

Francis notes that Jesus himself provides a model for us as we struggle to listen to God's voice in the depths of our souls, and to respond to that voice. Jesus was not a "remote-controlled" automaton who automatically knew what was right or wrong to do, Francis insists. Like the rest of us humans, he prayed, sought to discern God's will, and struggled to be faithful to God's will.

Francis tells his listeners:

So we also must learn to listen more to our conscience. Be careful, however: this does not mean we ought to follow our ego, do whatever interests us, whatever suits us, whatever pleases us. That is not conscience. Conscience is the interior space in which we can listen to and hear the truth, the good, the voice of God. It is the inner place of our relationship with Him, who speaks to our heart and helps us to discern, to understand the path we ought to take, and once the decision is made, to move forward, to remain faithful.

What strikes me as I read Francis's remarks and discussion of them (e.g., by Robert Imbelli and Commonweal readers, and by Carol Glatz and National Catholic Reporter readers) is how both surprising and unsurprising it is to hear this venerable, traditional Catholic articulation of the role of conscience in the Christian life from the lips of the new pope. We Catholics have, after all, lived through a period of Catholic history in which two previous popes have made it appear to us that we layfolks are, in fact, very much remote-controlled automatons who are commanded to obey each and every utterance of the papal mouth.

Without question. Without thought. Without prayer or struggles of conscience.

Because the Holy Father says so.

And so it sounds astonishing to us now to hear a pope saying something about the primacy of conscience in the Christian life that sounds as if Thomas Aquinas or John Henry Newman (or Vatican II, following both of those classic theologians) might have said it. What a strange place we've come to in our journey as a Catholic community, when the classic theological notions of conscience defended by the last ecumenical council of the church now sound so novel, so refreshing, so bold and courageous!

Those of us who were theologians and who wrote about the moral life under the past two popes were often severely punished, even removed from our jobs, for saying what Aquinas, Newman, and Vatican II said about conscience. We were told that we did not give enough room to the binding force of papal utterances in our work, if we implied that Catholic consciences could and should struggle with church teaching as conscience forms itself.

We were told that there is no room for disagreement with church teaching--that a properly formed conscience never questions or disagrees with anything a pope says.

I myself was forced by Loyola's (New Orleans) Institute for Ministry to revise a textbook in fundamental ethics I had written for that program in the late 1980s, which received high praise from my peers around the country who reviewed the textbook, but which became problematic after John Paul II and Cardinal Ratzinger began their crackdown on Catholic theology programs in the early 1990s. I was told that, within a space of a few years, the textbook had become problematic because it implied that an authentic, formed Catholic conscience might struggle with magisterial teaching.

I was instructed to revise the textbook to make this point more clear--especially in the area of sexual ethics. A Jesuit was placed over me as censor as I rewrote the textbook. Insofar as I know, the textbook I then produced was discarded and not used, because it did not do enough to bind the consciences of Catholics with papal utterances, especially in the area of sexual morality.

To repeat: when I first wrote this textbook in the latter half of the 1980s, theologians and church officials around the country who read it praised it as a faithful articulation of classic Catholic teaching about moral issues. It became problematic solely because of John Paul II's and Ratzinger's attack on theologians in the next decade.

And so we're now at a point at which the witness of one theologian after another, who was, after all, only citing the most traditional church teaching on these points, has been suppressed, obliterated, treated as an unfaithful articulation of Catholic teaching. We're at a point at which the struggles of lay Catholics for many years now to deal with papal teaching about artificial contraception that a majority of Catholics in the developed nations reject on grounds of conscience count for nothing--and have nothing at all to teach the church and its leaders.

We're at a point at which the lifelong, difficult struggle of LGBT Catholics to obey our consciences and listen for God's voice in the depths of our humanity counts for nothing in the public discourse of the Catholic church about conscience or about homosexuality--because such Catholics are treated as the other insofar as we claim their gay humanity, and our very nature as gay human beings is treated as the antithesis of what it means to be Catholic, so that our faithful witness is obliterated within the official discourse of contemporary Catholicism.

No room is made for this witness in the public square as part of the voice of the Catholic church today--no room at all is made by church officials for this witness in the public square, as they claim that their voice and their voice alone counts as the Catholic voice in the public square.

And the result of all of this--the suppression of the faithful witness of theologians called to serve the church by listening to the Spirit as theologians, of lay Catholics living their sexual lives as responsible stewards who dissent from official teaching about contraception and homosexuality on grounds of conscience--is a deep, tragic impoverishment of Catholic discourse in the public square. When these voices count for nothing but the tarnished voices of bishops like Cardinal Dolan count for everything, then it is now wonder that the influence of Catholicism in the American public square has waned almost to the point of insignificance at this point in the history of the nation.

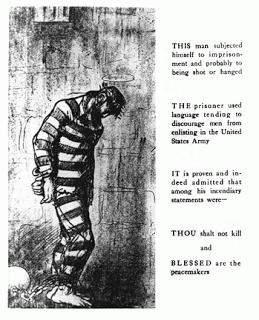

The graphic: George Bellows's depiction of Jesus as a conscientious objector, published in 1917 in The Masses, from Wikimedia Commons.