Air pollution particles from coal-fired power stations are more harmful to human health than many experts realized, and are more than twice as likely to contribute to premature deaths as air pollution particles from other sources, new research shows.

In the study, published in the journal Science, colleagues and I mapped how emissions from U.S. coal-fired power plants traveled through the atmosphere, then linked the emissions from each power plant to the death data of Americans over 65 on Medicare.

Our results suggest that air pollutants released from coal-fired power plants were linked to nearly half a million premature deaths among older Americans between 1999 and 2020.

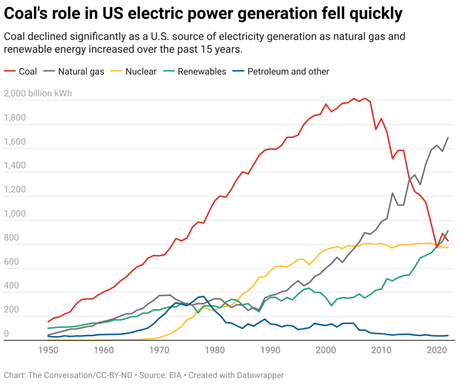

It’s a staggering number, but the study also has some good news: The annual number of deaths from U.S. coal-fired power plants has fallen sharply since the mid-2000s, as federal regulations forced operators to install emissions scrubbers and many utilities shut down coal-fired power plants entirely .

According to our findings, in 1999, 55,000 deaths in the US were due to air pollution from coal. By 2020, that number had dropped to 1,600.

How PM2.5 levels from coal-fired power stations have declined since 1999. Lucas Henneman.

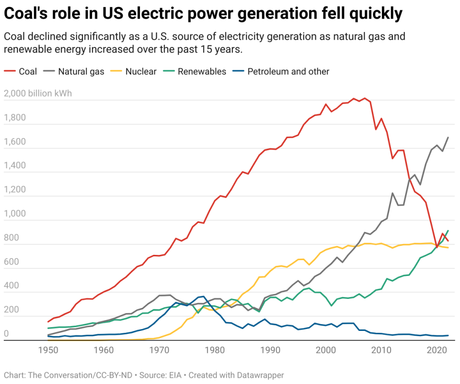

In the US, coal is being replaced by natural gas and renewable energy to generate electricity. However, globally, coal consumption is expected to increase in the coming years. That makes our results all the more urgent to understand for global decision makers when developing future policies.

Air pollution from coal: what makes it so bad?

A landmark study from the 1990s known as the Harvard Six Cities Study linked small particles in the air called PM2.5 to an increased risk of premature death. Other studies have since linked PM2.5 to lung and heart disease, cancer, dementia and other diseases.

Following that study, the Environmental Protection Agency began regulating PM2.5 concentrations in 1997 and has lowered the acceptable limit over time.

PM2.5 – particles small enough to be inhaled deeply into our lungs – come from a variety of sources, including the combustion of gasoline in vehicles and smoke from wood fires and power plants. It consists of many different chemicals.

Coal is also a mixture of many chemicals: carbon, hydrogen, sulfur and even metals. When coal is burned, all these chemicals are released into the atmosphere as gases or particles. Once there, they are transported by the wind and interact with other chemicals already in the atmosphere.

As a result, anyone downwind of a coal-fired power plant can inhale a complex cocktail of chemicals, each with its own potential effects on human health.

Two months of emissions from Plant Bowen, a coal-fired power plant near Atlanta, show how wind affects the spread of air pollution. Lucas Henneman.

Coal PM2.5 tracking

To understand the risks that coal emissions pose to human health, we tracked how sulfur dioxide emissions from each of the 480 largest U.S. coal-fired power plants ever in operation since 1999 traveled with the wind and into small particles changed: coal PM2.5. We used sulfur dioxide because of its known health effects and dramatic reduction in emissions over the study period.

We then used a statistical model to link coal PM2.5 exposure to Medicare data on nearly 70 million people between 1999 and 2020. This model allowed us to calculate the number of deaths associated with coal PM2.5.

In our statistical model we took into account other sources of pollution and took into account many other known risk factors, such as smoking status, local meteorology and income level. We tested multiple statistical approaches, all of which produced consistent results. We compared the results of our statistical model with previous results testing the health effects of PM2.5 from other sources and found that PM2.5 from coal is twice as harmful as PM2.5 from all other sources.

The number of deaths linked to individual power plants depended on several factors: how much the plant emits, how the wind blows and how many people inhale the pollution. Unfortunately, U.S. utilities have located many of their factories upwind of major population centers on the East Coast. This location enhanced the impact of these plants.

In an interactive online tool, users can look up our estimates of annual deaths associated with each U.S. power plant and also see how these numbers have fallen over time at most U.S. coal-fired power plants.

An American success story and the global future of coal

Engineers have been designing effective scrubbers and other pollution control devices that can reduce pollution from coal-fired power plants for several years. And the EPA has rules specifically designed to encourage utilities that used coal to install them, and most facilities that didn’t install scrubbers have closed.

The results were dramatic: sulfur dioxide emissions dropped by about 90% in facilities that reported having scrubbers installed. Nationally, sulfur dioxide emissions have fallen by 95% since 1999. By our count, every factory that installed or closed a scrubber has dramatically reduced the number of deaths.

As advances in fracking techniques lowered the cost of natural gas and regulations made running coal plants more expensive, utilities began replacing coal with natural gas plants and renewable energy. The shift to natural gas – a cleaner fossil fuel than coal, but still a greenhouse gas that contributes to climate change – led to even further reductions in air pollution.

Today, coal supplies about 27% of electricity in the US, up from 56% in 1999.

Globally, however, the outlook for coal is mixed. As the US and other countries move toward a future with substantially less coal, the International Energy Agency expects global coal use to increase at least through 2025.

Our research and others like it make clear that increased coal use will harm human health and the climate. Making full use of emissions controls and a shift to renewable energy sources are surefire ways to reduce the negative impacts of coal.

This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent nonprofit organization providing facts and trusted analysis to help you understand our complex world. The Conversation is reliable news from experts. Try our free newsletters.

It was written by: Lucas Henneman, George Mason University.

Read more:

Lucas Henneman receives funding from the Health Effects Institute, the National Institute of Health, and the Environmental Protection Agency.