In our post Creative Policy Analysis we argued that Classical Rational Policy Analysis and interactive policymaking are basically reacting to existing problems that, for some reasons, get “high on the societal agenda”. Notwithstanding that, we discussed some possibilities to make policy analysis more creative.

However, a real innovative policy can only come about if policymakers redefine themselves as designers instead of reactive problem solvers. In this post we will show you this approach.

Designing something new

Designing is devising and sketching. The process of designing usually involves trying something on paper, visualizing, speculating, making creative use of mistakes. Designing is also planning or drafting. The design process is stubbornly focused on making something possible. The reason for this may be a new technological possibility, a wish, an interesting possibility or a completely new concept. Or an annoyance that everyone has become used to.

Designers are not problem solvers or societal plubers but engineers, composers, architects, visual artists and comedians. They want to achieve something new and give it a form. Policymakers could be too. Government buildings then become constructive policy ateliers.

Social designs

Social designs have a long history. Interesting are the grand design of democracy in Athens, the idea of laws in Rome and the concept of mercy from Jerusalem. Other major social designs are the separation of church and state, and of the separation of the legislative, the government and the judiciary.

Other, less “grand” social designs as a public reading library, a soup kitchen are from more recent date. For some more practical examples of rather new social concepts, read our post Innovation of Social Concepts..

The design process

You often see a designer first reducing situations to their bare essence, ignoring all kinds of complicating details. They often drop one or more aspects, and pretend that there is already a practical solution for that, or that it will arise. They actually think backwards. There is a vague contour of something that could be, and then they work back to make that, or parts of it, possible.

Design from values

One approach you can take in designing a innovative policy is to start from a worthwhile value and forward thinking how to implement the value in the design.

An important value in designing a government building could be that department employees are automatically invited to collaborate more with neighboring departments. Making coordination from hierarchy less necessary.

The design could be a layout of the building where the rooms belong to a different department are alternately located along a corridor. Another design could be that the rooms of one department are on one side of a corridor, and those of the other department on the other side.

The value of both designs lies in the fact that the employees are still close to each other, but also to those of the other department. The possibility of accidental interactions that can lead to effective collaboration has been increased.

More about Designing by Using Value in this post.

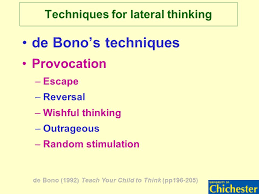

Design by escaping from taken for granted

Design something new by escaping from what is normal, unquestioned or too obvious.

A generally accepted feature of a refrigerator is that the thing can’t stand near a stove. Could you design an integrated refrigerator / stove, in which the heat produced by both devices is used for each other?

The opening sentence of a story could be this: Every day Sylvester went to school. Provocation of the ordinary by turning around (the school went to Sylvester) and by exaggeration (once a year) could lead to a unlikely, but therefore exciting opening sentence of the story: “Once a year Sylvester wakes up in the same bed as he had gone to sleep the night before. But now that bed was in the school ”.

Complete the story by using as many provocation techniques as possible.

Design by setting up Provocative Operations

Provocations can be set up by the use of any of the provocation techniques—wishful thinking, exaggeration, reversal, distortion, or random stimulation. The policy designer creates a list of provocations and then uses the most outlandish ones to move their thinking forward to new ideas.

A dishwasher that you would not have to clear out would be ideal.

Why should dishwashers be cleared? Because the clean dishes must make way for the dirty dishes. Why actually? Because there is only one dishwasher. Why haven’t we two dishwasher to use alternately? Because it costs too much!

This Provocative Operation could lead to dishwashers being supplied with two racks, one for in the machine with dirty dishes to be washed and one for the counter with the clean dishes, ready to be used.

In a court case, the parties try to convince a judge that they are right. The judge weighs the arguments and interests, and then comes to a decision that is “the most reasonable”. But let’s set up a Provocative Operation. PO: the parties each come with “a most reasonable” proposal and the judge decides what the “most reasonable” is.

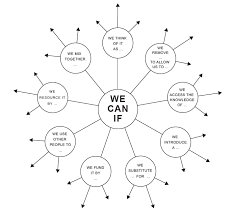

Design by overcoming either/or situations

Many situations present themselves as either / or situations. Even more often they are deliberately put this way. The aim is then to obtain clarity or certainty in complex situations, or to force people to make choices. It testifies to laziness to go along with this.

We should help refugees to get paid jobs, but at the same time the local unemployment is 50%. How would we provide jobs when there are no jobs at all? This is a quite hopeless situation.

However, the design question has an and/and-structure. In what circumstances could we provide refugees with jobs and reduce the local unemployment?

A good method to move forward to solutions is presented by Adam Morgan, Mark Barden in their book A Beautiful Constraint: How To Transform Your Limitations Into Advantages, and Why It’s Everyone’s Business.

Either/or situations also often occur in negotiation situations or in conflicts. Parties usually try to get their way through. A targeted design effort could help to reach a mutually acceptable agreement.

Pitfalls to Avoid

- Lack of focus. For example “we want to think about the future” or “we want to proactively anticipate social developments”. This is much too vague and too broad to be able to impose a focused effort.

- Don’t take a break. Of course you will never come to designs if you allow yourself to be ruled by the issues of the day. So you have to reserve time for a break.

- Discovering the cause of a problem is more important than ensuring that there is a solution that works.

- Negative Thinking that something can never work instead of putting everything on everything to ensure that it will work, then test

- Continue to work from one point of view or entry-point even though that gives an increasingly better – mostly: more detailed – but still unsatisfactory result.

Applications

Designing is an alternative to assessing or removing the cause like

solution to a problem. You can also combine them. One policy group can deal with a classical policy-analogous approach, another group could proceed with a design approach. Both groups could make use of an information group that provide facts and figures.

Conclusion

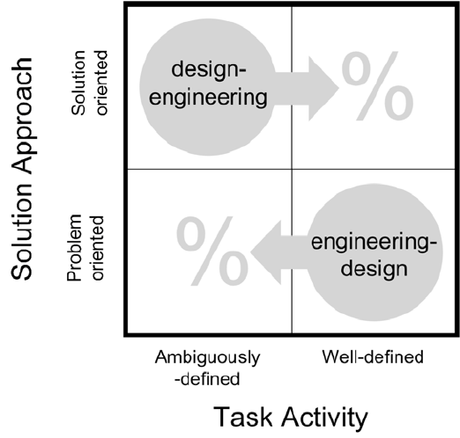

There is a difference between solving problems – removing the cause – and designing solutions. In the first case you act like a plumber. They are necessary and important. Bad plumbers are no good.

In the other case you are a creator who wants to make something new, possible.

Here more about Design Thinking versus Engineering in this post.