Today's Emily's birthday (as in Dickinson), and I can't think of a better way to commemorate it than by sharing one of her previously unpublished "scraps" that Andrew Sullivan has been featuring at his Dish site recently. These are from Gorgeous Nothings, edited by Jen Bervin and Marta Werner (NY: New Directions, 2013). When I say that Emily's "scraps" haven't been published previously, I'm speaking of their publication in Gorgeous Nothings, from which the Dish blog has been drawing poems.

Here's a scrap that the Dish published yesterday:

But are notall Facts Dreamsas soon aswe putthem behindus—

I told you recently that I'd been spending time counting Samuels and chasing Nathaniels. What I meant by that statement: Steve and I spent some time prior to Thanksgiving at the LDS family history library in Salt Lake City, and one of my own projects during our time there was to try to disentangle a slew of tangled men named Samuel and Nathaniel Woodruff, all of whom had close connections to my Lindsey and Dinsmore ancestors in Spartanburg Co., South Carolina, and points west from there, where the connections continued for generations.

The tangle is daunting, because, like many families of that time and place, the Woodruffs persisted in recycling the same names over and over, so that in short time, one finds a multitude of Samuel and Nathaniel Woodruffs, all living side by side near what is today Woodruff, South Carolina, all connecting to Lindseys and Dinsmores. Both the federal census takers in 1790 and 1800 and county clerks appear to have recognized the problem of sorting Samuel from Samuel and Nathaniel from Nathaniel, since the census takers resorted to a Sr. and Jr. scheme in identifying some of these men, while the county records add to that scheme devices like II, III, and IV.

But it's not the Woodruffs I wanted to talk about (oh, you had assumed this was a posting about Emily Dickinson?). It's the Brooks. When I'd torn out plugs of hair sufficient to assure I'd be bald by Thanksgiving day as I tried to distinguish Sr. from Jr. from II, III, and IV, I then turned for relief to packets of loose court records in a county in Alabama in which my Lindsey and Dinsmore ancestors lived after they left South Carolina--and where they were closely related to a Virginia Brooks family they picked up along the way, as they sojourned some years in Kentucky before moving to Alabama.

I had known that the LDS folks were filming the loose court records of that Alabama county, since Steve and I stopped there on a trip several several years ago to do research at its archives, and folks from the Salt Lake library were there at the time filming the old case files. I hadn't known until this visit to the LDS library that they're now on microfilm and available to researchers.

I have a particular passion for those old court documents, because they tell us so much about how people in the past lived. Many of the case files are estate files stuffed with receipts for the medicine they bought as they died, for the care doctors provided, for the coffin in which they were buried and the funeral clothes in which they were laid out.

In touching the documents in the case files (via the magic of microfilm, at the LDS library), I feel I reach into the past and touch the people themselves--the people I'm researching. The bare facts of their lives have suddenly been transmuted into the stuff of dreams, and I'm able to dream a bit about who they were and how they lived their lives, in a way I can't do when I read a deed record, for instance, or a census entry.

As I scrolled through packet after packet of documents chronicling the activities of members of my family, here's something that leapt out at me: the court docket indexing these case files is chock full of entries for cases involving Brooks relatives of mine, in which one Brooks man after another was hauled before the court for assaulting someone, wreaking havoc on someone, committing mayhem. Case after case, all involving sons of a brother of my Brooks ancestor . . . .

By contrast, there's not a single case of this sort involving any of the sons of my Brooks ancestor, who was a Methodist minister. I wasn't surprised to discover the cases involving members of the other family, since I'd already found a newspaper account of the murder of one son of that family in 1846, which notes that he was a young man "of rather haughty spirit and domineering disposition," as well as of a "bullying nature," and that he tormented a young man who served under him in a militia company he commanded, who was "of humble and rather obscure origin."

And when the young man had had enough of being bullied, he slit the throat of his tormentor. Another newspaper account states that a brother of this Brooks man had such a "bellicose disposition" and a "spirit of belligerent activity" that he was involved in one "spat" after another, and lost an eye as a young man in one of his fights. An account of the (maternal) uncle of these Brooks brothers says that their uncle was "a man with a violent temper and was perhaps the handsomest man I've ever seen, but with a cruel mouth."

What accounts, I wonder, for the discrepancy between the lives of the sons of my Brooks ancestor, and the sons of his brother, all of whom lived in the same county? Did the fact that my ancestor was a Methodist minister mean that he raised sons less prone to violence than his nephews were? Does bad blood run in some families, as my grandmother would have been quick to conclude? Blood will out in the end, I can hear her saying . . . .

I notice something else as I leaf through these loose-paper court files: hardly any of the sons of the brother who produced bellicose progeny seem to have been literate. Almost all of them signed documents by making a mark. All the sons in my line of the family signed their names to documents.

Stories hide inside these scraps of antique paper, it seems to me, and those stories are, I suppose, what keeps me leafing through the scraps. How can two brothers raise such very different families? What effect does literacy have on violence rates? Does religious commitment sometimes curb tendencies to violence in some families (or does it sometimes do precisely the opposite)? Can the seeds of violence lurk in the blood of families that appear to have a propensity for such behavior?

Inquiring minds want to know. Just as they're fascinated by signatures of ancestors long dead, as if the signature itself carries a kind of thaumaturgic power to put us into direct contact with the person signing a document. As I read through the case files in which I found so much information about my Brooks family in the early 19th century, I also garnered a whole set of signatures of my Lindsey ancestors, which I hadn't previously had:

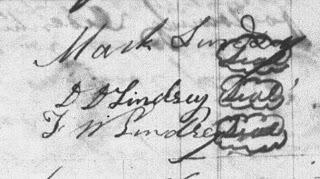

Like this one of my four-times great-grandfather Mark Lindsey (1773-1847) and his sons David Dinsmore Lindsey and Fielding Wesley Lindsey:

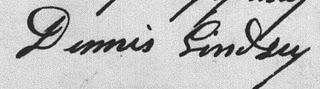

Or this one of Mark's son Dennis (1793-1836), my three-times great-grandfather, whose name passes down to me:

Or this one by Dennis's son Mark Jefferson Lindsey (1820-1878), my great-great-grandfather, who left Alabama for Louisiana in 1847:

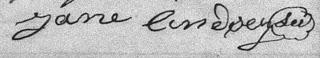

This signature of Jane Brooks Lindsey (1797-1852), Dennis's wife, on a receipt for her portion of her father's estate, reminds me that women were often not given the same level of education that men received in this time and place; Jane's signature appears to be the signature of a woman with less education than her husband had :

And what does any of this have to do with Emily Dickinson and her birthday, you ask? Well, there are those scraps of paper, without which we'd never have known Emily and her genius, and for which we owe a tremendous debt of gratitude to her sister Lavinia, who preserved them after Emily's death. Just as the scraps of paper from which I've garnered these signatures contain precious information about people in whom I'm interested because their blood runs through my veins . . . .

And there are those facts that can turn into dreams after we've put them aside--in the case of historical fact, with its dryasdust reductivity, fact that can suddenly and unexpectedly morph into dream, into narrative, if we permit it to move in that direction as we leaf through musty old papers and pore over forgotten documents in which history is enshrined . . . .

The daguerrotype of Emily Dickinson is the only authenticated portrait of her after her childhood, and is at Amherst College.