Loci and Spaces

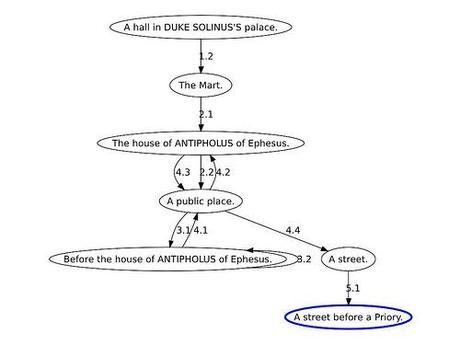

Roughly two months ago I put up a post on and article David Ramsay had done on plot structure in Shakespeare. He’d created graphs the depicted the movement of individual plays from one location to another, such as in this graph for Comedy of Errors:

Each node in such a graph represents a physical setting (a locus in my terminology) where action takes place. There are some loci where only one scene is set and other loci where several scenes occur. You can follow the action through a play by starting at the top (in this case) and following the edges in order, where the edges are labeled by act and scene.

Ramsay noted that different plays displayed different patterns, and explained a procedure by which, with the help of a graduate student, Bei Yu, he was able to classify the plays more or less in the traditional four categories – comedies, histories, tragedies, and romances – on the basis of the graphs alone, with no information about what actually happens at the various loci.

What do we make of THAT? Ramsay didn’t know. Nor do I, though I suspect the loci might not be ‘mere’ physical settings, but that they might have specific thematic valences or affordances.

I’ve just come across an article, Forces and Spaces – Maupassant, Borges, Hemingway, Toward a Semnio-Cognitive Narratology, by Per Aage Brandt that suggests exactly that, though in conjunction with stories by de Maupassant, Borges, and Hemingway, rather than Shakespeare plays. Here’s a sentence from the abstract:

There is, I postulate, a canonical set of narrative spaces, each encompassing and contributing a significant part of the meaning of a story. The model distinguishes four such spaces, which are typically also staged as distinct locations; an initial conditioning space, a catastrophic space, a consequence space, and a conclusion space.So, can the nodes in Ramsay’s Shakespeare diagrams be classified according to those four types? I don’t know, but I suspect that something like that may well be going on.

Sentiment and Periodicity

Matt Jockers has an interesting post in which he uses sentiment analysis to track plot movement. The basic idea is there in this short video of Kurt Vonnegut, which he embedded in his post:

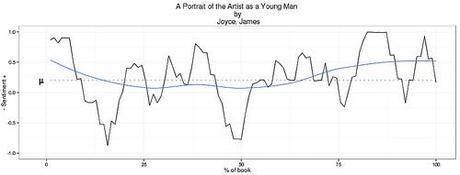

Jockers posted plots of several texts. Here’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man:

As we go from the left to the right we’re moving from the beginning toward the end. The upper end of the Y axis is positive sentiment while the lower end is negative.

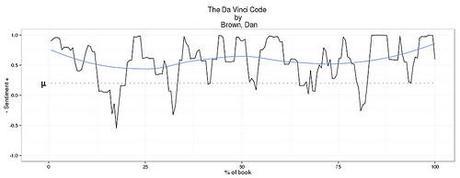

Here’s the graph for Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code:

Jockers’ comments:

Notice how much more regular the fluctuations are. This is the profile of a page turner. Notice too how the more generalized blue trend line hovers above neutral in terms of its emotional valence. Dan Brown never lets the plot become too troubled or too much of a downer. He baits us and teases us with fluctuating emotion.OK, though, as I eyeball the chart for Portrait, I can (almost) see an underlying periodicity that’s obscured by the larger movements.

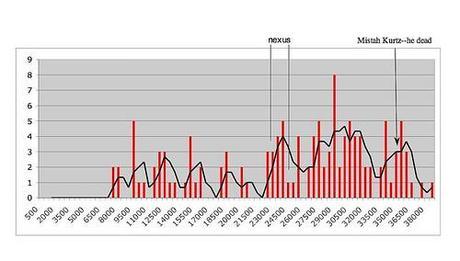

Which brings me to a little work I did on Heart of Darkness. I was interested in the occurrences of the name “Kurtz.” So I went through the text, noted each occurrence, and counted the number of occurrences in each 500 word bin (the text has roughly 38,000 words), as I explain in Periodicity in Heart of Darkness. Here’s the chart:

Kurtz isn’t even mentioned until roughly 8,000 words in. And then he’s only talked about; he doesn’t appear in the story until much later. From that point on the name’s occurrence is roughly periodic, though the baseline goes up a bit over halfway through the text. That happens at the long paragraph I’ve called the nexus, where we learn Kurtz’s background.

Kurtz isn’t even mentioned until roughly 8,000 words in. And then he’s only talked about; he doesn’t appear in the story until much later. From that point on the name’s occurrence is roughly periodic, though the baseline goes up a bit over halfway through the text. That happens at the long paragraph I’ve called the nexus, where we learn Kurtz’s background.

It would be interesting to do a sentiment analysis of this text and see how that curve would overlay the Kurtz curve. I don’t know how that would go, but I’d be looking for changes in sentiment that coincided with the major features of that curve, the onset of “Kurtz”, the nexus (roughly halfway), and Kurtz’s death (marked in the chart by the phrase “Mistah Kurtz–he dead”).

More generally, I think there’s a lot of work to be done here. Surely sentiment can be tracked in a more fine-grained way than just positive and negative. What else can be tracked?

There’s gold in them thar hills!

Ben Goertzel on Pattern

I’ve just found out that an AI researcher named Ben Goertzel has developed a general philosophy of patterns. There’s a book, which I’ve not read: The Hidden Pattern: A Patternist Philosophy of Mind (2006). The book has an appendix in which Goertzel outlines a mathematical formulation of his theory. The math is beyond me, but I note that Goertzel defines the concept of a pattern with respect to a procedure enacted in some domain of entities (pp. 366-367), which is more or less what I did in my working paper on patterns.

If you don’t want to go for the book, you can download a paper that sets out some of the basic ideas: Patterns, Hypergraphs and Embodied General Intelligence (PDF).