Book Review by Chris Hopkins.

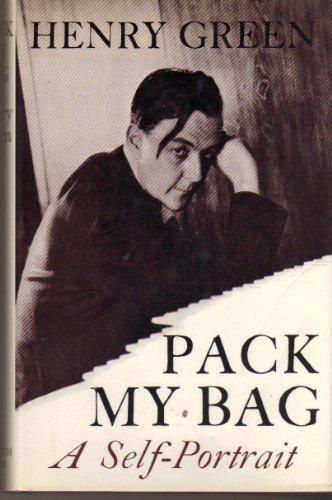

Henry Green (1905-1973) was the pen name of Henry Yorke, a contemporary of writers such as Elizabeth Bowen, Graham Greene, Anthony Powell and Evelyn Waugh. All of these novelists and many other writers and critics have thought Green one of the greatest fiction-writers of his time, but he never commanded quite the readerships they did. In 1940 he had published three novels: Blindness (1926), Living (1929) and Party-going (1939), still often regarded as his most extraordinary works (though I would see his six war-time and post-war novels as equally idiosyncratic, original and insightful). In 1940 he was thirty-five years old, and though there were then and since some ‘early’ autobiographies by celebrities, it was not that common for a writer to look back over their life so soon. Green is very explicit throughout Pack my Bag about how he has come to write it:

I WAS BORN a mouthbreather with a silver spoon in 1905, three years after one war and nine before another, too late for both. But not too late for the war which seems to be coming upon us now and that is a reason to put down what comes to mind before one is killed, and surely it would be asking much to pretend one had a chance to live. That is my excuse, that we who may not have time to write anything else must do what we now can. If we have no time to chew another book over we must turn to what comes first to mind and that must be how one changed from boy to man, how one lived, things and people and one’s attitude. All of these otherwise would be used in novels, material is better in that form or in any other that is not directly personal, but we I feel no longer have the time (Vintage Classics, p.1).

He is writing an autobiography now while still alive to write it, since he does not think the prospects of surviving the war are strong (in fact he began writing it in 1938, so like many others was justifiably anxious for some time before the actual outbreak of war). Green feels that autobiography is something which can be written more quickly than a novel, or rather that its material may be more immediately available, though he would rather have time to develop the stories of his own life into the less personal form of a novel. The quotation is the first paragraph of Pack My Bag and as well as suggesting something of the melancholy of the book, its perspective on early life from what seems an almost certain early end-point, it also shows that though an autobiography, it will draw on the experimental and very individual style which Green had developed in his three novels thus far. The style in this opening passage is less unusual than some of the writing later in Pack My Bag, but there are enough peculiarities to suggest Green’s individuality (something which should surely be key in an autobiography of a writer). The slightly though not wildly unusual word order asks that the reader progresses carefully, not skimming or assuming ready-made meaning, to decode exact and nuanced perceptions. It is in short a modernist style, though not one that is excessively demanding. The opening phrase strikingly delivers something fresh by coining a new word and yet also by recasting a ready-made phrase: ‘I WAS BORN a mouthbreather with a silver spoon’.

One of the great technical and artistic achievements of Pack My Bag is to highlight a sense of the freshness, of the presentness, of the nowness, sometimes of the painfulness of childhood, youth, early life as it was, with a somewhat separated sense of the retrospective which every autobiography must always contain. Green uses his style to present childhood episodes and feelings as near as possible to how they were experienced immediately, rather then re-interpreted later. Take for example, his representation of the officially implanted childhood guilt at school about having any private thoughts whatsoever:

When we left our nurseries, and the gardens or lumber-room we could hide in we found at school no corner even in the fields where we could be alone without having transgressed by being there and that was something we were too afraid to do at first. We were almost prisoners from ourselves and were told, a little later on perhaps, there were no thoughts or feelings we ought to have which we could not share and that if there were things we could not say then it was a crime. And so it became criminal to be afraid. And so it will be again, quite soon now I suppose (p.11).

One notes the return to the present at the end of the passage, where Green supposes that the experience of the forthcoming war will be similar to this allegedly totalitarian culture of school (I think he is imaging not only the prospect of life under Nazi occupation, but also, and perhaps disproportionately, life if conscripted into the Army).

He also is not afraid to incorporate without hesitation theoretical reflection on the impossibility of undistorted memory in autobiography:

Most people remember very little of when they were small and what small part of this time there is that stays is coloured it is only fair to say, coloured and readjusted until the picture which was there, what does come back, has been overpainted and retouched enough to make it an unreliable account of what used to be. But while this presentation is inaccurate and so can no longer be called a movie, or a set of stills, it does gain by what it is not, or, in other words, it does set out what seems to have gone on; that is it gives, as far as such things can and as far as they can be interesting, what one thinks has gone to make one up (pp.2-3).

Another Greeenesque idiosyncrasy is to use extended metaphors which blur the distinctions between the literal and metaphorical so that a metaphorical figure apparently introduced to comment on a kind of experience enters into the description of the experience itself:

AS WE LISTEN to what we remember, to the echoes, there is no question but the notes are muted, that those long introductions to the theme life is to be, so strident so piercing at the time are now no louder than the cry of a huntsman on the hill a mile or more away when he views the fox. We who must die soon, or so it seems to me, should chase our memories back, standing, when they are found, enough apart not to be too near what they once meant. Like the huntsman, on a hill and when he blows his horn, like him some way away from us (p.92).

While Green’s background, as he declares in the text’s first sentence, was very privileged, it was also as represented in this deeply reflective commentary on it, experienced as traumatic in a sustained way. Some episodes were painful in a particular way – including the occasion when his headmaster told him that a telegram had arrived reporting that both his parents had been severely injured in a (railway?) accident in Mexico, and that though currently alive there was no chance of them surviving (his father had highly profitable interests in Mexican Railways and visited Mexico every other year). It was arranged that Henry should go to his grandmother’s alone on the train next day, but his distress was further increased firstly by reading in the Times at breakfast next day a similar statement about his parent being alive yet having no prospect of surviving, and secondly by telling his headmaster something ‘genuine’ (p. 94) – that he did not know how to feel about his parents’ imminent death. When he arrived at his grandmother’s house, he was greeted by an uncle who reported that in fact his parents were not that severely injured and would survive and return home in due course. Underlying this specific suffering was the prolonged training at his prep and public school (Eton) in the bad form of in any way expressing emotion, to which the autobiography frequently refers.

This experience of school perhaps impacted on Green’s experience of Oxford where he soon fell into a pattern of heavy drinking such that he was never sober, and felt he was losing his reason. He did however (not necessarily a common experience among undergraduates of his class) develop a respect for the scholarship of his tutors, and this eventually brought him round. He did not though complete his degree (in English), but left after two years to go and work on the shop floor of his father’s factory (Pontifex Ltd, which made highly profitable beer-bottling machinery). This experience informed his wonderful (quasi?) proletarian novel Living of 1929, which did indeed see ordinary working-class life as infinitely more authentic than upper-class life (though the novel is in no way naive about economic constraints and lack of opportunity). Indeed, Pack My Bag itself offers a nuanced commentary on the good the works do Henry without making it too much ‘proletarian pastoral’ in genre:

The men themselves, the few that bothered to think about it, were of the opinion I had been sent there to be punished. They can take it from me theirs is one of the best ways to live provided that one has never been spoiled by moneyed leisure which is not as they would put it, something better (p. 154).

I think this is a complex and moving autobiography which fully incorporates the peculiar circumstances of its composition and offers significant insights into the lasting pain of certain upper-class and public-school cultures in this period as understood by an author who could simultaneously create and analyze. I absolutely recommend reading it. As Green tells us in Pack My Bag, he has already volunteered to join the AFS (Auxiliary Fire Brigade) which was hugely to expand the established Fire Brigades in the event of war and the expected bombing raids. He also there expresses the anxiety that he will be nevertheless conscripted into the Army which he fears (he had refused with considerable negative consequences to participate in the Eton Officer Training Corp or OTC). In fact he served in the AFS in London with great courage throughout the War, including in the months of the Blitz. One of his wartime novels, Caught (1943) gives an extraordinary account of life in the wartime AFS, though naturally, being by Henry Green, it pursues many other complexities too.