Mary Nimmo Moran, "'Tween the Gloamin' and the Mirk, When the Kye Come Hame"Etching, 1883

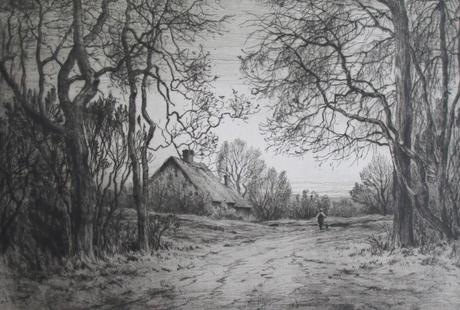

Mary Nimmo Moran, "'Tween the Gloamin' and the Mirk, When the Kye Come Hame"Etching, 1883 Henry Farrer, Winter EveningEtching, 1883

Henry Farrer, Winter EveningEtching, 1883 John Austin Sands Monks, TwilightEtching, 1883

John Austin Sands Monks, TwilightEtching, 1883Of the three twilight scenes above, that of Mary Nimmo Moran is my favorite. Despite the Scottish title, the scene is on Long Island, where Thomas and Mary Nimmo Moran habitually spent their summers.

Kruseman van Elten, The Deserted MillEtching, 1883

Kruseman van Elten, The Deserted MillEtching, 1883 R. Swain Gifford, The Mouth of the ApponigansettEtching, 1883

R. Swain Gifford, The Mouth of the ApponigansettEtching, 1883 James D. Smillie, At Marblehead Neck(also known as A Bit at Marblehead Neck)Etching, 1883

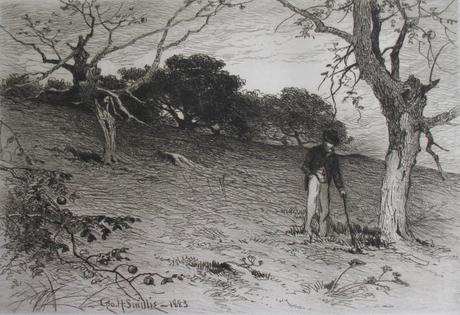

James D. Smillie, At Marblehead Neck(also known as A Bit at Marblehead Neck)Etching, 1883 James Craig Nicoll, The Smugglers' Landing PlaceEtching, 1883

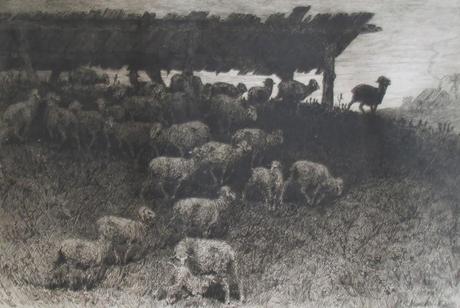

James Craig Nicoll, The Smugglers' Landing PlaceEtching, 1883 George H. Smillie, An Old New England OrchardEtching, 1883

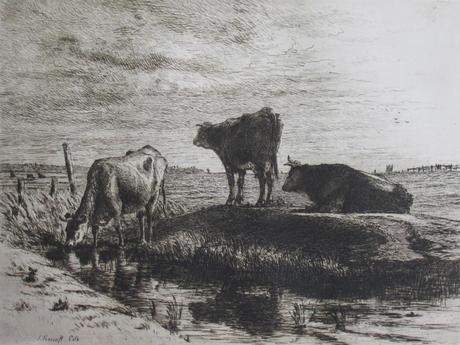

George H. Smillie, An Old New England OrchardEtching, 1883 J. Foxcroft Cole, The Three CowsEtching, 1883

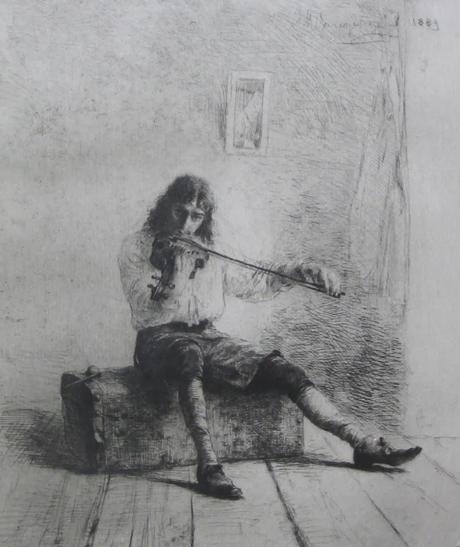

J. Foxcroft Cole, The Three CowsEtching, 1883Original Etchings by American Artists shows a snapshot of American printmaking at a crucial time; all of the etchings were made especially for this work, and many are dated 1883 in the plate. The artistic and technical skill on display is very impressive, even if Koehler’s insistence that each etching is a masterpiece needs to be taken with a pinch of salt. Impressionism hasn’t yet made any impact, and the key influence on the American landscapes, which predominate, is the plein-air Barbizon School. There are a couple of whimsical subjects: Church’s take on an Aesop fable and Gaugengigl’s faux-Meissonier fiddler. There are also four European scenes, one in Florence and one in Venice that have been removed, plus scenes in London and the Hague by Platt and de Haas. Of these, Platt's Whistler-esque scene of barges on the Thames at Woolwich seems to me particularly noteworthy.

Frederick Stuart Church, The Lion in LoveEtching, 1883

Frederick Stuart Church, The Lion in LoveEtching, 1883 Ignaz Marcel Gaugengigl, And Drive Dull Care AwayEtching, 1883

Ignaz Marcel Gaugengigl, And Drive Dull Care AwayEtching, 1883 Charles Adams Platt, Canal Boats on the ThamesEtching, 1883

Charles Adams Platt, Canal Boats on the ThamesEtching, 1883 Mauritz Frederick Hendrik de Haas, Fishing Boats on the Beach at ScheveningenEtching, 1883

Mauritz Frederick Hendrik de Haas, Fishing Boats on the Beach at ScheveningenEtching, 1883There are also three plates of particular interest for American social life and culture rather than landscape. Frederick Dielman’s The Mora Players, shows Italian immigrant children playing the ancient finger-counting game of mora or morra, in which the winner is the one who correctly guesses the total number of fingers simultaneously displayed by the two players. Koehler writes, “Italian bootblacks playing ‘mora,’ and yet a thoroughly American scene, enacted on a New York sidewalk!”

Frederick Dielman, The Mora PlayersEtching, 1883

Frederick Dielman, The Mora PlayersEtching, 1883 Thomas Waterson Wood, His Own DoctorEtching, 1883

Thomas Waterson Wood, His Own DoctorEtching, 1883Thomas Waterson Wood’s His Own Doctor shows “an exhorter in a Methodist church and a ‘professor’ of white-washing” self-medicating against a fever. Wood’s African-American scenes show him to have had a keen sympathy with his subjects. However, to me his portrait of an infirm elderly African-American overplays the comic element. The hint of caricature detracts from the sharp observation of details such as the quilt robe.

Peter Moran Harvest at San Juan, New Mexico(also known as Threshing Grain at San Juan Pueblo, New Mexico Territory)Etching, 1883

Peter Moran Harvest at San Juan, New Mexico(also known as Threshing Grain at San Juan Pueblo, New Mexico Territory)Etching, 1883Peter Moran’s Harvest at San Juan is to me an incredibly beautiful, important, and moving work. Peter Moran was one of the first artists to come to terms with the American Southwest, and in this etching he responds with grace and respect to the ancient cultures of the Pueblos. There is nothing here of the comedy to be found in Thomas Waterman Wood’s His Own Doctor. Nor is there any false romanticism. Sentimentality and guilt have no place in this etching, which focuses completely on the spiritual weight of the here and now. The centripetal force of this composition intrigues and delights me. Sylvester Rosa Kohler explains the scene thus: “The Indians use horses instead of oxen to thresh their wheat, and they are just driving them into the threshing circle indicated by the upright poles. The ground occupied by the horses is the cleaning floor, the raised ground which forms part of a circle in the foreground, is the earth banked up in levelling the floor, and the refuse of several years threshing.” Peter Moran seems to have instinctually understood that he was observing something with more meaning than a simple harvest, for he invests the scene with a thrilling sense of significance. The traditional method of threshing depicted seems to have been discontinued from 1920, replaced by the use of a threshing machine.

The setting for Harvest at San Juan is the New Mexican Pueblo now officially known by its Tewa name of Ohkay Owingeh (“place of the strong people”). This was the birthplace of the great 17th-century Pueblo spiritual and political leader Po’pay (or Popé), who briefly united the Pueblos against Spanish rule. I have, quite separately from my print collecting and dealing, a strong interest in Native American culture, and Peter Moran’s etching speaks eloquently to me—as eloquently as the Tewa “Song of the Sky Loom”, as translated by Herbert Joseph Spinden in his Songs of the Tewa:

Oh our Mother the Earth, oh our Father the Sky,

Your children are we, and with tired backs

We bring you the gifts that you love.

Then weave for us a garment of brightness;

May the warp be the white light of morning,

May the weft be the red light of evening,

May the fringes be the falling rain,

May the border be the standing rainbow.

Thus weave for us a garment of brightness

That we may walk fittingly where birds sing,

That we may walk fittingly where grass is green,

Oh our Mother the Earth, oh our Father the Sky!