Chitral, Pakistan

My husband’s Aunt Carolyn traveled to Pakistan in the 1970's. The following is an excerpt from her memoir of her travels and is the second half of her report of her trip to the Kalash Valley.The descent into the Kalash Valley was uneventful. We proceeded to a rest house where we ate a box lunch from the hotel with other men who had come to the village of Birir to attend the festival for which this valley is famous.

The Kalash tribesmen are non-Moslem and are known as Kafir Kalash which means “wearer of black robes.” There are about three thousand of this tribe in the valleys of south Chitral, in isolated areas between the lower peaks of the Hindu Kush. Primarily farmers, they maintain their ancient culture and religion. The men distinguish themselves from non-Kalash by wearing the Chitral woolen caps decorated with feathers and bells. (This traditional dress is reserved for festivals.) The women wear black cotton gowns and picturesque headgear made of black material covered with shells and buttons, which, I was told, weighs from three to six pounds. Their ethnic origin is uncertain, but legend alleges that soldiers from Alexander the Great’s legions marched through these valleys in the fourth century B.C., and left behind traces of Greek heritage.

It was fascinating to watch the dancing of the spring festival. Lines of women, arms about each other’s shoulders, move in slow rhythm to form a circle. The men also form into a circle and move with intricate steps to the music of drums and flutes. The shuffle of their feet in the dust, their slowly moving bodies were almost hypnotic. Onlookers gathered small branches of green leaves to wave, and some children gave me my share. I was invited to participate in the dancing, which is considered a mark of friendliness.

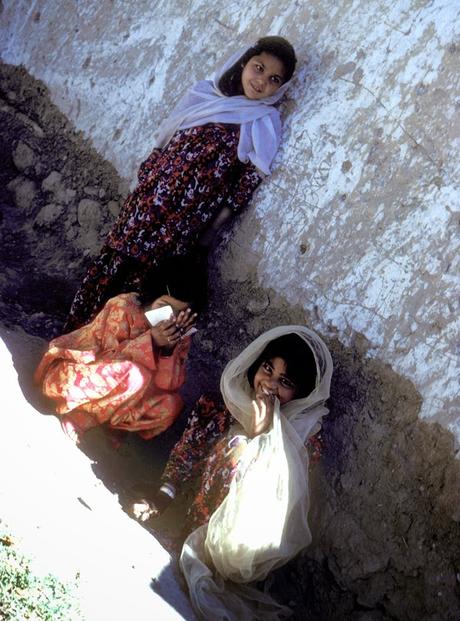

Chitral girls

We left Birir in the Kalash Valley early as we had to cross that same rugged mountain road again, and no night driving is allowed anywhere in Chitral. When we reached the mud slide area the men were still working, and, in fact, had torn up our bypass. We had to wait until the fill-in dirt, propped up by rocks at the edge, was wide enough for our jeep to pass. The surface was quite soft, so when another jeep from the opposite direction approached, we were glad to let them try the repaired road first. When I saw the rocks sag at the outer edge, I said, “This is where I walk.” I think the driver did not like to be abandoned after the others followed me out, but he drove safely across. We climbed in and were on our way. I sat on the outside this time with one foot braced against the front dashboard, and my knee was half hanging out. We returned safely to river level.About five miles from “home” the jeep stalled. No more gas! The only thing was to wait for another jeep to come along this lonely road and to beg some gasoline. After our dusty ride, the boys left to go down to the river to wash their faces. I got out to shake as much dust as possible from my clothes and just wait. The boys went on to visit a nomad camp near the river. Soon they returned with a bowl of goat’s milk “for your refreshment.” In the first place, I do not like goat’s milk, but when I saw a large fly swimming in the middle of the bowl, that did it! I felt uncomfortable about refusing their hospitality. All along, I had tried to be a good American and to adapt to foreign ways and unfamiliar food, but this was too much. As politely as possible, I told the one English-speaking man to tell the nomads that I appreciated their hospitality, but that we did not drink milk. After some further wait, the billowing dust heralded an approaching jeep. The boys arranged for gas from their tank, and, by borrowing a tea kettle from the nomad family, poured enough gas into our tank to get us home. How tasty the Nomad’s tea must have been for some time!

Perhaps the original intrepid tourist was Carolyn T. Arnold, my husband’s aunt. A single school teacher in Des Moines, Iowa, she began traveling abroad when she was in her forties, beginning with a bicycling trip through Ireland in 1952. She went on from there to spend a year as a Fulbright Exchange Teacher in Wales, to more trips to Europe and beyond, and eventually became a tour leader, taking all her nieces and nephews (including my husband Art) on her travels. When she retired from teaching, she wrote of her experiences in a memoir called Up and Down and Around the World with Carrie. Today, as I read of her travels, I marvel at her spirit of adventure at a time when women did not have the independence they do today. You can read of some of her other adventures in these posts on this blog: October 21, 2013; October 7, 2013; July 29, 2013.March 10, 2014, February 9, 2015.