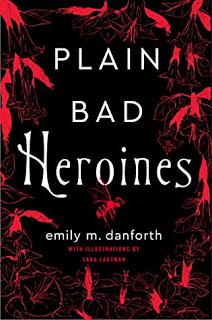

Emily M. Danforth’s Plain Bad Heroines (aided by beautiful illustrations by Sara Lautman) is a matryoshka doll of a story. Nesting – and what a great horror-inspiring verb that is – at its center is Mary MacLane’s first published book, originally titled I Await the Devil's Coming, but renamed by the publisher to the more socially palatable The Story of Mary MacLane. This 1901 sensation of autobiographical writing caused a craze at the time, especially among young girls, and inspired what we would now call a dedicated fandom. It is also the historical kernel of Danforth’s horror novel, and a delight of a starting point into the rabbit hole. MacLane, spending her youth in Montana like the author, later went on to lead a bohemian (and queer) life, writing more books and starring in the 1917 silent film Men Who Have Made Love to Me, in which the fourth wall to the audience is broken, which also seems fitting – in Plain Bad Heroines, an omniscient narrator often addresses the reader directly and comments further on the happenings in both informative and ironic footnotes. We find out that we are in a horror novel early into Plain Bad Heroines. In 1902, Clara and Flo are students at a Rhode Island boarding school called Brookhants School for Girls, founded and run by a couple that will star in another layer of this nesting doll. They have dedicated themselves to MacLane’s writing, identifying with her voice and her unconventional and rebellious disregard for what teenage girls are meant to strive for. They also find a horrible end soon after being outed – stung to death after stumbling into a nest of yellowjackets on the schoolgrounds. Wasps will continue to swarm and haunt the rest of the story like harbingers of impending doom. Predictably, MacLane’s writing, which has inspired the girls to overcome social conventions, now engenders a moral panic in their surroundings. The novel traces the particular individual book the girls read together back to the school’s founder Libbie Brookhants, for whom it functions like the tell-tale heart of a past betrayal of her current partner.

Emily M. Danforth’s Plain Bad Heroines (aided by beautiful illustrations by Sara Lautman) is a matryoshka doll of a story. Nesting – and what a great horror-inspiring verb that is – at its center is Mary MacLane’s first published book, originally titled I Await the Devil's Coming, but renamed by the publisher to the more socially palatable The Story of Mary MacLane. This 1901 sensation of autobiographical writing caused a craze at the time, especially among young girls, and inspired what we would now call a dedicated fandom. It is also the historical kernel of Danforth’s horror novel, and a delight of a starting point into the rabbit hole. MacLane, spending her youth in Montana like the author, later went on to lead a bohemian (and queer) life, writing more books and starring in the 1917 silent film Men Who Have Made Love to Me, in which the fourth wall to the audience is broken, which also seems fitting – in Plain Bad Heroines, an omniscient narrator often addresses the reader directly and comments further on the happenings in both informative and ironic footnotes. We find out that we are in a horror novel early into Plain Bad Heroines. In 1902, Clara and Flo are students at a Rhode Island boarding school called Brookhants School for Girls, founded and run by a couple that will star in another layer of this nesting doll. They have dedicated themselves to MacLane’s writing, identifying with her voice and her unconventional and rebellious disregard for what teenage girls are meant to strive for. They also find a horrible end soon after being outed – stung to death after stumbling into a nest of yellowjackets on the schoolgrounds. Wasps will continue to swarm and haunt the rest of the story like harbingers of impending doom. Predictably, MacLane’s writing, which has inspired the girls to overcome social conventions, now engenders a moral panic in their surroundings. The novel traces the particular individual book the girls read together back to the school’s founder Libbie Brookhants, for whom it functions like the tell-tale heart of a past betrayal of her current partner. Danforth traces the book – literally, and in terms of its influence – backwards and forwards in time. Forwards, it leads to literary wunderkind’s Merritt Emmons book The Happenings at Brookhands, which details the fate of Clara, Flo and a third student who came to a horrible end after being haunted by something that the book itself indirectly roused. Emmons’ book, completed at sixteen and for now without a follow-up, is now being adapted into a film. This adaptation becomes another doll, encapsulating both Merritt’s novel and what we have already learned about Clara and Flo – but we will later find out that the director, Hollywood horror genius Bo Dhillon, plans to build an even larger doll around Merritt and the two actors cast as the main characters. Inspired by found-footage horror films like The Blair Witch Project, Bo plans to not only film Merritt’s book, but also the production of the film itself, and the relationship between the writer and the two actresses, especially after they stumble into a complicated net of interpersonal drama. At the center of it is Harper Harper (again, a wink, this one maybe a little bit too much?), a rising young star, who, in a segment of the novel that reads most like a blossoming romance (a path it never quite goes down to, at least not unambiguously, even though there’s a lot of tragic romance in this), begins courting Merritt not just for insider information on the character she will be playing, but also more conventionally, because she really seems to like her a lot (and she is also conveniently in a non-monogamous relationship). Merritt, who enters Hollywood with the overwhelming sense of being in over her head, seems swept along with it the more Harper breaks down the walls of cynicism she’s built around herself, but then pulls back when the second actress enters the stage.

Audrey Wells, daughter of a 1980s scream queen who more recently has made headlines with a tragic accident and substance abuse issues, appears too inexperienced to be in a film that has a star like Harper Harper attached, and Merritt appears to dislike her on the spot, until that feeling slowly turns into something a whole lot more ambiguous. And this is my favorite part about the whole book – that everyone in it is queer, and that all the relationships always appear to be verging on something more, or something else, in much the same way in which the story itself appears to be straightforward until it veers into psychological horror. The director informs Audrey of his plans to secretly film the production of the film, the relationship between the three women, and to introduce elements of horror to that story – manufactured mysteries that will make the set appear haunted, except then of course his intention is overshadowed by the very real haunting of Brookhants, the one that has killed and driven to madness women before them, and may or may not have started with something called Spite Tower, a pointless structure that was erected to spoil the view of an independent woman who refused to move for the benefit of two brothers with great plans.

And if it hasn’t been clear so far – there are so many meta-levels to Plain Bad Heroines that it is almost impossible to mention them all. Danforth’s first was the raw The Miseducation of Cameron Post (a novel that I love more than almost any other, that I reread as soon as I finished it the first time, and was adapted two years ago into a great film that according to Danforth did not directly inspire the meta-story around the film-production of The Happenings at Brookhants). This book is entirely different, mainly because the narrator creates some distance between the reader and the characters. A very essential part of Cameron Post is Cam’s process of realising that she is gay, and finding ways to figure out what that means in both a remote location and in a time before the internet. For Cam, that means going to videostores and trying to figure out if the films are gay based on the blurb at the back (she does pretty well for small-town Montana, two of the films playing a more central role are Personal Best, a 1982 classic in which Mariel Hemingway plays a sprinter, and The Hunger, a 1983 vampire film starring Catherine Deneuve, Susan Sarandon and David Bowie). Later she has a tentative connection to the outside world through a friend and fellow swimmer, who sends her dispatches and mixtapes from the Pacific Northwest. As much as this is a very personal and raw book, now it also works as a time capsule of the 1990s (what would Cam have been like had she had Jamie Babbit’s But I’m a Cheerleader, a completely different approach to the conversion camp horror story, this one more camp but still tragic underneath).

Plain Bad Heroines is similar to that in the sense of diving deep into what it means to be young and different, and desperately trying to find something that reflects this experience. Clara and Flo find it in Mary MacLaine’s writing – an indication that a different life is possible, even if theirs end so early and so tragically – and Merritt finds it in their story, and that of the weird haunting of Brookhants, which is in a way another haunted manor story in the year of Bly. A place bears the wounds of its past – of two girls, stung to death, a third, driven to suicide via poisonous plant (one that, predictably, is later used to get high, always a good thing to do on haunted grounds), and that of founder Libbie and partner Alexandra Trills, which also ends badly. The novel shows women loving each other and making lives with each other – against societal conventions (the footnotes frequently refer to Boston marriages). The extension of this desire for representation is maybe between the reader and the three women who are watched being themselves, who become – wittingly or unwittingly – characters themselves in the director’s attempt to manufacture a found-footage film (and, because the layers never end, Merritt is writing her second book about the production of the film) – because in this horror story, everything is suddenly possible. What may have been subtext to never come to fruition – not just the obvious attraction between Merritt and Harper from the get-go, but also the immediate intense connection between Harper and Audrey through the characters they play, and the ambiguous change that happens between Merritt and Audrey – is text here (a text in which the three final girls are all in love or lust with each other), and only hindered by the fact that they are also in a horror story littered with bodies.