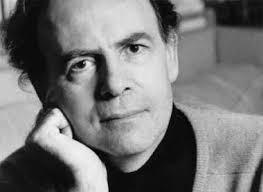

Yesterday I put two and two together and realised that the reason I’d seen a lot of brief but extremely unusual mentions of Patrick Modiano online was that he’d just won the Nobel Prize. Yes, I know, let’s put it down to age. But I love Patrick Modiano, he’s a wonderful author whose simply written novels, drawing on – and subverting – the genres of the spy novel, detective fiction and film noir are exquisitely complex and unnerving. I was trying to think how I could possibly describe the experience of reading one of his works and I could only come up with strange metaphors. They are like waking from a vivid dream, straining to catch those last fleeting remnants as they fade away. They are like being involved in a high-speed car chase only to turn the corner and find you are driving in solitary splendour. They are like the moment when Bugs Bunny runs off the edge of the cliff and doesn’t realize that he is pedalling pure air. He writes what I suppose I think of as proper literature – in which the story is perfectly formed, but the questions provoked by it are endless.

Yesterday I put two and two together and realised that the reason I’d seen a lot of brief but extremely unusual mentions of Patrick Modiano online was that he’d just won the Nobel Prize. Yes, I know, let’s put it down to age. But I love Patrick Modiano, he’s a wonderful author whose simply written novels, drawing on – and subverting – the genres of the spy novel, detective fiction and film noir are exquisitely complex and unnerving. I was trying to think how I could possibly describe the experience of reading one of his works and I could only come up with strange metaphors. They are like waking from a vivid dream, straining to catch those last fleeting remnants as they fade away. They are like being involved in a high-speed car chase only to turn the corner and find you are driving in solitary splendour. They are like the moment when Bugs Bunny runs off the edge of the cliff and doesn’t realize that he is pedalling pure air. He writes what I suppose I think of as proper literature – in which the story is perfectly formed, but the questions provoked by it are endless.

Take for instance the novel for which he won the Prix Goncourt,

Rue des boutiques obscures (

Missing Person). This was my first introduction to Modiano and I still recall it today. Guy Roland is a detective who decides, when his partner retires, to turn his skills onto himself. For fifteen years, since an accident left him an amnesiac, he has not known who he is. Armed with a fistful of clues he heads out on the quest for his real self, following a chain of witnesses, each of whom provides him with just enough information to carry on the search, but never enough for answers or closure. The trail of his old self runs out in the Second World War, when he seemed, like others around him, to be escaping the Nazis and the Occupation by fleeing to Switzerland. When Guy tracks down the last surviving person who might be able to help him, he learns that he has gone missing. And now I’m going to give away a massive spoiler, so you can hop to the next paragraph though the spoiler is intrinsic in understanding Modiano’s audacity as a writer… because the story ends with Guy in pursuit of this last witness, the original missing man chasing a missing man. The traces could not be any existentially lighter, and so it is almost as if Guy fades away into oblivion. It’s a shock ending, it was certainly not what I was expecting, and yet I didn’t mind at all; I may even have applauded. It was so original when I first read it, some 15 years ago.

The other novel of his I want to tell you about is

Voyage de noces (

Honeymoon). This concerns the documentary maker, Jean, who learns in a hotel in Milan of the recent suicide there of a woman he once knew. When he returns to Paris, he arranges his own disappearance and sets off on a quest to find out all he can about her. The search for information about Ingrid Teyrson and her husband, Rigaud, takes him back in time to the Occupation in France, when the couple were hiding out on the Côte d’Azur. Ingrid is Jewish and the couple are haunted by the figure of a man in a black raincoat who they feel sure is spying on them, in the hope of turning them in. How does this past match up with the present in which Ingrid has become suicidal? What happened?

So what have we got, then, in terms of preoccupations here? There’s an intriguing quest for identity at work in both novels, in which the hunt for the self is also the hunt for another person. But these quests which drive the narrative forward powerfully and compellingly are always doomed to failure – what’s missing can never be retrieved. There’s also a fascination with the Occupation as a kind of black hole – or maybe the sort of rabbit hole that appears in Alice in Wonderland – down which the experience of France as a nation disappeared, and now only fantastic traces remain that seem surreal and inexplicable. There’s nostalgia for a time when things were not strange and disconnected and wrong. But there’s also a pervasive sense of melancholia and shame. Modiano’s protagonists are not just postmodern, they’re post-lapsarian: guilty until proven guilty. We may not even be sure what they’ve done, but the strong sense of needing to atone, or to piece together a mystery that sheds them in a bad light, creates building blocks of the plot that feel like they’re made out of antimatter.

Of all the contemporary writers in France that I know of, Modiano is a surprise choice for the Nobel. His novels have a strong family resemblance – I imagine he might be accused of being a one-trick pony (though it’s a good trick). I cannot think he would go down well in America; if as a culture you want to outlaw the passive voice then Modiano’s enigmas of who-did-what and who-am-I-anyway aren’t going to please a lot of people. He’s very postmodern. And I wonder how much you have to understand French history to get the significance of the feeling aroused when it became clear that the myth of France as a nation of resistance fighters was built on shifting sand. But all that being said, I really like him; he’s an original, and his work of sophisticated simplicity is both eminently readable and full of menacing mystique.

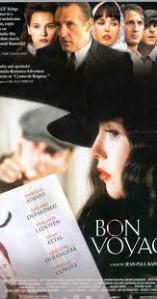

If you’re interested in trying Patrick Modiano in his simplest form, then I recommend the film: Bon Voyage. Modiano wrote the screenplay, about the converging lives of a disparate group of people who flee Paris when the Nazis invade. Watching the different storylines dovetail so neatly into one another, you can feel the hand of Modiano guiding the plot.

Yesterday I put two and two together and realised that the reason I’d seen a lot of brief but extremely unusual mentions of Patrick Modiano online was that he’d just won the Nobel Prize. Yes, I know, let’s put it down to age. But I love Patrick Modiano, he’s a wonderful author whose simply written novels, drawing on – and subverting – the genres of the spy novel, detective fiction and film noir are exquisitely complex and unnerving. I was trying to think how I could possibly describe the experience of reading one of his works and I could only come up with strange metaphors. They are like waking from a vivid dream, straining to catch those last fleeting remnants as they fade away. They are like being involved in a high-speed car chase only to turn the corner and find you are driving in solitary splendour. They are like the moment when Bugs Bunny runs off the edge of the cliff and doesn’t realize that he is pedalling pure air. He writes what I suppose I think of as proper literature – in which the story is perfectly formed, but the questions provoked by it are endless.

Yesterday I put two and two together and realised that the reason I’d seen a lot of brief but extremely unusual mentions of Patrick Modiano online was that he’d just won the Nobel Prize. Yes, I know, let’s put it down to age. But I love Patrick Modiano, he’s a wonderful author whose simply written novels, drawing on – and subverting – the genres of the spy novel, detective fiction and film noir are exquisitely complex and unnerving. I was trying to think how I could possibly describe the experience of reading one of his works and I could only come up with strange metaphors. They are like waking from a vivid dream, straining to catch those last fleeting remnants as they fade away. They are like being involved in a high-speed car chase only to turn the corner and find you are driving in solitary splendour. They are like the moment when Bugs Bunny runs off the edge of the cliff and doesn’t realize that he is pedalling pure air. He writes what I suppose I think of as proper literature – in which the story is perfectly formed, but the questions provoked by it are endless.