It was the joy. The sheer, uninhibited joy. That was my takeaway from watching Pelé.

If it can be said that playing a sport - any sport - could prove difficult, trying, or exhausting in the extreme, then observing and learning from a competitor such as Pelé was its own reward. He made the difficult seem doable, the trying easy, and the exhaustion mere child's play.

How many times have I witnessed this miraculously gifted athlete stumble, fall, and be set upon by the opposition? Yet, at nearly every interval, at every wrong turn or battle for dominance, Pelé would emerge triumphant - even if he did not score a goal.

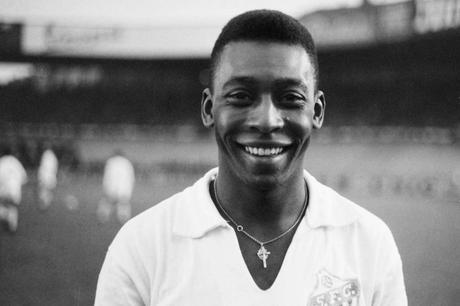

He would pick himself up, dust off the dirt and grass, and flash that thousand watt smile. "You see?" he appeared to be telegraphing to the throng of worried spectators. "There's nothing to it." Ah, but there was!

His native team, Santos of Brazil, made him a star player. When my family and I first laid eyes upon his sleek form, it would be one of Pelé's first appearances in the U.S.: an exhibition match with, of all people, Portugal's Eusebio, the only other Black player at the time to have reached the dizzying heights of World Cup Soccer stardom.

Back then, I had little knowledge of how futebol, or football as the Europeans called it, was played (I must have been all of 10 or 11 years of age). But I could sense the excitement that was building, the expectation that something spectacular was about to take shape. That's when I began to learn.

How I wish we had brought our camera. There were no iPhones or Androids back then. And the Polaroid was, financially speaking, still out of my reach. No amount of allowance money could have overcome that monetary deficit.

Still, the memory of seeing those tiny Black figures, from the bleachers at Downing Stadium in Manhattan's Randall's Island, was thrilling enough. Unmistakable in his white jersey and baggy shorts, the image of this five foot, eight or nine inch Brazilian celebrity remains imbedded in my brain.

When next we watched Pelé perform, for that indeed was what he was noted for, it was during the 1970 World Cup games in Mexico. Brazil beat England 1-0. Jairzinho, the tall and agile right winger, scored a marvelous shot - with Pelé's assistance, of course.

Knowing he could draw the opposition away from their stated positions, which would help Brazil to advance to the next round, Pelé pretended to be on the attack. Using his head, shoulders and hips to fool the defenders into thinking he was about to score, Pelé casually passed the ball to Jairzinho. He had no need to look over his shoulder. He just knew that Jairzinho would be there.

One could tell that instinct had played a large part in Pelé's methodological bag of tricks. And it worked, too. Nearly every time he tried it. But when it didn't, oh well. He would shrug it off and smile. There would be a next time.

He had mastered this and other techniques as a gangly child, back in his slum days of Tres Corações ("Three Hearts") where he grew up. His birth name was Edson Arantes do Nascimento, after his father, Edson Sr., himself a former soccer player whose career had been cut short by injuries. "Edinho," or Little Edson as he was then called, vowed he would make up the shortfall by becoming a soccer player as well. Which he did.

How he got the nickname "Pelé" is still a cause for speculation. The name itself means absolutely nothing. Which, if you stop and think about it, is so like the individual it describes. Without the accent over the second "e," the Brazilian-Portuguese word pele translates to "skin," which places emphasis on the first syllable. And on his skin. Yes, his skin. It was Black, his hair was wiry and short, but the smile was big and broad. His face encompassed an entire world of gains and losses, and of ups and downs.

His generosity on and off the field, his ability to see and sense where his teammates were at any given moment, was one of his most outstanding qualities. Sure, he could smack that ball in whenever he made up his mind to do so. And, like most scorers, he missed the goal mouth more times than he actually scored.

Did that upset him? Did he feel like hanging his head in shame? Of course, but he rarely showed it. "There's always next time," Pelé seemed to be saying. Shrugging his shoulders and showing off those pearly white eighty-eights to one and all, Pelé happily trotted off to try again. He never gave up trying.

His three seasons with the New York Cosmos gave me and many of his fans - Brazilian or otherwise - several more years of watching, learning and absorbing the master at work. How incredibly lithe he still seemed, how like a mini-computer his mind appeared to be as he invented new ways to stymie the opposition.

Sure, he had slowed down considerably from his youthful, carefree form. But the fans didn't mind. They wanted to see him play, period. Friction with other team members, especially the brooding "rock star" Giorgio Chinaglia, only made Pelé more determined to do his part for the cause.

I was present, along with my Uncle Daniel and over seventy-plus thousand fans, at Giants Stadium in the Meadowlands, for his farewell game on October 1, 1977. It would be against his former team, Santos. The circle Pelé started back in 1958, at his first World Cup in Sweden, was about to close. A new chapter would begin for him as an icon, a symbol, a marketing tool, as Minister of Sports in Brazil, and as a spokesperson and radio/television commentator for soccer.

His failings as a parent, his questionable financial dealings and other, more personal issues - all vied for further press coverage and equal time with past successes on the soccer field of dreams. All in all, through illness and, inevitably, through his passing, Pelé never stopped smiling.

That smile, that joy of having lived and played and won the game, stayed with him till the end. There would be no more next times, no more trying. The final whistle had blown.

Pelé had scored his last goal and has passed into legend.

Copyright © 2023 by Josmar F. Lopes