Some performers, like Ibrahimovic, are not ensemble players—you train the spotlight on them and hope for the best. No one who knows the 26-year-old Argentine-born Italian striker Pablo Daniel Osvaldo from the diverse appearances he has made with Espanyol over a couple of years would put him in that category. Yet at the Knitting Factory that is now Luis Enrique’s Roma, a festival of protracted ball possession which consists of ingenious variations of long duets, either in the form of rapid rolls or controlled wind-downs, with as many partners as one can find on the attacking front, he emphasized his theatrical inclinations. Looking vaguely like Johnny Depp, with yellow/black sunglasses, Eric Dolphy-esque hats off the pitch, and a long-cropped dark palette of hair, Osvaldo closes each goal with a gunshot whack to the terraces; while waiting for a killer-pass, he attends his associates’ forays with physical, rudimental support—of the kind that once made the tactical fortune of Del Vecchio—and then departs for the realm of soccer Dada in a series of gestures, anarchic and funny, that transport the viewers into the grateful tittering of be bop saxophones. Boring he is not.

He is uncanny with both feet, snapping time along until he tires of it and puts on the stage apron, like he did most memorably against Lecce on November 21, 2011 with his amazing overhead kick (wrongly disallowed). He can keep the center-backs busy like a tamburine-boy marches in a parade; he can keep them worried to a point of unholy aggression. Sometimes his headers look like the drummer sticks in a duel of cowbells—they are triplets, four-beat, or no beat. The fact that he managed an average of at least a goal every two matches also seems to confirm his fancy for two-beat patterns.

Among his partners, Lamela works in middle range, providing a respite of modulated lyricism; Miralem Pjanic, by contrast, is roundly boppish, a modern play-maker with a bit of Albert Ayler’s penchant for split-tones and squeals and a robust dose, to remain in jazz, of David Murray’s raging individualism. While Pjanic’s best pieces are architectural, Osvaldo’s melody is melancholic, like a waltz deeply embedded in the era of silent movies. (Here the Johnny Depp connection comes at handy: a uniquely talented actor whose finest hour came about when he did not speak.) Osvaldo is raising an intense fascination in Serie A, like a flamboyant diva of the 1920s. Enrique’s campaign of recruiting has wisely found in him, I believe, a touch of seemingly peripheral, retrograde nostalgia.

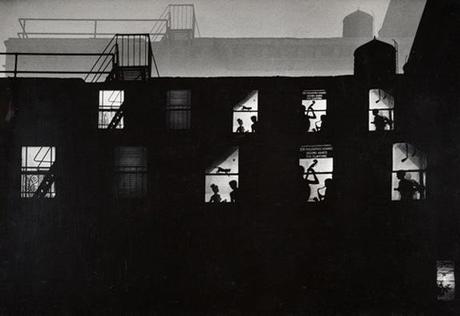

W. Eugene Smith, Jazz Loft, ca. 1959

Auguries, brio, and wounds will dry out one day, but Osvaldo will still be remembered as a whirling samurai with a reddish silk kimono and a wrinkled head-dress of the Kyoto style: a striker who fights with single sword-strokes to pierce the breast, and fallen bamboo-blades stained with bloody blossoms. A silent-era version of Kurosawa’s Rashomon, Osvaldo seems at times to pay homage to Charlie Chaplin’s formidable meditation on dance, loneliness, and Soviet-style montage. He belongs, it cannot be denied, to the category of one-shot actors—among them, Brando’s One-Eyed Jacks, Peter Falk’s police detective in the Columbo series, Laughton’s Night of the Hunter, and Cary Grant’s betrayer in Hitchcock’s To Catch a Thief. Roma’s score, being a work-in-progress, struggles to leave the registers of bass clarinet and achieve the vibrancy of drums and marimba that would be necessary to Osvaldo to flourish, but that is left to Luis Enrique to figure out. ♦