On Money by Martin Amis and Why I Think You’re An Alcoholic

I’m not really sure how to begin this review, or why I’m even writing it. My general impression of “Money” by Martin Amis, the entire time I was reading it, was that I disliked it. But I finished it anyway, and on occasion, even chose it over watching a television program. Which, if you know me at all, says a lot.

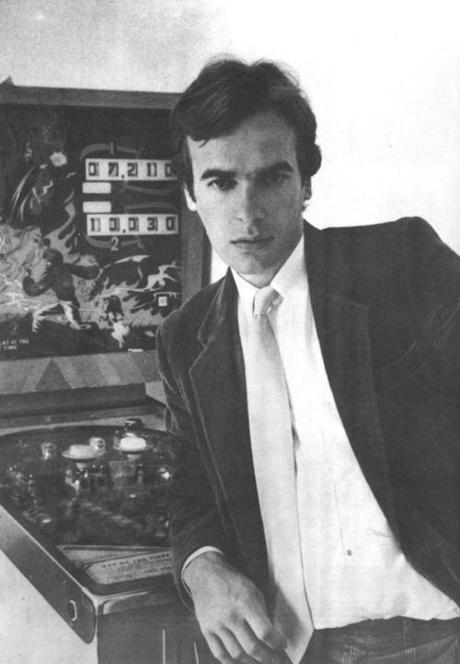

“Money” is about a British man named John Self who has made a pile of cash directing controversial television commercials in the late 70s and early 80s. Flush with material possessions and bored out of his mind, he decides to make a feature length film with a producer named Fielding Goodney, who is based out of New York. There is a lot of meta stuff that goes on as the narrative develops — for example, one of the characters whom John Self frequently encounters is named Martin Amis. Martin Amis a bookish author who keeps to himself and ends up re-writing the screenplay for John Self’s movie when the original, written by a lithe lesbian named Doris Arthur, turns out to be something of a joke. Martin Amis is also the name of the actual author of the book, and John Self is either the self hidden in him, or the self hidden inside of us. Or something stupid like that.

I have a feeling that Martin Amis was inspired to write the novel by three things:

1. Zeitgeist (the climate of money and excess that existed in the Western world in the early 1980s)

2. The bumbling alcoholic at his local bar who both repelled and fascinated him because he reminded him of the darkest parts of himself.

3. His Oedipal Complex

But then again, what white male novelist is not inspired by those three things?

The plot itself is ambitious — there are layers and layers of subtext that no doubt were lost on me, most of them having to do with the characters morphing into different people — and oftentimes tragically descriptive. But in retrospect, I appreciate the ambition, no matter how messy and contorted the execution, because it made for a lot of meat to read. And in the computer era, where meat is usually pared down by rounds and rounds of obsessive editing, it’s nice to read a book that’s over-written and rambling and takes forever to get through.

Now that I’m writing this shitty review, I realize that I did appreciate even the overly descriptive passages. While looking for one to malign, I only came across ones that, taken out of context, were kind of brilliant. For instance, when John Self gets wasted and takes a redeye plane back from New York to London, Amis writes:

“Boarding began, first class first. I stood up and entered the tube. And continued to travel deeper into the tubed night — to travel through the night as the night came the other way, making its violent sweep across the earth.”

Isolated, the language is brilliant; clumped all together, it’s fucking exhausting.

What most struck me, however, was the way that Amis captured addiction. Having been acquainted with quite a few alcoholics in my day — and recently, given up trying to save one of them — I appreciated how Amis doesn’t spare the reader from the idiotic repetition of a true addict. John Self drinks. He drinks some more. He constantly talks about drinking. Then he fucks something up and falls asleep and you have to keep on reading about his drinking, because the narrative is never disrupted by repose. You constantly want to slap him upside the head and scream, “Stop drinking you fucking idiot!” And then you read about his drinking some more.

One of the things that Caleb and I argue the most about is drinking. Caleb doesn’t understand what the problem is with other people drinking all of the time — he says that it’s their choice, so why judge them for it? But I grew up with the fear of alcoholism instilled in my heart by my mother, who gave me a shot of whiskey when I was 8-years-old and said to me, “Isn’t that disgusting? You know you’re an alcoholic, right?” It was her belief that given my genetic make-up, even at that young age, the diagnosis was unavoidable.

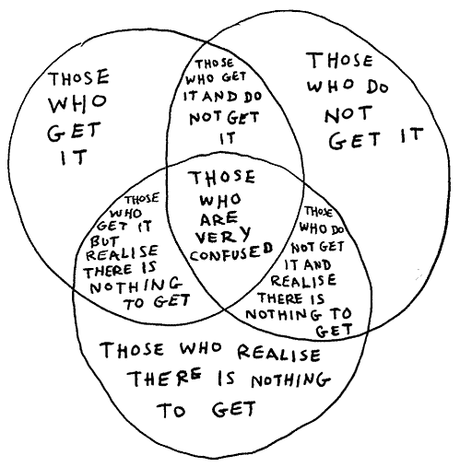

Her judgment made me judgmental. I judge people all of the time for drinking, and talk about it to the point of nausea. (Just in case you’re wondering, yes, I do think you’re an alcoholic.) It also made me really confused. I didn’t drink until I was 21. When I did start drinking, I was very cautious of it. Then, I spent a while drinking too much — but then again, I was single, and how can one possibly be expected to casually date without drinking too much? Now that drinking is not verboten or necessary, I’ve had some distance to consider my real feelings about alcohol. Am I really an alcoholic because I drink? Or is social drinking a natural, fun activity?

My inclination is that alcohol is poison, and if you’re drinking every day, you’re probably overdoing it. Ultimately, who fucking cares. But (to keep on obsessively talking about this) what I’ve realized, observing drinkers over the past few years, is that there is a big difference between a drinker and an alcoholic. Being a drinker is not great for your health, but ultimately is not terribly harmful. I am a drinker; I drink, but I get tired of it. I want to do other things. Being an alcoholic, on the other hand, is like being a prisoner. You are completely trapped in the repetition of what you must do every day, which is keep drinking. You stop being able to do other things, like watch movies or read or walk. All you can do — whether you want to or not — is drink.

Ultimately, being trapped doing any one thing is fucking boring. If you were trapped watching television for 16 hours a day, you would be bored. If you were trapped in a prison cell for 16 hours a day, you’d get bored. If you were trapped with me for 16 hours a day, you’d cut out my tongue. If you’re trapped on a bar stool all day, even if that bar stool changes locations or becomes a friend’s couch or a bench in the park, you would get fucking bored. And you also become fucking boring. And reading about it is pure boredom too. Which is why, as irritating as Martin Amis’ novel about a cash rich alcoholic was, it was brave of him to bombard the reader with the experience of it. Despite the tedium, I was able to finish the novel. And still, the sensation of it sticks with me.