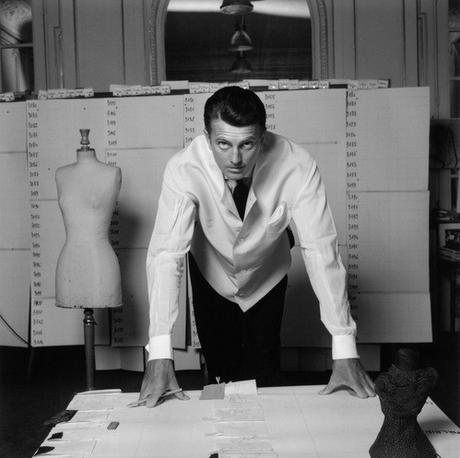

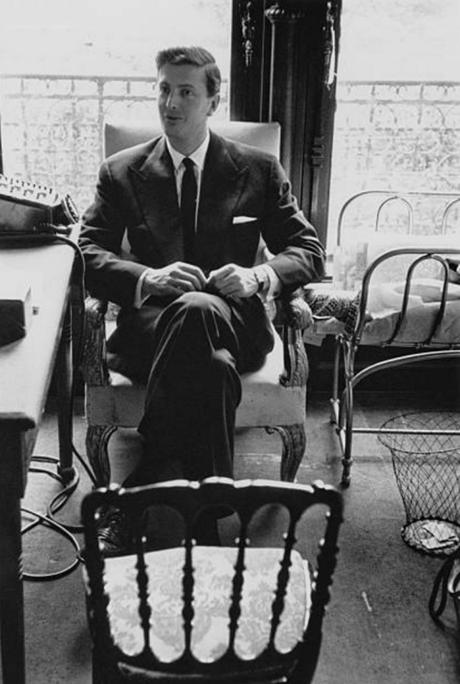

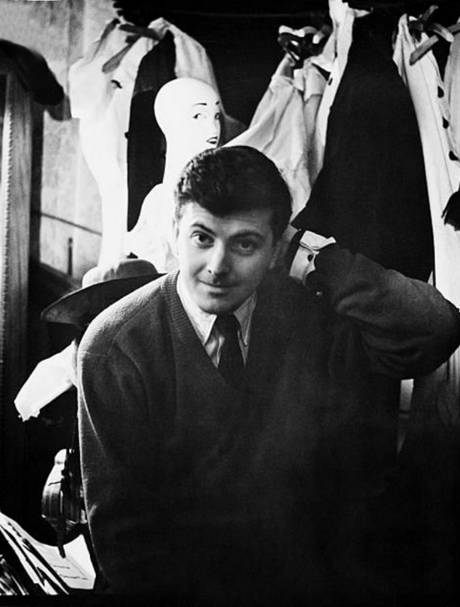

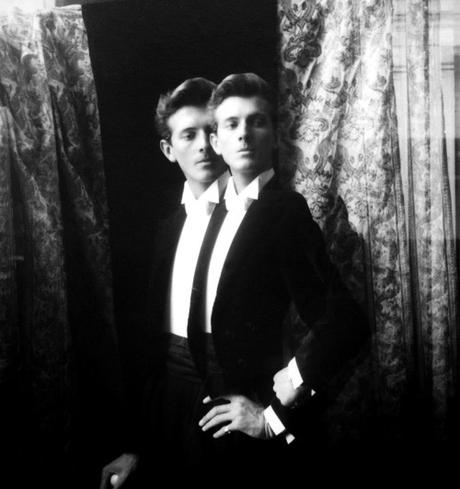

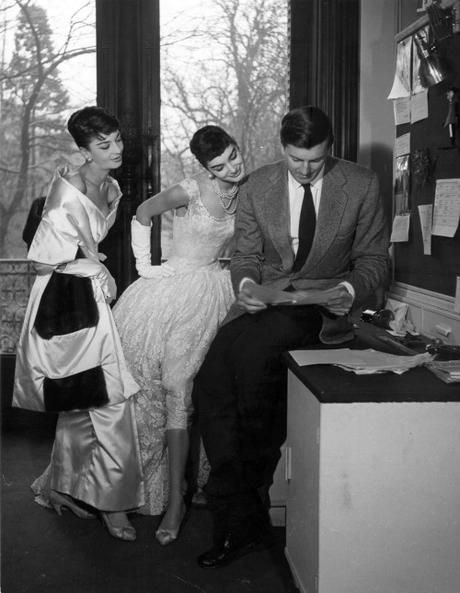

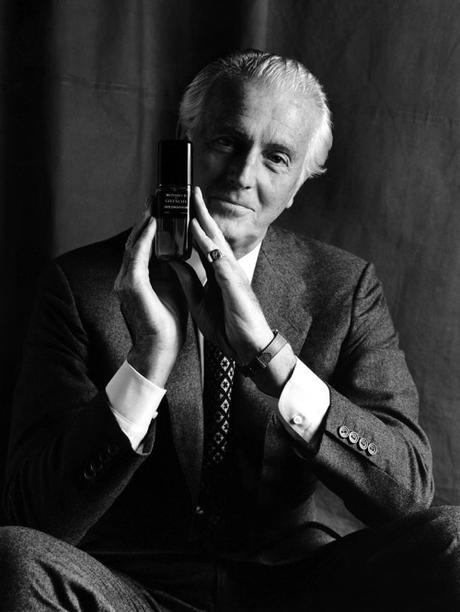

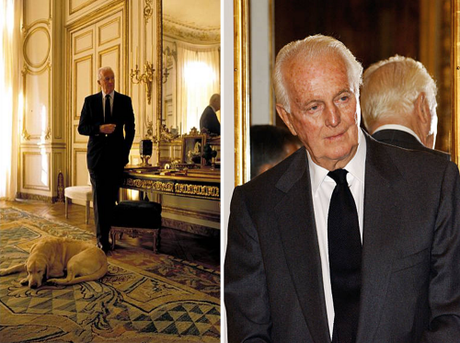

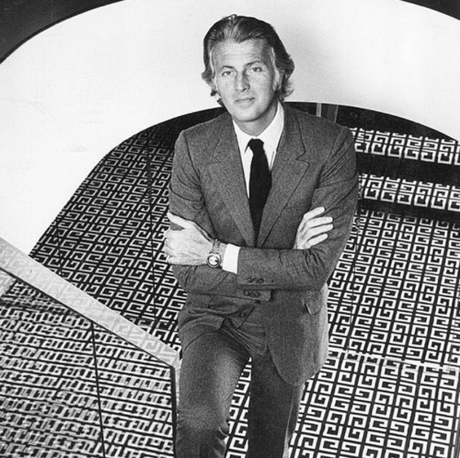

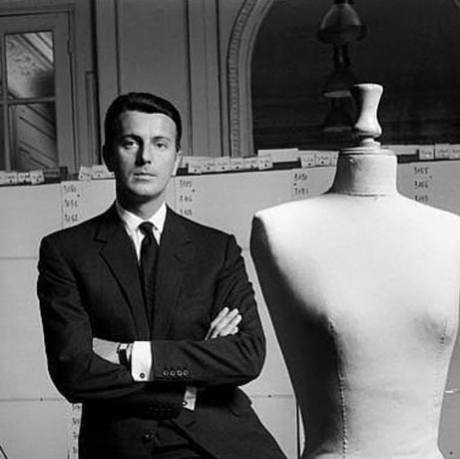

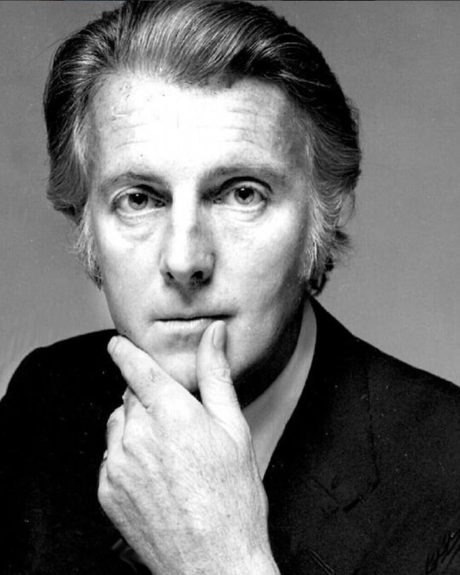

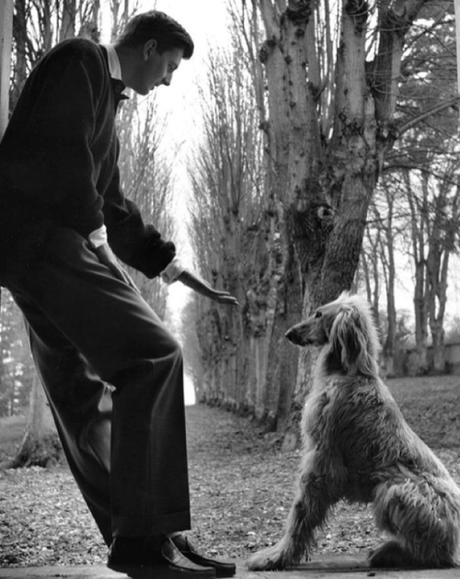

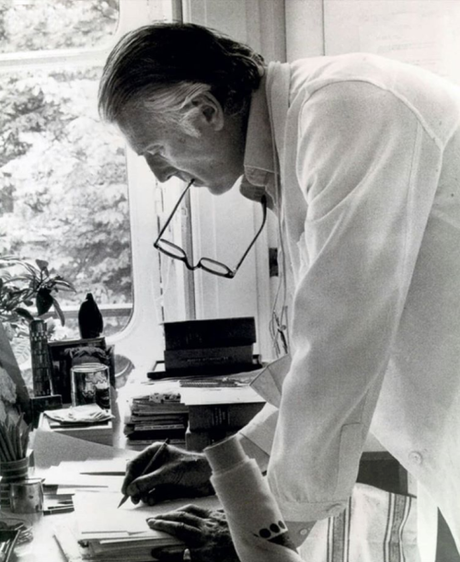

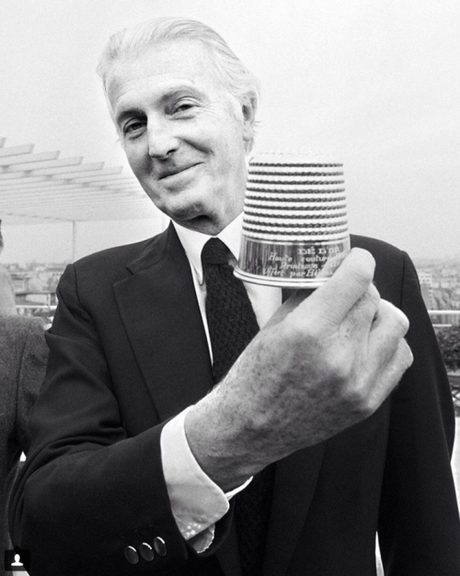

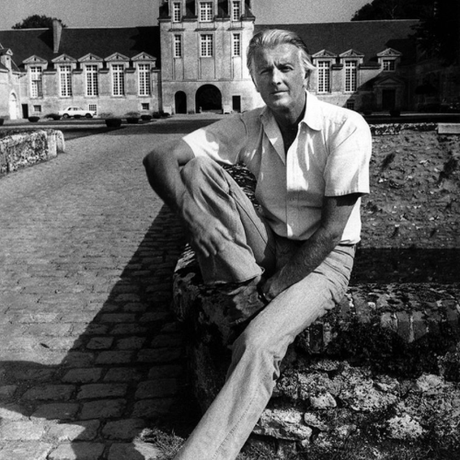

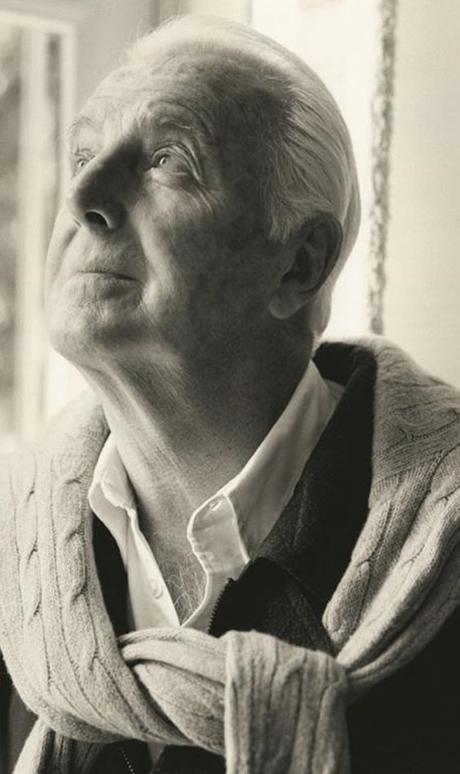

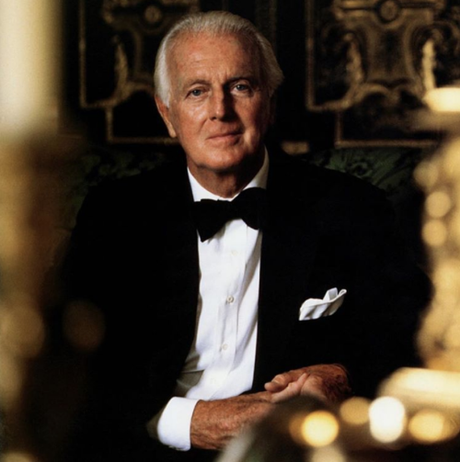

Hubert de Givenchy passed away a few days ago, and even if you’re not intimately familiar with his work, you’ve certainly seen it. Givenchy helped shape mid-century style, emphasizing the sophistication and grace personified by women such as Audrey Hepburn, Elizabeth Taylor, and Jacqueline Kennedy – all of whom he dressed. Hepburn once said Givenchy gave her a better sense of self-confidence and security (supposedly, she was uncomfortable with her looks, always feeling that her neck was too long, feet too large, and shoulders too broad). “My work [as an actress] went more easily in the knowledge that I looked absolutely right,” she said. “I felt the same at my private appearances. Givenchy’s outfits gave me ‘protection’ against strange situations and people. He is more than a designer, he is a creator of personality.”

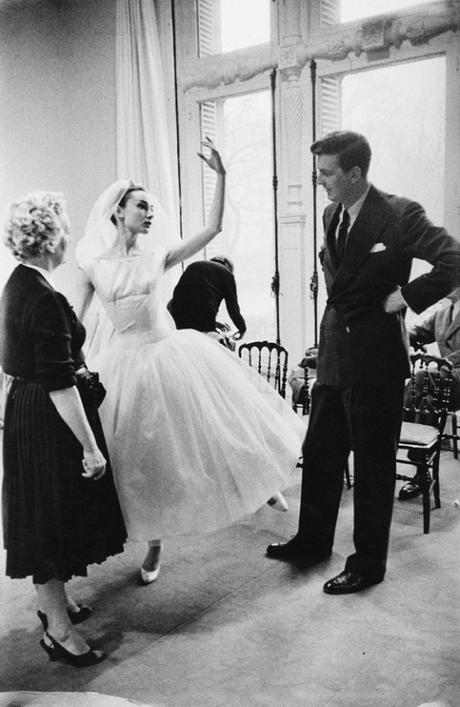

You’ve likely seen many of Givenchy’s more famous creations. The white floral gown Hepburn wore in Sabrina, the wedding dress with the dropped torso in Funny Face, and perhaps most widely recognized, the little black satin dress shown in the opening of Breakfast at Tiffany’s. Robin Givhan has a nice piece in The Wall Street Journal about the power of that sophisticated black dress, with the geometric cutouts and the “alluring way it framed the nape of the neck.”

The dress is not easy to wear. It follows the curves of the body. It reveals the arms. But it’s not a dress that constrains a woman. It requires effort but not sacrifice. The dress is special. It makes a woman want to slink about, controlled and teasing. It’s possible to envision it on all sorts of shapes — slim, like Hepburn, but also curvy. And it looks as perfect in 2018 as it did 50 years ago.

Givenchy didn’t invent the little black dress, but he gave it its enduring cachet. He infused it with meaning beyond the practical and versatile. The dress represented a lifestyle: glamorous, reckless, defiant, urbane. It was Holly Golightly’s dress. She was complicated and sad, confounding and charming. She was not Everywoman. She was exceptional, which is what every woman wants to be. And her signature dress was wondrous.

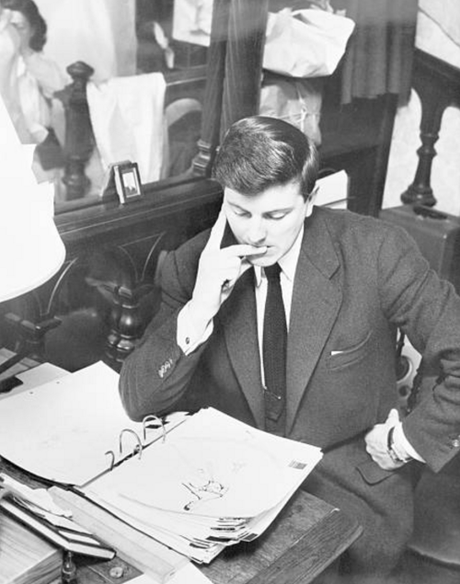

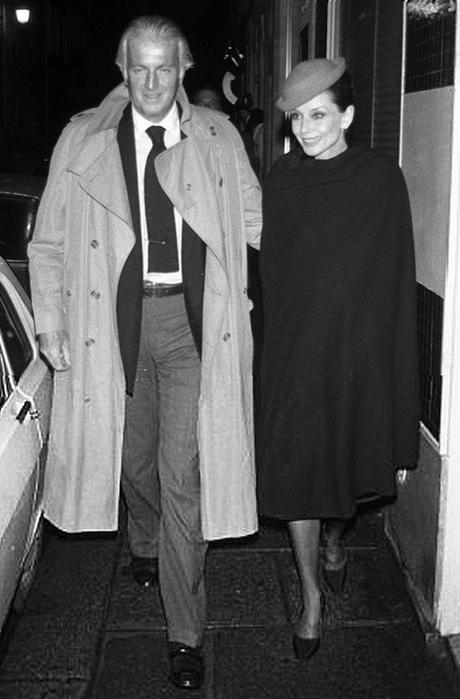

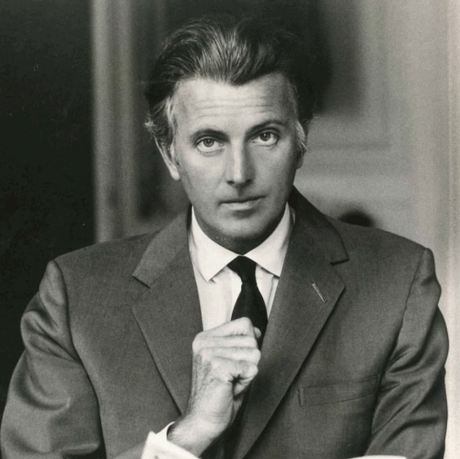

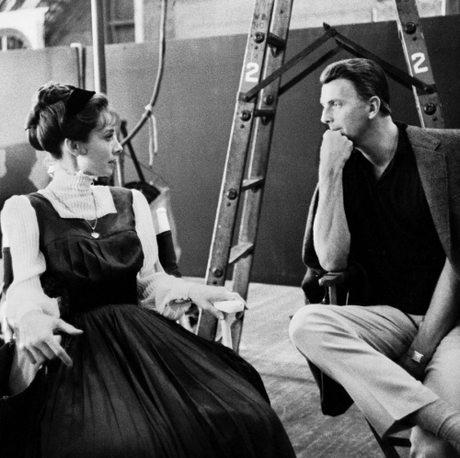

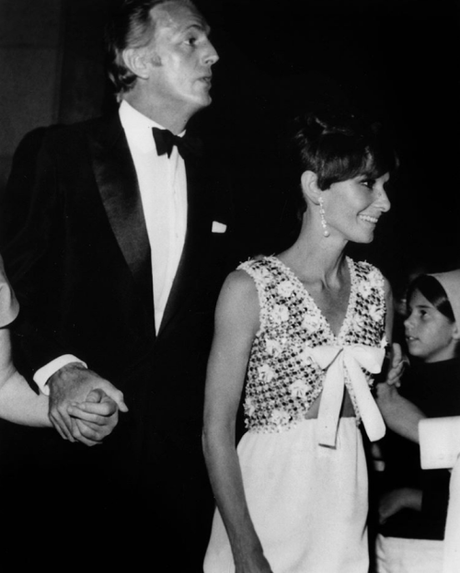

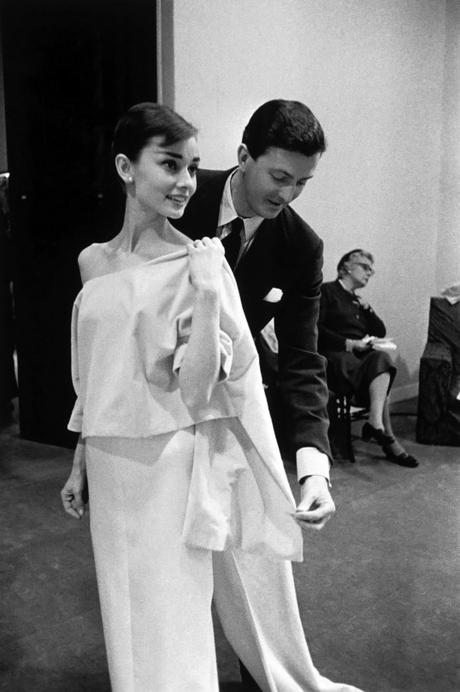

One of the notable things about Givenchy’s relationship with Hepburn – the original designer and his muse – was its sincerity. Hepburn served as an inspiration for Givenchy’s designs and gave the dresses life and color; Givenchy served as her clothier. Today’s designers still have muses, but the relationships are often bought and paid for, carefully calculated to generate press and sell clothes. In some ways, today’s fashion-and-Hollywood industrial complex was modeled after Givenchy and Hepburn, but it’s so thoroughly deformed that few would recognize it. Vanessa Friedman has a great article in The New York Times about this:

It’s worth reminding ourselves, in the age of what increasingly seems like celebrities-for-hire – when dresses worn by one designer to enter an award ceremony get changed to dresses worn by another designer for the after party and famous names profess undying devotion to a brand one season and then pop up in the ads of another brand the next – that once upon a time this was about two people who found in each other kindred spirits and worked together to craft two images: that of a woman and the man who dressed her.

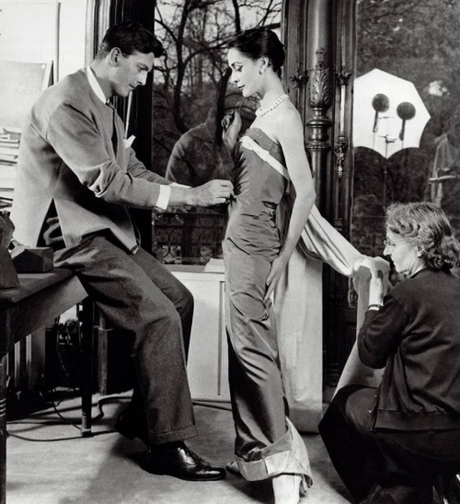

And that once “muse,” when applied to fashion and artist, was interpreted in the classical Greek sense of the word, as opposed to as inspiration for hire, or for public pitching. Mr. Givenchy and Ms. Hepburn found each other before either was really famous — the designer had only recently opened his maison; her first major movie had yet to be released — and they stuck with each other through seven films, from 1954 to 1987. He made not just the white dress she wore to win her Best Actress Oscar in 1954 (for “Roman Holiday”) but her wedding dress (for her second marriage, to Andrea Dotti).

And that is part of why the relationship worked so well: It was so mutually beneficial not just as a friendship, but as a professional signifier. When women bought Givenchy, they were also buying into a belief in long-term investment in elegance. That is why, as Hubert’s peers became known for their symbols — the pearls and camellias of Chanel; the New Look and Bar jacket of Dior — he was forever known for his muse.

Celebrities are still involved with fashion houses, but it’s on a pay-for-play basis. Their paid to wear the certain clothes in public; paid to appear in ads; paid to serve as brand ambassadors, influencers, and “faces.” And they’ll stay on as long as the milk flows. As Friedman notes, “perhaps it’s impossible to recreate what Mr. Givenchy and Ms. Hepburn had. The digital world moves too fast; people’s attention spans are too short; we know too much about celebrity behavior for it to have the same mystique and allure; no individual or brand wants to be so dependent on the other. Perhaps that’s history.”

I’ve been thinking about this issue of sincerity lately. Everyone says the ‘90s are back, but I think we’re actually seeing the revival of the early aughts. Today’s fashion enthusiast is a kind of new ironic hipster. People buy things to show they’re a higher-class of insider to other insiders, without necessarily giving away too much to the masses. Things are so bad, they’re good; things look like they’re from K-Mart, but are actually stratospherically expensive. Demna Gvasalia has made a name for himself off stupidly simple, easily recognizable pieces that allow people to signal their insider-ness – the DHL tee, the oversized stadium raincoat, the Champion sweats, the Polizei jacket, the Triple S sneakers. Supposedly half the line is made to parody the fashion industry, but the problem with irony is you never quite know when something is sincere.

Today’s most fashionable clothes aren’t bought because they look good or even cool – they’re bought to show status. To signal that you know so much about fashion, you know how to wear the right ugly things in the right ways. It’s the equivalent of throwing out as much trivia as possible about a band, or saying you knew about an artist before everyone else. And like with hipsters of the early aughts … it’s kind of annoying. It’s somehow painfully self-aware without being self-aware at all. Everything is pitched to show your placement vis-a-vis others in a subculture, rather than an appreciation for what’s good.

I was scrolling through some of the photos people have posted since Givenchy’s death, and feeling a bit bummed about what’s happened to some of these more legendary fashion houses. Hedi Slimane at Saint Laurent, Riccardo Tisci at Givenchy, and Denma at Balenciaga. They’ve been celebrated for bringing streetwear to high-fashion, but so many of the designs are too literal. Slimane’s literal interpretation of grunge; Gvasalia’s literal interpretation of Chinatown laundry bags; Tisci’s literal interpretation of what a meathead would wear to Las Vegas. Their work has been described as democratizing, but how democratic can it be to repackage streetwear in such literal forms and sell it for thousands of dollars? At the Saint Laurent thread on StyleForum, I’ve seen posters mock people for buying cheaper, more affordable versions of the brand’s aesthetic – which amazingly misses how the people who originally made the look cool actually shopped at thrift stores. This isn’t democratic; it’s stratifying.

I don’t want to get too wistful about it, but it feels like fashion once has a sense of sincerity that’s now missing on the part of designers, celebrities, and even consumers. Martin Margiela was inspired by underground street culture, but he took his role as a designer seriously – things were made with creativity and imagination. Demna has said in the past that he’s only interested in “making clothes, nothing more” but that seems like an excuse to sell Jansport embroidered backpacks for $900.

I don’t wish for Givenchy’s clothes to come back – fashion thankfully moves forward – but I admire the designer’s sincere desire to create something good, his muse’s sincerity to support what she loved, and consumers’ sincerity to buy something simply because they liked it. Hubert Givenchy mostly refrained from commenting on Tisci’s work at his namesake label, but in a 2007 interview with Women’s Wear Daily, he allowed: “I suffer. What is happening doesn’t make me happy. After all, one is proud of one’s name.”