Reposted from a year and a half ago. Miyazaki is always worth thinking about.We know, of course, that cartoons aren’t just for kids, right? Many exist in what I’ve come to call “universal kid space”; they’re fully accessible to children, yet are compelling to adults on their own terms, and not just vicariously through children. In thinking about Hayao Miyazaki’s Ponyo I’ve been thinking about the adult aspect of the film. What’s here for adults?

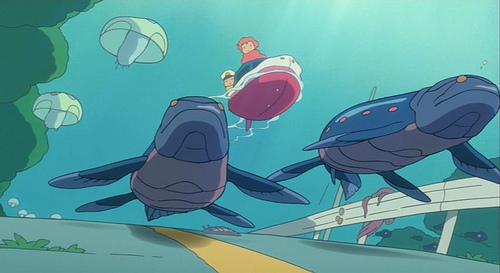

There is, of course, the visual beauty. The film is a joy to behold and the animation is often astounding, such as the sequence where the sea comes alive as Ponyo runs atop the waves to meet Sosuke:

But what about the story? It’s simple enough that a young child could follow it; Miyazaki has said he made it for five year olds (in an interview included as extra on the Disney DVD). There are two things I find puzzling at the heart of the story. One, that Ponyo should so badly want to be human. Why? It doesn’t seem to follow from any particularly compelling psychology. She just wants to be human and that’s that. Two, given that she wants to be human, why should that desire throw the whole world into turmoil? Why couldn’t the effects of that desire be more local?

I think we have to take the psychology as given. That’s just the way things are. As for the cataclysmic effects of Ponyo’s desire, that’s what Miyazaki was reaching for. On the emotional side, let me quote from Mark Mayerson:

Miyazaki's subject here is love, though not romantic love and certainly not sexual love. What the characters in this film are missing is devotional love. Just about every character in this film has been abandoned in one way or another.That is, the film starts with a world of lonely, isolated people. It ends quite differently. As Mayerson says:

The nursing home that Sosuke's mother Lisa works at is next door to a school (or is it a pre-school?). In each case, the old and the young have been isolated from the world of adults. The old women in the home are, I presume, widows, and their children are not taking care of them. The children in school are not being looked after by their parents....

Both Sosuke and Ponyo have two parents, but those parents are not together. Sosuke's father is captain of a ship and over the course of the entire film, he never gets off it. . . . Ponyo's mother is a goddess who is not present in Ponyo's home and who only interacts with Ponyo once during the entire film.

It is Ponyo's actions that release the magic that results in the flood. This flood is the catalyst for everything that follows and the reintegration of what has been separated. Extinct fish once again swim in the ocean, uniting past and present. The old women are able to walk again and rejoin the adult world. The goddess and Fujimoto are brought together. Sosuke's father is able to bring his boat back home.The film is thus not simply about Ponyo and Sosuke, but it is about the renewal of the world, a profoundly metaphysical, not to say religious, theme. But how do you present such an idea to a world of cynical adults? Simple, you package it as a fantasy for young children.

In that same interview where he explained that made this film for five year olds Miyazaki also said:

I often think about the relationship between nature and me, a human. I exist within nature, but also there’s nature in me…that is somehow connected with Mother Nature. We neglect the fact that we are products of nature. We suppress that by following society’s rules. We possess primal powers and desires…and that is nature. So I wanted to release them.And so he created this film in which the sea itself in an animate being, with eyes; in which the moon comes so close to the earth that it disturbs the oceans; and in which creatures long extinct live once again. A five year-old with a fluid sense of the world can accept such things at face value. For a adult to accept such things, that adult must, in effect, suppress “society’s rules” and think the world anew.

And it’s the crossing of the line between animal and human that sets things off, and provides the emotional nexus of this transformation. That line is very important in human culture and it is at the heart of Miyazaki’s story craft, as we’ve seen in Porco Rosso, Spirited Away, and My Neighbor Totoro.