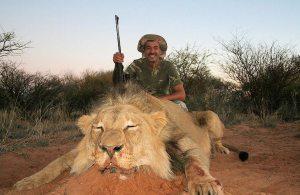

In July 2015 an American dentist shot and killed a male lion called ‘Cecil’ with a hunting bow and arrow, an act that sparked a storm of social media outrage. Cecil was a favorite of tourists visiting Hwange National Park in Zimbabwe, and so the allegation that he was lured out of the Park to neighbouring farmland added considerable fuel to the flames of condemnation. Several other aspects of the hunt, such as baiting close to national park boundaries, were allegedly done illegally and against the spirit and ethical norms of a managed trophy hunt.

In July 2015 an American dentist shot and killed a male lion called ‘Cecil’ with a hunting bow and arrow, an act that sparked a storm of social media outrage. Cecil was a favorite of tourists visiting Hwange National Park in Zimbabwe, and so the allegation that he was lured out of the Park to neighbouring farmland added considerable fuel to the flames of condemnation. Several other aspects of the hunt, such as baiting close to national park boundaries, were allegedly done illegally and against the spirit and ethical norms of a managed trophy hunt.

In May 2015, a Texan legally shot a critically endangered black rhino in Namibia, which also generated considerable online ire. The backlash ensued even though the male rhino was considered ‘surplus’ to Namibia’s black rhino populations, and the US$350,000 generated from the managed hunt was to be re-invested in conservation. Together, these two incidents have triggered vociferous appeals to ban trophy hunting throughout Africa.

These highly politicized events are but a small component of a large industry in Africa worth > US$215 million per year that ‘sells’ iconic animals to (mainly foreign) hunters as a means of generating otherwise scarce funds. While to most people this might seem like an abhorrent way to generate money, we argue in a new paper that sustainable-use activities, such as trophy hunting, can be an important tool in the conservationist’s toolbox. Conserving biodiversity can be expensive, so generating money is a central preoccupation of many environmental NGOs, conservation-minded individuals, government agencies and scientists. Making money for conservation in Africa is even more challenging, and so we argue that trophy hunting should and could fill some of that gap.

Nonetheless, there are many concerns about trophy hunting beyond the ethical that currently limit its effectiveness as a conservation tool. One of the biggest problems is that the revenue it generates often goes to the private sector and rarely benefits protected-area management and local communities sharing habitats with biodiversity. It can also be difficult (but not impossible) to determine ‘sustainable’ offtake rates — measuring just how many and what kind of individuals can be removed from a population without exacerbating extinction risk. Some forms of trophy hunting have debatable value for conservation, such as ‘canned lion hunting’, where lions are bred and raised in captivity only to be shot eventually in specially made enclosures. In such cases, there are no incentives generated for the conservation of natural habitats and other biodiversity.

At the same time, opposing trophy hunting as a form of sustainable use could end up being worse for species conservation. Financial resources for conservation, particularly in developing countries, are limited. As such, consumptive and non-consumptive uses of biodiversity are both needed to generate funding. Without such benefits, many natural habitats would otherwise be converted to agricultural or pastoral uses that have a decidedly lower benefit for native biodiversity.

Likewise, trophy hunting can also have a smaller carbon and infrastructure footprint than ecotourism, and generate higher revenue from a lower volume of users. Hunting can also lead to larger wildlife populations that by proxy have a higher resilience to extinction, because hunter clients specifically desire them. This contrasts with ecotourism where the presence of a few individual animals can maximise profits.

To address some of the concerns about trophy hunting and to enhance its contribution to biodiversity conservation and the benefit to local people, we propose twelve prescriptions. To make these prescriptions more relevant to decision makers, we have summarized them according to the guiding principles on trophy hunting promoted by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, which is the world’s oldest and largest global environmental organization.

- Mandatory levies should be imposed on safari operators by governments so that they can be invested directly into trust funds for conservation and management;

- Eco-labelling certification schemes could be adopted for trophies coming from areas that contribute to broader biodiversity conservation and respect animal welfare concerns;

- Mandatory population viability analyses should be done to ensure that harvests cause no net population declines;

- Post-hunt sales of any part of the animals should be banned to avoid illegal wildlife trade;

- Priority should be given to fund trophy hunting enterprises run (or leased) by local communities;

- Trusts to facilitate equitable benefit sharing within local communities and promote long-term economic sustainability should be created;

- Mandatory scientific sampling of hunted animals, including tissue for genetic analyses and teeth for age analysis, should be enforced;

- Mandatory 5-year (or more frequent) reviews of all individuals hunted and detailed population management plans should be submitted to government legislators to extend permits;

- There should be full disclosure to public of all data collected (including levied amounts);

- Independent government observers should be placed randomly and without forewarning on safari hunts as they happen

- Trophies must be confiscated and permits are revoked when illegal practices are disclosed

- Backup professional shooters and trackers should be present for all hunts to minimise welfare concerns.

Without greater oversight, better governance and evidence-based management, we fear that the trophy-hunting polemic will continue to the detriment of biodiversity, hunters and local communities. Adopting our prescriptions could help avoid this.

Enrico Di Minin & CJA Bradshaw