Along with wine and pasta, olive oil is one of the food items Italy is most known for. Olive oil is the only oil extracted from an actual fruit, as opposed to grains or nuts, and is one of the most ancient manufactured foods.

Along with wine and pasta, olive oil is one of the food items Italy is most known for. Olive oil is the only oil extracted from an actual fruit, as opposed to grains or nuts, and is one of the most ancient manufactured foods.The production of olive oil started over 5000 years ago in the Mediterranean region, where the olive tree is native. Over time, the production technology has evolved, but the highest quality olive oil is still produced according to the same principles through a process called 'cold press'. The harvested mature olives, along with their pits, are crushed into a paste, which is then pressed (or nowadays centrifuged) to squeeze out the oil. The resulting product is fruity and aromatic, naturally low in free fatty acids (more on this later in this article) and has high nutritional value, thanks to high content of vitamin E and other antioxidants. Because of the limited yield of this method, cold press olive oil has a relatively high market cost. As a result, extra virgin oil is normally enjoyed raw as a condiment, more than for cooking, also because of its relatively low smoke point (the temperature at which an oil starts smoking and burning, see the table below).

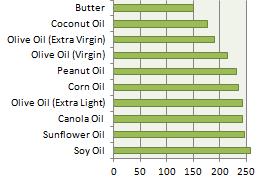

Smoke Points (°C)

When the oil resulting from cold press has high acidity levels or other organoleptic defects, it can be refined using a chemical process. Since the process also eliminates part of the phenols and the vitamins, the resulting product has a more neutral flavor and is considered of lower quality from a nutritional point of view. However, refined oil has a higher smoke point, which, combined with a less intense flavor and lower prices, makes refined olive oil the preferred choice for deep frying and sautéing.With the residues left after cold press, called pomace, more oil is extracted by the use of heat and solvents. This "second-squeezing" yields what is called pomace olive oil, which is generally not suitable for human consumption unless mixed with higher quality oils.

As per official European Union regulations, olive oil can have the following denominations:

Oils extracted using pure mechanical means:

- 'Olio Extra Vergine di Oliva' (Extra Virgin Olive Oil), if the percentage of free fatty acids is lower than 0.8%.

- 'Olio Vergine di Oliva' (Virgin Olive Oil), if the percentage of free fatty acids is lower than 2%.

Oils extracted with mechanical means and then chemically refined:

- 'Olio di Oliva' (Olive Oil), obtained with a combination of refined and virgin olive oils.

Oils extracted from pomace using heat and solvents:

- 'Olio di Sansa di Olive' (Pomace Olive Oil), obtained by mixing refined pomace oil and virgin olive oils.

Despite the substantial use of butter in northern Italian cuisine, olive oil is the Italian condiment of choice and it literally defines the cuisine of central and southern Italy. Along the coasts, olive trees are a constant part of the scenery and the production of olives and of olive oil is a central part of the economy (along with Spain, Italy is one of the largest producers, consumers and exporters of olive oil, as in the official report from the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development).

Unlike in North America, where olive oil is very much an elegant aliment used sparingly (olive oil tasting classes are even held), in Italy olive oil is an everyday choice and a very prominent ingredient. Combined with vinegar, it constitutes the most common Italian dressing. On salads, other vegetable oils are also used (e.g. corn oil, sunflower oil) - especially on the more delicate greens - but olive oil is overall the most popular. A drizzle of olive oil is often added on pizza (right before serving, also in its spicy version flavored with chilies) and on some soups (as a finishing touch and not stirred in). Raw olive oil is also one of the main components in many Mediterranean appetizers, including 'Caprese salad', 'bruschetta' and 'panzanella', and used in 'sottoli', oil-preserved vegetables and fish in jars.

Olive oil is also used in the preparation of countless Italian dishes. For instance, it is central in the very commonly used 'soffritto' (sautéed onion, celery and carrot), which a lot of dishes are based upon (e.g.: Bolognese sauce, most stews and several soups). In baking, olive oil is used in specialty breads and focacce. Olive oil is generally not used to make cakes or desserts, or used to fry anything sweet (where animal fat or other vegetable oils are preferred for their flavor).

Contrary to popular belief, olive oil is also widely used for deep-frying, especially the less pricy "refined" olive oil (which also features a lower smoke point). Certain preparations specifically rely on the contribution to the flavor that olive oil frying brings (for instance 'Melanzane alla Parmigiana' -eggplant parmigiana-). Other vegetable oils are also used for frying (e.g.: peanut oil, sunflower oil, corn oil). But certainly not Canola!

Canola oil is extracted from the seeds of a particular breed of rapeseed ('colza' in Italian, scientific name: Brassica napus) which was artificially created in Canada in the '70s. Natural rapeseed oil is considered inedible for humans because of its flavor and its content of euricic acid (which is mildly toxic). With Canola oil, instead, a much lower content of euricic acid was obtained, as well as better nutritional values and a more neutral flavor. The name 'Canola' (which stands for "Canadian oil, low acid") was chosen to commercially identify the new product and dissociate it from rapeseed oil. In the '90s, genetically engineered Canola capable to withstand certain types of herbicides was introduced. Not without controversies, this variety of Canola became the standard in North America.

Canola oil is exclusively produced in the United States and Canada, with only small amounts exported (mostly to Mexico and China). Canola oil is virtually absent from Europe where it only exists in its original form (rapeseed) and is used as animal feed and as a source for biodiesel. Despite the North American food organizations describe its properties as remarkable, Europeans are as suspicious of Canola as they are of any genetically modified products (as reflected in the article on the Italian Wikipedia).

Italians in North America strongly dislike Canola oil and find it particularly off-putting as frying oil because of its distinct flavor and smell. Given that refined olive oil is hard to find in North America, foodies have to resort to different oils for deep-frying, or accept that they have to use the more pricy extra virgin oil, and monitor its temperature to avoid reaching its (lower) smoke point.

Aside from their different properties, are some oils healthier than others? All vegetable oils are 100% fat, and provide 120 calories per tablespoon, but cooking oils can be quite different from one another. To appreciate these differences, we need to put on our lab coats. In nature, fats and oils are mostly made of one particular kind of lipids: triglycerides, a stable combination of 3 fatty acids and 1 molecule of glycerol. Small amounts of free, unbound, fatty acids are also naturally present (their percentage increases as the oil deteriorates). Since free fatty acids are unstable polarized molecules, they oxidize and cause the oil to go rancid.

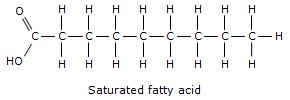

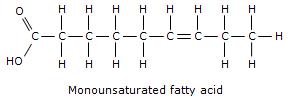

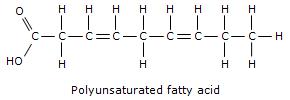

Lipids in general can be subdivided in two main categories based on their hydrogen content:

- Saturated fats accommodate the maximum possible number of hydrogen atoms. Saturation causes the fatty acids to be perfectly straight and this allows them to fit tightly one alongside the other. Because of this, saturated fats are usually solid at room temperature and are chemically quite stable - they naturally resist oxidation and have a relatively long shelf life. However, studies show that saturated fats are linked to high cholesterol and may cause heart diseases. Most saturated fats are of animal origin (e.g.: butter, cream, lard), but highly saturated molecules are also contained in tropical oils (e.g.: coconut oil).

- Unsaturated fats contain a certain number of double-bonds between carbon atoms, and consequently fewer hydrogen atoms. In unsaturated fats, the lack of symmetry causes the fatty acids to bend into more irregularly shaped molecules. As a result, unsaturated fats are generally liquid at room temperature and they are more subject to oxidation (to be preserved, they need to be kept away from light and heat). There is some evidence that unsaturated fats help lower blood cholesterol levels. Particularly, monounsaturated fatty acids (those where there is only one double-bound) seem to selectively lower only low-density lipoproteins levels, while keeping high-density lipoproteins levels intact (the so called "good cholesterol"). Monounsaturated fats are also preferred for frying as polyunsaturated oils tend to break down more easily at high temperatures. Canola, olive and peanut oil are all classified as monounsaturated fats. Corn, soybean, sunflower oils are instead mostly polyunsaturated.

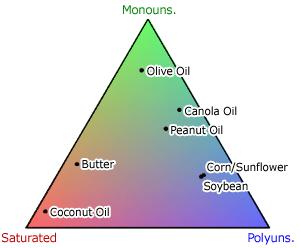

Finally, here is a diagram that shows the proportions of saturated, monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids in the most common cooking oils (data from "Harold McGee. On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen. 2nd edition (2004) - page 800").

Even tough Canola oil has the lowest percentage of saturated fats, some regard olive oil as the healthiest cooking oil because of its higher percentage of monounsaturated fats. However, the percentage of saturated fats is comparably low in both oils, leaving the ultimate choice to flavor and personal preference.