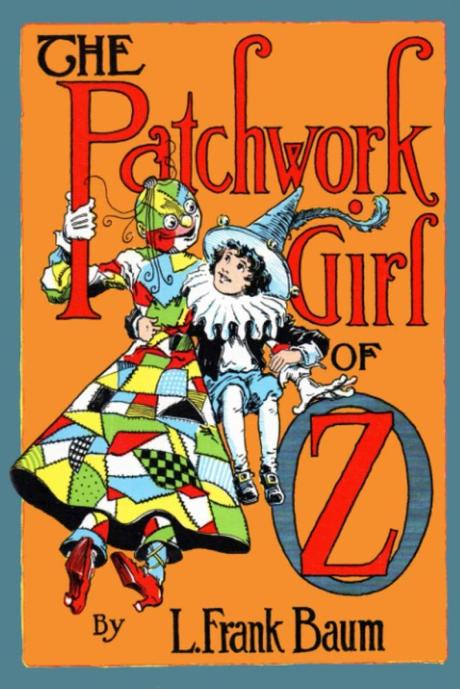

The Patchwork Girl is easily one of my favorite Oz characters, and there are so many things I love about this book. It’s interesting to me that after Book 6, The Emerald City of Oz, where Baum made his best attempt to end the series (he literally made Oz disappear), he comes back with one of his most complete, entertaining, and coherent stories. This book is a worthy entry to the second half of the series and quite different from the previous stories. There’s plenty to talk about here, but first see this post from Lory at Entering the Enchanted Castle for her take on the book.

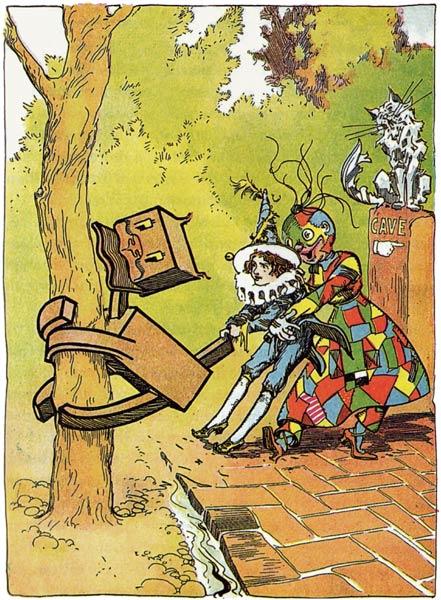

Book 7 begins with Ojo, a young boy, having a mostly one-sided conversation with his Uncle about their lack of food. Unc Nunkie only says about one word at a time and is known as “the Silent One”. Ojo and his uncle live in a secluded wood but will soon be forced to leave to find sustenance. Their nearest neighbor is Dr. Pipt, the Crooked Magician. Their visit to Dr. Pipt results in both creation and tragedy, and sets Ojo on a quest across Oz to save his uncle.

Baum writes with more emotion in this book than in any of his other books. His characters are typically brave or fearful or in need of something, but in this book Ojo’s love and desolation for his uncle leap off the page, making him one of the most fully developed characters in the Oz stories (in contrast, Dorothy may miss or worry about her family but she’s never really afraid).

Then Ojo went to Unc Nunkie and kissed the old man’s marble face very tenderly.”I’m going to try to save you, Unc,” he said, just as if the marble image could hear him; and then he shook the crooked hand of the Crooked Magician, who was already busy hanging the four kettles in the fireplace, and picking up his basket left the house.

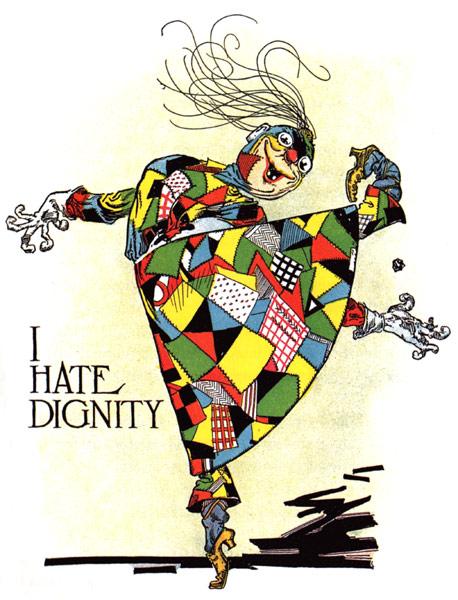

As the title character, Scraps is full of life and emotion, even without a heart (as the Scarecrow mentions, he’s without a heart too and does just fine). It’s her brains that are special. She was meant to be just a servant to the Magician’s wife, who wanted her to have only just enough brains to do housework and obey orders. Ojo, however, sees great unfairness in that, and behind everyone’s back he adds to Scraps’ brains the qualities of cleverness, judgment, courage, ingenuity, amiability, learning, truth, self-reliance, and poesy.

Throughout the book, everyone reacts to Scraps, whether they think she’s charming, hilarious, brilliant or crazy – she’s never boring. There’s a focus on her appearance that I found a little tiring, but I think it’s also Baum’s way of commenting on the subjectivity of beauty (and maybe its lack of importance). Baum’s women are usually depicted as traditionally beautiful, particularly in Neill’s ethereal illustrations. Scraps is notably the opposite of that.

The Woozy is another of my favorite Oz characters, from his kindness and patience (he only gets angry if you yell “Krizzle-Kroo”) to his not-so-terrible growl. My cats often remind me of the Woozy; they have these tiny little meows but they’re sure they are terribly ferocious.

This book combines all the things Baum is known for – satire, adventure, fantastic worlds and characters, and of course wordplay. From terrible puns and jokes to poetry and songs, Baum reminds us that words are important. Ojo is known as “Ojo the Unlucky” and he blames his misfortunes on the name — but during his adventures he’s constantly reminded of how many ways he’s lucky, and how luck is simply a matter of seeing the positive.

Significantly, this book has a strong statement from Baum on the importance of law and the misuse of criminal punishment. When Ojo is arrested, he is taken to a prison that is a beautiful house full of books and games, a kindly caretaker and good food. Ojo asks how this can be punishment.

“We consider a prisoner unfortunate. He is unfortunate in two ways—because he has done something wrong and because he is deprived of his liberty. Therefore we should treat him kindly, because of his misfortune, for otherwise he would become hard and bitter and would not be sorry he had done wrong. Ozma thinks that one who has committed a fault did so because he was not strong and brave; therefore she puts him in prison to make him strong and brave. When that is accomplished he is no longer a prisoner, but a good and loyal citizen and everyone is glad that he is now strong enough to resist doing wrong. You see, it is kindness that makes one strong and brave; and so we are kind to our prisoners.”

This image of sad little Ojo being tenderly cared for by his jailor is one that stayed with me as I went through law school and afterwards.

Finally, in the outcome of Ojo’s quest, we see an instance of moral absolutism that greatly troubled me when I was young. The Tin Woodman is so soft-hearted he can’t allow harm to be inflicted upon a single creature. But in practice that means he’s also willing to condemn Unc Nunkie to a horrible fate (this reminded me of Ozma’s stance in the last book, where she was unwilling to fight for her people but willing to let them be captured and enslaved). While I could see his point, I never quite forgave the Tin Woodman for his callousness towards Ojo.

Rereading this book, there were some characters, illustrations, and songs that made me uncomfortable as they convey racial stereotypes common to the time. There’s the description of Scraps as a “slave” and her often exaggerated features. There’s a song the phonograph plays that is clearly minstrel music (some of the words were changed in my newer edition but I remember them). And there are the Tottenhots, which are clearly drawn as stereotypical Africans. Of course, this book was published in 1913, and taken in context, Baum clearly supports Scraps’ emancipation and admires her just as she is. (In contrast, I was unsettled by the treatment of the Glass Cat at the end of the book. However vain and heard-hearted she was, I didn’t like that Ozma and the Wizard replaced her brains and made a pet out of her.)

A final thing I noted, which I didn’t notice as a child, was the use of radium in the Horner village. The Horners mine the radium and use it to decorate their homes and as medicine. “No one can ever be sick who lives near radium.” In the time Baum wrote this, people believed radium would cure everything. We know now, of course, that people exposed to radium suffered horribly.

I hope you’re reading along with us, and if not I hope you’ll be inspired to give this book a read. If you do, please let me know what you think.