On David Foster Wallace, and Maybe You Shouldn’t Read This Because I’m a Lunatic

I thought I’d write a little something about “Every Love Story Is A Ghost Story” by D.T. Max, if only because as a writer, I found a lot within the pages I could relate to. “A lot within the pages I could relate to?” What am I, in fucking middle school? In defense of the following shitty writing, I’ve written two other reviews already today, so my critical writing skills are a little depleted.

“Every Love Story Is A Ghost Story” is a biography of David Foster Wallace whom I, before I read the book, was pretty sure I hated. He seemed to be one of those literary cult figures whom everyone talked about being so brilliant, but no one had ever read. Like James Joyce. Or Derrida. Derrida is admittedly not a literary figure, but fuck you, whatever. Even yesterday, while getting my nails done with a friend, I asked her if she had ever read any fiction by DFW, and when she said yes, she had read “Infinite Jest,” and when I asked her if she had finished it, she admitted that she had only read half of it.

I one time tried to read a story by DFW in the New Yorker — it was an excerpt from “The Pale King” — and found, without even knowing that it was by DFW, that it was unreadable. And I will read almost any short story in the New Yorker, just because I’m usually on the subway, and if I don’t read anything, I’ll run out of things to do, and have to listen to Beyonce on my iPhone. Then, I realized that the story was by DFW, and that he was trying to write a novel about the bliss of boredom told through the eyes of a low-level office worker at the IRS. At the time, I thought that DFW was one of those academic rich kid types, the one who never had to work but really idealized the process of working because he could essentialize it in order to fit some sort of solipsistic idea. Which is kind of true. And I felt like some kind of wronged victim of my own circumstances, which were not so dissimilar to his, minus the fact that I couldn’t concentrate entirely on graduate school ostensibly because I had to work for money, but secretly because I felt like I wasn’t smart enough to be there. I thought I knew what hard work was, because I worked hard, and hated every second of it. In actuality, I was a privileged little bitch myself. The point of this is that after reading DFW’s biography, I have a lot more sympathy for him.

Do you mind if I let ideas float? I’m tired of catching them, and compressing them down into succinct little packages of words. Fuck clarity. I took an Ambien last night before I went to bed, because the night before I had a horrible nightmare that involved a man in a joker hat in an escalade stalking me and a transvestite I was having sex with in a world in which there were so street lamps, and I really didn’t want a repeat of that. Ambiens are no good for thinking the next day, however, and this one didn’t put me to sleep for a full 90 minutes. During which, by the way, I watched the season finale of Girls, which I thoroughly enjoyed. Hannah and Adam, those crazy nutjobs, indulge in their mental illnesses and end up back together? Sounds like my fucking family, I love it. Did that even happen though? I might have been hallucinating.

Anyway, back to DFW. In his early years, like most intelligent but alienated kids, he was sort of a dick. He was competitive, and a bigtime white liar, and very self-centered. He was also clearly brilliant — the top of his class at Amherst, and beloved by his professors. Through a lot of dissemblance and hard work, he was able to convince those around him that he was something extraordinary, because he himself wished with all of his heart that it was the truth. I find that when I wish for something, it actually materializes, usually because I focus all of my mental energy on achieving it — I haven’t even read “The Secret,” isn’t that AMAZING??!! That wasn’t the case with getting boobs, however, which I wish and hoped for without success, obviously.

Starting in college, DFW few nervous breakdowns, which landed him in a few mental institutions, and then finally in a half-way house. And that really humbled him. I don’t know, or maybe it didn’t, I don’t really feel like getting into it. I was sort of annoyed that D.T. Max brushed over David Foster Wallace’s mental illness — for instance, he merely mentions fits of anger when he was little, and subsequent signs of distress, all of which I easily recognize as early onset bipolar symptom — because I feel like he didn’t want it to be a central part of his subject’s narrative. But then I appreciated that Max focussed mainly on DFW’s writing. A biography can’t be everything you want it to be, if it’s done well — Max is a clear thinker, and in being clear, has to focus on one theme. The good news is that the gap leaves plenty of room for someone else to write a treatise on DFW through the modern day lens of what it means to have a brain that is sick. My brain is sick, a lot of the time. I only recently have come to see it as something I can’t fight, but rather have to succumb to, like I have cancer or a thyroid disease.

But back to me, again. I mean, back to DFW. This post is getting as confusing as the first 100 pages of “Infinite Jest,” from what I know of it!

DFW, it turns out, came to writing much like many of us writers, or really anyone who is passionate about anything that’s not an unhealthy relationship. While he was writing, he didn’t notice that time was passing. It was the one thing in the world that was a relief to him.

I’m not even going to attempt to find a quote to support that statement.

But, like most writers, he frequently had internal crisises. There were times that he thought he could never write again. There were times that he felt certain that he had lost his talent. There were times when it no longer contained any joy for him, and he thought about giving it up.

Here’s a quote to support that. “Wallace considered, he wrote Franzen, ‘forgetting about writing for a while if it’s not a source of joy. Who knows. Life sure is short though.’ He thought about focusing on his nonfiction.’”

What was most poignant for me, especially after the crisis I had getting my book rejected last week and having to face the fact that I might not be very good at writing fiction, was that DFW might have been somewhat similar to me. Although I’ve never read any of his essay collections — or, to my knowledge, his magazine articles — from what I can discern from people who are honest about their feelings for him, and from Max’s biography, is that DFW was an excellent, effortless nonfiction writer. But fiction did not come easily to him, and when it came, he had difficulty following his plots, and developing his characters. I am by no means equating myself to DFW here, but it was an interesting thing to realize, that as a writer, even a great writer, you might actually be better at writing about real life than you are at constructing it. The opposite is true of Zadie Smith, who weaves a great story but is an absolute terrible essayist. Who knew that it wasn’t a choice? Not me.

How you really know that DFW was brilliant was that in his later years, he became very humble. He truly tried to live a good, simple life. He realized that although his mind worked at a high wattage, it didn’t make him better than other people. He calmed the fuck down, and stopped trying to bring Wittgenstein into every conversation, and started reading Tom Clancy. Again, if you want me to prove that, sorry, you’re out of luck, but you can definitely borrow the book from me.

What’s second most interesting, after realizing that DFW, despite his cult status, was not a great fiction writer — at least not from what I gleaned from the biography — was how he became this sort of untouchable god of fiction. I’m always very confused about how mediocre, or even bad, things get lauded as great things. There are two obvious reasons for this:

1. People don’t understand them, but feel like they should because like the New York Review of Books wrote an equally unintelligible review, or their smart college roommate bragged about how awesome it was, so they’re afraid to admit they don’t get it.

2. The mainstream media, especially before the Internet, was composed of like 10 different publications, and sort of had an iron fist over culture. Most people are largely afraid to think for themselves, even though they’re entirely capable of it, so they rely on certified critics to lead the way. And those critics are not necessarily smarter, nor do they have better taste — they themselves follow the lead of publicists, or what they perceive to be the public consensus, because it takes a lot of bravery to be truly critical. You have to be willing to stomach it at a deep personal cost. Sort of basic human nature.

Those reasons seem too obvious though — I always suspect that I’m the one who’s missing something. Sort of like how I was convinced that our car got stolen for drug money this past weekend, when actually it turned out to be towed by the movie production company who is filming “The Americans” in our neighborhood. Turns out, dismayingly, that I was the idiot. In the same sort of vein, maybe some fiction (like that of DFW) is sort of supposed to be impossible to read except by a very select group of people, and I’m just disdainful because I’m not one of them.

Anyway, DFW sort of dreamed of being a lauded hero in his youth, and it came true. Movements — in his case, I think he kind of birthed the sort of writing we do today on the Internet, by which I mean it was loose and personal and full of asides — need their icons, and he was plucked sort of by chance. The pressure must have been tremendous, and perhaps that, more than any other reason, is why he found writing fiction so troubling.But he did output a lot of great stuff — case in point his nonfiction writing, as I said before, all based on hearsay because I haven’t read it — so the fact that his fiction was difficult and inaccessible sort of didn’t matter.

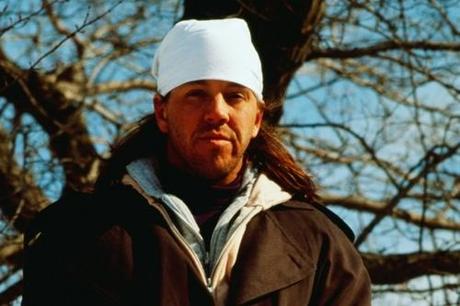

Also, it was a relief to find out that he was loveable not because he committed suicide or wore bandanas — but rather because he was honest and flawed and bared himself because he was weakened by his own mind. He would have been a fucking KILLER blogger.

Also, he seemed like he was an amazing, engaged teacher. I wish I could have taken a writing class from him.

All of this to say that you should read the biography, you shouldn’t take Ambien, you shouldn’t switch your medications if your mind is sick and one is working for you — lunatic lesson #1 — and also, DFW definitely is a cult icon, but despite that, I now genuinely admire him. The end.