The classic movie Now, Voyager (1942), starring Bette Davis, is so familiar that I can pretty near play it in my head. Claude Rains as Dr Jaquith tapping his pipe against a valuable Chinese vase in the hall of a great Boston house. Bette Davis as Charlotte Vale walking nervously down the gangplank of the ship, the camera traveling up from her co-respondent shoes to the hat shading her face. Gladys Cooper as Mrs Vale lying crumpled at the bottom of the stairs. It is one of the great ‘woman’s films’ of the 1940s, much loved by my mother who spent her youth in dark cinemas, and by me, brought up to watch Hollywood classics on television.

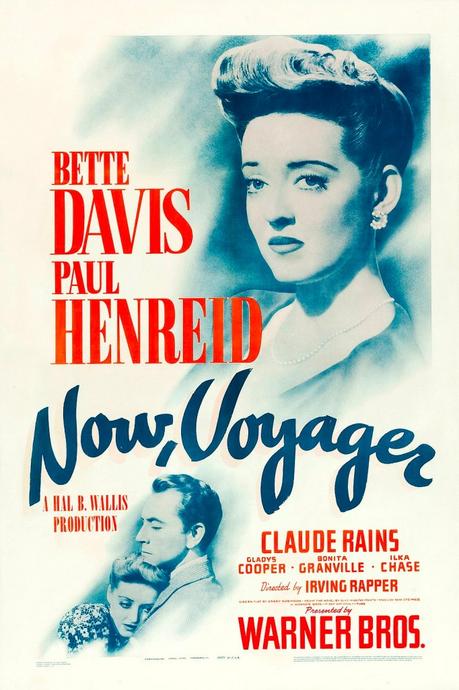

Film poster for Now, Voyager (,1942) (public domain)

Film poster for Now, Voyager (,1942) (public domain)

Before the film there was the book by Olive Higgins Prouty (1882-1974), a well-known American author in her day. Prouty wrote about women’s lives and family relationships, especially those between mothers and children, and so was easily dismissed. She was inclined to the melodramatic or fanciful on occasion, and pace could be a problem, but she was strong on sincerity and psychological insight. Prouty had a history of mental illness, especially after she lost two children at young ages, and as a result had first-hand experience of psychotherapy. So helpful did she find it that she incorporated it into her work at a time when this was unusual.

Olive Higgins Prouty (public domain)

Olive Higgins Prouty (public domain)

Now, Voyager comes from a sequence of five novels about the rich, socially superior and hidebound Vale family of Boston. Their common theme is personal fulfilment, as members of the family try to escape the restrictions and obligations society and family bring. One runs away to become a nurse; another has a discreet affair; and a third changes his identity.

Now, Voyager, the third of the series, is the story of Charlotte Vale, an unmarried woman of about 40, who is terrorised by her mother into a breakdown. She is sent to a sanatorium for treatment and then on a long sea voyage.

Sometimes tyranny is one of the expressions of the maternal instinct, Dr Jaquith told Charlotte.

Prouty, Now, Voyager, chapter XXIV

Charlotte to her mother: ‘I didn’t want to be born. You didn’t want me to be born. It’s been a calamity on both sides.’

Prouty, Now, Voyager, chapter XXIV

Charlotte’s mother, in response to Charlotte saying she wants to choose ‘where I sleep, what I read, what I wear’: ‘They told me before you were born that my recompense for a late child would be the comfort the child would be to me in my old age, especially if it was a girl. And on your first day home after a six months’ absence, you act like this! Comfort? No, Charlotte. Sorrow, grief.’

Prouty, Now, Voyager, chapter XVII

Dr Jaquith to Charlotte’s mother: ‘If you had deliberately and maliciously planned to destroy your daughter’s life, you couldn’t have done it more completely.’

From the screenplay of Now, Voyager, on which Prouty worked.

Prouty takes the title of the novel from a poem by Walt Whitman, and has Dr Jaquith send this to Charlotte as she sets out on her cruise:

The untold want, by life and land ne’er granted,

Walt Whitman, The Untold Want (1871)

Now, Voyager, sail thou forth, to seek and find.

Charlotte has no purpose – her ‘untold want…ne’er granted’ – and her opportunity to ‘seek and find’ comes through the ‘otherness’ of shipboard life. The passengers are a community brought together by chance, soon to be broken up. The ship is always moving, never settling, separate and between. It offers transition, freedom, possibility. With the help of her sister-in-law (her only ally), Charlotte has been transformed: a good haircut, a glamorous wardrobe (how the original readers, just out of the Great Depression, must have relished the descriptions of the clothes) and even a new name. The wardrobe belongs to the sister-in-law and the name to an acquaintance who at the last moment could not make the voyage, and the effect is to free Charlotte from herself.

Crossing the Atlantic, Charlotte hides in her cabin but at Gibraltar Renée Beauchamp emerges for an excursion ashore.

She looked as if she might have been recently ill. She had little natural colour, and no artificial color whatsoever. … She was dressed in the conservative good taste that is expensive. A navy-blue costume, very plain and very perfect, with a small snug navy-blue hat on her close-cropped head. … She caused much comment among the other passengers because of the incongruity between her distinguished appearance and her wary manner.

Prouty, Now, Voyager, chapter I

Bette Davis as the transformed Charlotte Vale, as she walks down the gangplank (screenshot from the film trailer, public domain)

Bette Davis as the transformed Charlotte Vale, as she walks down the gangplank (screenshot from the film trailer, public domain)

Charlotte of course meets a man, Jerry, and a shipboard romance is kindled. But she is very uncertain of herself, and he is unhappily married and working at a job he hates. Their story is told slowly, with much exploration of the couple’s feelings – the love they feel for each other, their enjoyment of each other’s company, their fear of the future, their anxiety about hurting Jerry’s family and damaging their own reputations – in the neutral, even safe, environment of the ship.

Prouty, who seems to like pairs and parallels, gives us in flashback the story of an earlier romance on a cruise. Charlotte, aged about 18 and full of optimism, falls in love with a junior officer. Her mother is traveling with her, finds out about them and ends the affair. The episode shows us the personalities of both Charlotte and her mother: the one’s warmth and sincerity and the other’s cruelty. As it happens, the mother is right to reject the young officer, but her brutality is breath-taking, and Charlotte is still hurting years later:

Again she felt the old anguish, or was it pity, for that defeated, demoted, deserted girl … cut off from her source of supply of courage and confidence, reduced finally to uncontrollable weeping, while her mother, with that patronizing gentleness which always accompanied one of her victories, brought her hot milk and bromides … .

Prouty, Now, Voyager, chapter VI

Gladys Cooper as Charlotte’s mother, Mrs Henry Windle Vale (screenshot from the film trailer, public domain)

Gladys Cooper as Charlotte’s mother, Mrs Henry Windle Vale (screenshot from the film trailer, public domain)

When their voyage comes to an end, Charlotte and Jerry go their separate ways. She returns to Boston, and life with her mother. It is, however, a very different life, symbolised by Charlotte’s daring to light an open fire in the Boston living room:

‘No, no, Charlotte! Mother won’t like it.’ … ‘It’s never been lit!’ ‘High time it was, then!’ said Charlotte, as the flames leaped up.

Prouty, Now, Voyager, chapter XVII

It would be unfair to say what happens next. If you want to know the ending, read the book or, at least, watch the movie. The point is that her time on the ocean liner has enabled Charlotte to leave behind her old life, to ‘seek and find’.

Charlotte (Bette Davis) and Jerry (Paul Henreid) meeting during the voyage (publicity still, public domain)

Charlotte (Bette Davis) and Jerry (Paul Henreid) meeting during the voyage (publicity still, public domain)

Postscript: Olive Higgins Prouty is remembered as a literary footnote today. She endowed a scholarship ‘for promising young writers’ at Smith, her own college. Sylvia Plath was one who benefitted. The two women got to know each other, and Prouty helped pay for Plath’s psychiatric treatment. Plath then, some might think unkindly, put Prouty in her novel, The Bell-Jar (1963), as the character Philomena Guinea, a rich but not very good writer.