On an island in the New York Harbor, a quick ferry ride from downtown Manhattan, you can spend a night in a tent while enjoying an unparalleled view of Lady Liberty. The experience is hosted by Collective Governors Island, one of the many glamping destinations popping up across America. Glamping, which is a portmanteau of glamour and camping, is about "roughing it," but with the modern amenities of a luxury hotel - a real bed, plush furnishings, stocked minibars, massage tables, and attending stewards. Such experiences have been around since the early 20th-century with African wildlife safaris, but today's glamping retreats offer something local and democratic.

The Yelp reviews for Collective Governors Island are nothing short of hilarious. The campground is described as a "soccer field" and "dirt-filled." One reviewer complained that there aren't enough planned activities aside from movie night and s'mores. Another says the island is too quiet. More than a few say that sleeping under the stars - no matter how romantic the idea - means you have to suffer under a blanket of heat and humidity. This is because, well, the Northern Hemisphere tilts towards the sun in the summertime, and sleeping in a tent means it'll be hot. My favorite is the reviewer who complained there are bugs and wished there was a kiddie pool. The most sensible person wrote: "Some of these reviews are a bit ridiculous. I mean, it's CAMPING after all."

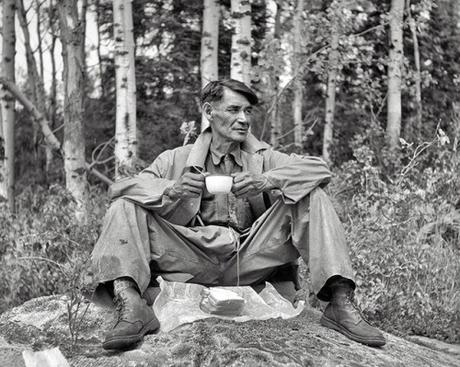

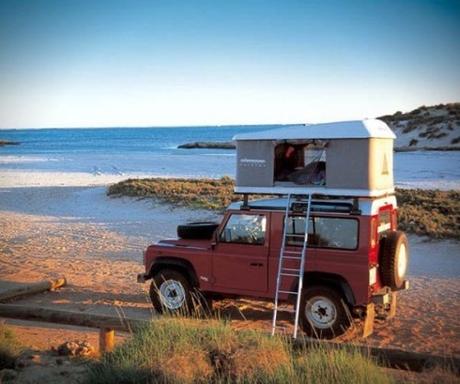

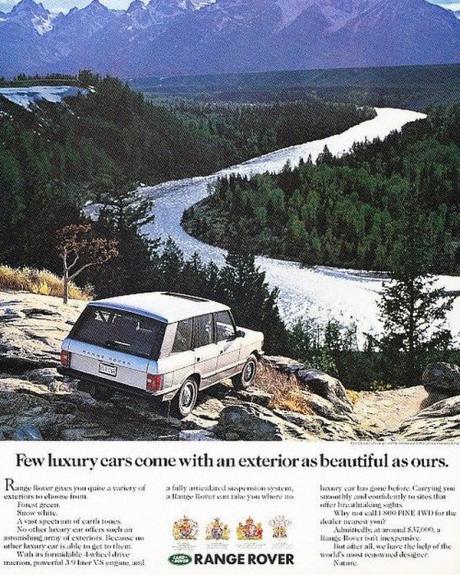

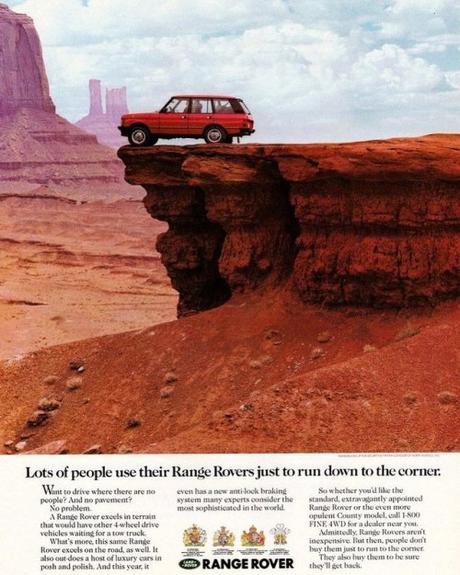

Then there are the critics on the other side of the aisle. Sportsmen, hikers, and outdoor purists often see glamping as a posh and phony version of the real thing. Why pretend you're reconnecting with nature when these RRL-like set-ups are often better than your actual home? Glamping is frequently described as inauthentic, but that raises the question: what is the most authentic version of camping?

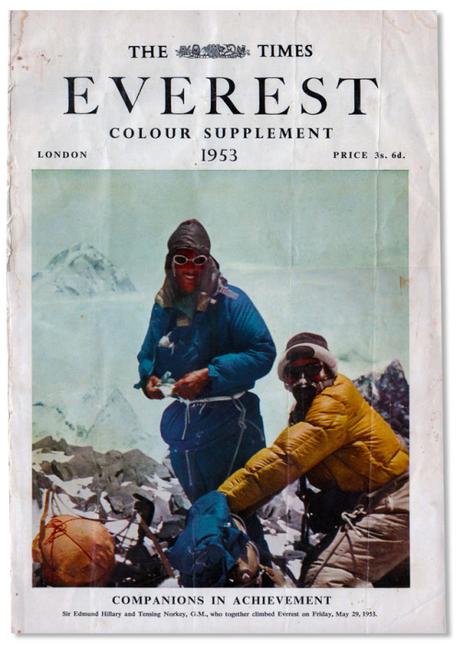

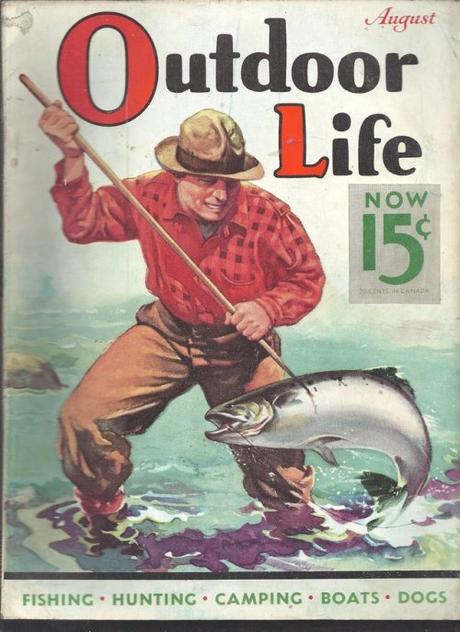

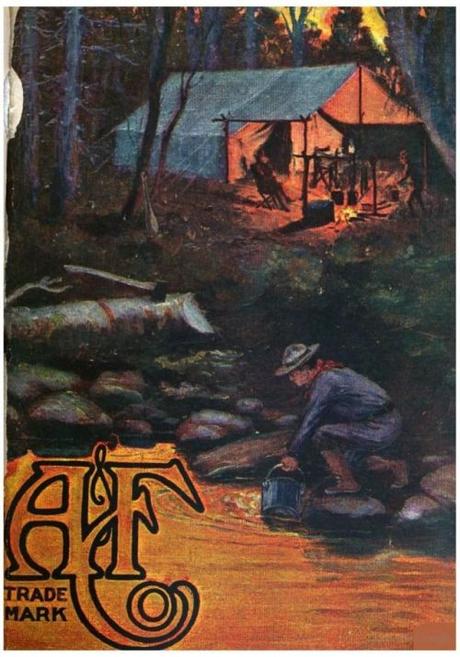

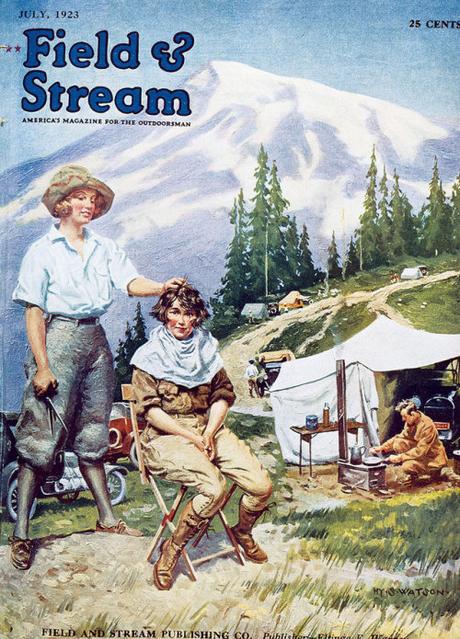

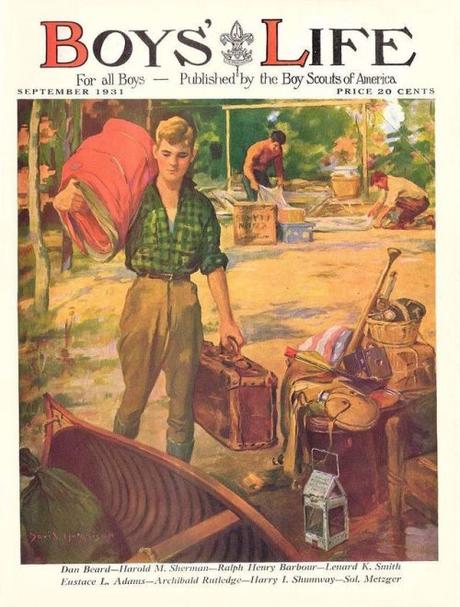

In popular imagination, camping has been around since the dawn of time, when cavemen gathered around a campfire and presumably shared stories through a series of grunts. But in fact, camping is a relatively modern invention. To be sure, soldiers have always camped as part of military campaigns (the term camping comes from the French camp or Latin campus, which roughly means "open space for military exercise"). Similarly, sportsmen, migrants, and pioneers have camped for centuries, but they only did so because it was necessary for some other activity - hunting, moving, or exploring. The idea that camping can be fun was first popularized in the 19th century when Victorians took to the River Thames for pleasure boating. And while modern camping came out of Britain, there's something special about the American version. Tap into the psyche of the American camper, and you can spin out a lot of fall/ winter style inspiration.

Why would anyone ever want to sleep outside? To understand camping, you have to go back to the people who first made the recreational activity popular. In the pre-railway days of 1853, a nine-year-old British boy named Thomas Hiram Holding set up camp with about 300 other fellows above some wooded slopes in Mississippi. They stayed there for about five weeks - the longest "fixed camp" Holding attended - but that was only the beginning of what would become a long, 1,200-mile journey across the American prairies, which lasted them from Spring till August.

"The plains were then uninhabited save for a few wandering tribes of Indians, probably a million antelopes, and possibly a half-a-million of wary buffalos," Holding later recounted as an adult. "Soon afterward, this gallant herd was swept away before the 'railway hunger,' i.e., they were shot by Buffalo Bill and others to feed the hungry natives who constructed the line. I fell under a wagon - weighing a ton-and-a-quarter - which passed over the small of my back but was not killed; many have been sorry, of course, since, but I could not help living on. In the following Spring, a wild and dangerous wagon trip and camp-back from Salt Lake City, up and through the Rockies, back to the States, closed the experience in that early stage."

A good many years passed before Holding would camp again, but the experience defined his life. As a young man, he spent time in Sunderland, England, lecturing on "Masculine Christianity," a philosophy that emphasized patriotic duty, discipline, self-sacrifice, masculinity, and athleticism as part of a person's broader spiritual development. Later, he became a traveling tailor and published texts on livery tailoring, coat cutting, and uniform making. His tailoring was advertised in the journal Tailor & Cutter (which later inspired the name of the online tailoring forum Cutter & Tailor). Holding's most famous published work, however, was a 1908 book called The Camper's Handbook, which he compiled after his many camping trips in Ireland and the United States. He was most reverent about a specific type of outdoor living: cycling camping, whereby cyclists rode across various terrains and set up camps for rest. In his book, the traveling tailor wrote:

It is now clear the poor clerk or workman, who wishes to see fresh countries at home and abroad, may gratify his whim and have a fine holiday on the weekly expenditure of his pocket money and be independent of weather, distance, or, to him, the prohibitive tariff of hotels. [...] The question comes in here, perhaps, as to which kind of holiday is more beneficial - a loafing or an active one? He who would spend a holiday in sheer laziness should take luxurious lodgings or quarter himself at a fine hotel, and next to the strain and exertion of eating, do literally nothing. To most men, however, young or middle-aged, who lead active lives and who are gifted with average energy, something less dormant is, surely, an advantage. The camp gives this - exercise without fatigue; fresh air night and day, and sufficient excitement to create interest, and remind a man that he lives.

The Camper's Handbook helped popularize the idea that you can sleep outside for fun, and that it might not only be better for your health but also spirit. Along with congregational minister William Henry Harrison Murray - also known as Adirondack Murray for his book Adventures in the Wilderness - these two men drew a straight line from the rustic nobility of woodsmen to the idea that urban commoners could enhance their life by becoming intimate with the wilderness.

First, some background. When it first emerged, recreational camping wasn't just about fun vacations with friends. It was an anti-modernist movement. Frederick Engels' seminal book The Condition of the Working Class in England, published in 1844, right around the time when camping became popular, gives a walking tour of England's polluted slums and soot-covered factory towns. "A town, such as London, where a man may wander for hours together without reaching the beginning of the end, without meeting the slightest hint which could lead to the inference that there is open country within reach, is a strange thing," he noted in the opening of his chapter on English towns. Regarding London, he continues:

The streets are generally unpaved, rough, dirty, filled with vegetable and animal refuse, without sewers or gutters, but supplied with foul, stagnant pools instead. Moreover, ventilation is impeded by the bad, confused method of building of the whole quarter, and since many human beings here live crowded into a small space, the atmosphere that prevails in these working-men's quarters may readily be imagined. [...] A vegetable market is held in the street, baskets with vegetables and fruits, naturally all bad and hardly fit to use, obstruct the sidewalk still further, and from these, as well as from the fish-dealers' stalls, arises a horrible smell. [...] Here live the poorest of the poor, the worst paid workers with thieves and the victims of prostitution indiscriminately huddled together, the majority Irish, or of Irish extraction, and those who have not yet sunk in the whirlpool of moral ruin which surrounds them, sinking daily deeper, losing daily more and more of their power to resist the demoralising influence of want, filth, and evil surroundings.

Like other significant social movements at the time - communism and the Arts & Crafts movement, the second of which promised to rescue workers from what Marx described as the alienation of labor - camping was about getting away from the dehumanizing effects of early industrialization. But the outdoor pastime took a particularly strong hold in America for several reasons. Like in England, the northern half of the US was going through an industrial boom after the Civil War. Cities were swelling in population; people were rubbing shoulder-to-shoulder with strangers. There was a lot of smoke, noise, and pollution. These conditions felt alien to the many Americans who grew up on small farms but had to migrate to industrial centers for work. Americans couldn't leave the city because they had jobs, but they also wanted to get away when they could.

In his book Heading Out: A History of American Camping, geography professor Terence Young says camping became popular in the United States for another reason: it connects us to the American mythology about the frontier. "The frontier promoted the formation of a composite nationality for the American people," Frederick Turner asserted in his "frontier thesis" at the turn of the 20th century. "This perennial rebirth, this fluidity of American life, this expansion westward ... furnish[es] the forces dominating American character." The frontier thesis states that the formation of the American identity and its ideals - liberty, equality, and lack of interest in high-culture being chief among them - came about by Americans pushing westward. In the frontier, there's no need for old, dysfunctional customs, established churches, or noble aristocrats. Everyone is equal in the Hobbesian sense, as even the weakest person can kill you in the state of nature. Out of this comes the social contract and universal protection.

But as the actual frontier closed around the turn of the 20th century, Americans headed back into the woods to rekindle those democratic, egalitarian ideals. Ralph Waldo Emerson, a naturalist, transcendentalist, and the father of American literature, felt people were too hemmed up by traditions. We're limited by social forms, customs, and habits, which prevents us from being our natural selves. But what are we without history, tradition, and customs? To find out, Emerson encouraged us to go back to nature. Henry David Thoreau's two years at Walden Pond, where he lived in a 3 x 4.5-meter cabin built on Emerson's property, allowed the writer to develop his philosophy on self-reliance - an American virtue if there ever was one. There's no stronger testament to Thoreau's legacy than his effects on the civil disobedience movements that followed. In 1846, he withheld paying poll taxes to avoid supporting the Mexican-American War and slavery. His masterwork Civil Disobedience, which promoted the idea that you should peacefully resist unjust governments, would later influence Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr, and the anti-Nazi resistance movement.

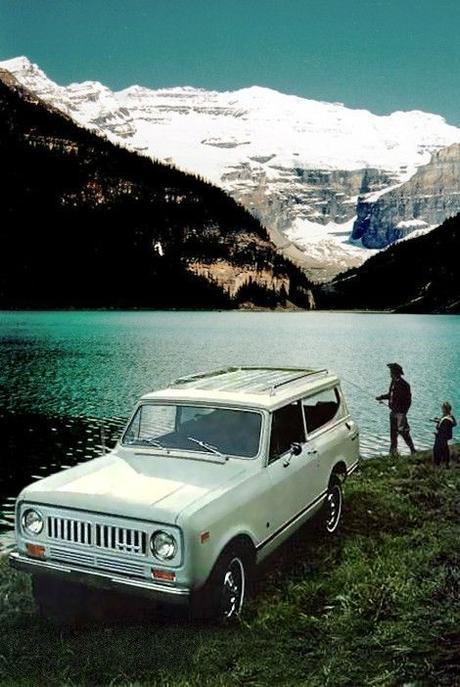

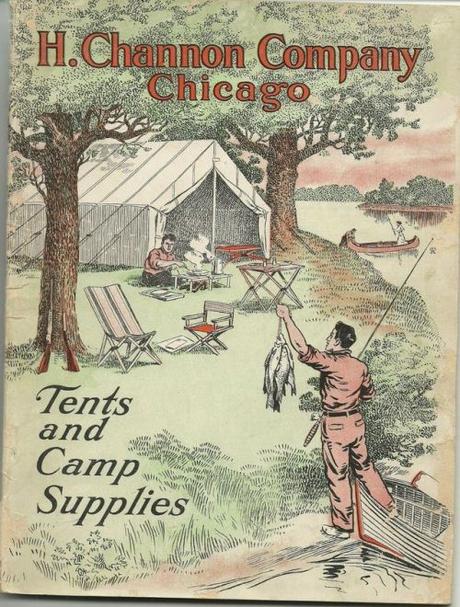

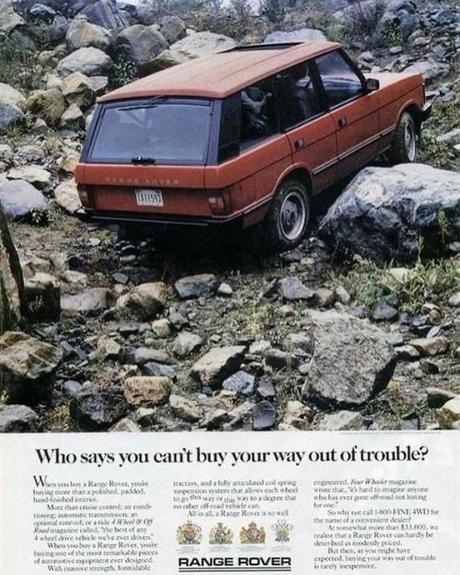

But as Young notes in his book, capitalism and regulation eventually emerged even in the wilderness. Early campers tended to be those of the upper classes - those who owned businesses and could afford to take vacations (the petite bourgeoisie, as Marx disparagingly called them). A market for specialized camping equipment soon bubbled up to serve those affluent people. Later, when the primary mode of American transportation switched from horse-drawn carriages to gasoline-powered automobiles, more people could afford to take trips out to the countryside. This democratization sped up the market process. Even more products appeared to serve the teeming masses that swarmed out into the woods.

Two things sprang out of this democratization process. First, people started arguing over which was the most authentic form of camping: cycling camping, car camping, canoe camping, backpacking, hiking, or trailer camping (cyclists and backpackers generally looked upon car campers as undeserving invaders). Second, as more people went out into the woods, there needed to be environmental regulations. Initially, campers could set up their tents anywhere, but they tended to congregate around the more scenic areas, such as near riverbanks. But in doing so, they were also killing the vegetation.

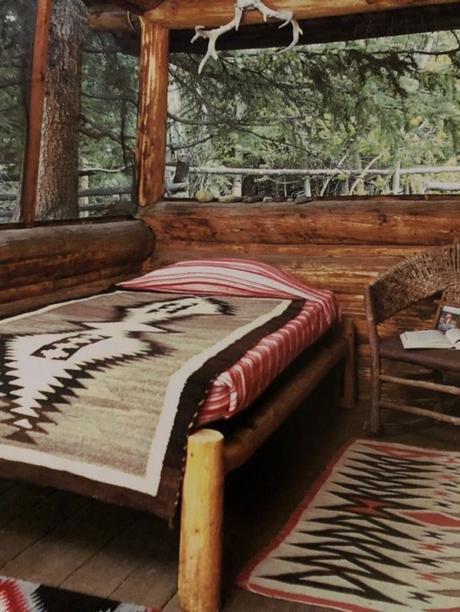

So, in the 1930s, the US forest service approached a gentleman named EP Minecky. The plant pathologist set up what would become the modern campground. Today every campsite now mimicks domestic life: there are wooden tables, water fountains and restrooms, designated roads, preset grills, and the heavy stones that allow you to safely set a campfire (the most ritualistic act of what should be a wild pastime). Even in the woods, and even in what was originally an anti-modernist movement, modernism emerged. In doing so, more people can enjoy the great outdoors while respecting the environment, as well as engage in activities that give them fulfillment and meaning.

Camping doesn't hold as much prestige as it did at the turn of the 20th century, but cities today are also much cleaner and more comfortable. Even Manhattan has as many as 60,000 trees lining the streets, and wild nature often intermingles with human-made art. Consequently, people don't feel as much of a need to escape. At a bar over the weekend, I was talking to some friends about possibly organizing another camping trip before the weather gets too cold. Most of us like camping just because it allows us to disconnect from the digital world, not flee from the Marxist hellscape Engels once described. Still, getting out into the woods is a wonderful way to recharge yourself. There's a stillness out there that lets you breathe. We may lead more comfortable lives today than those 150 years ago, but the virtues of feeling soft soil under your feet remain.

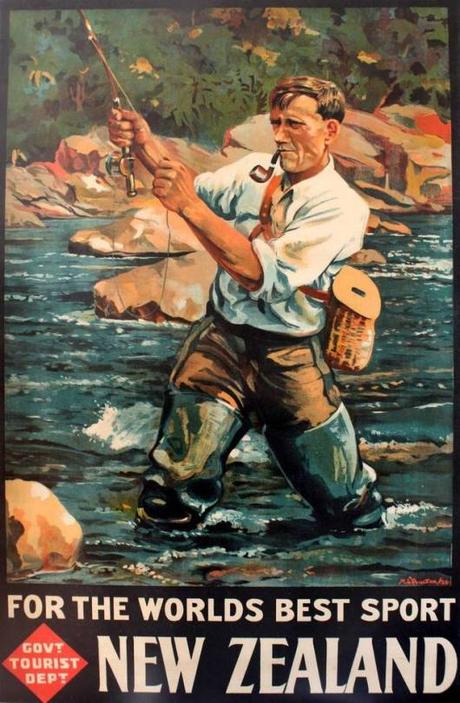

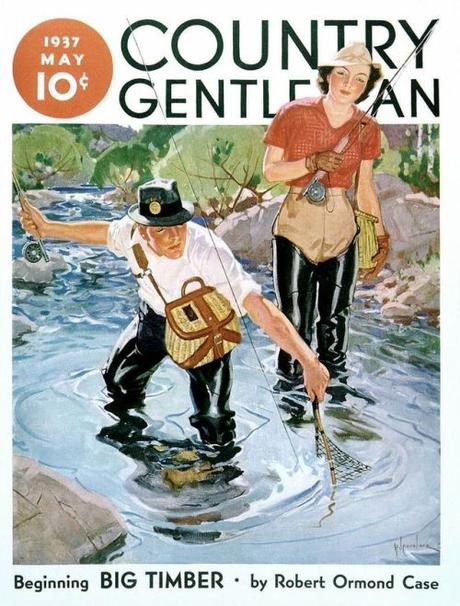

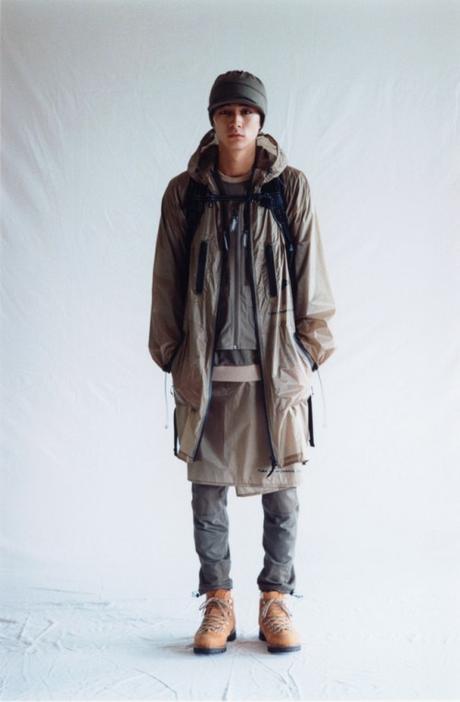

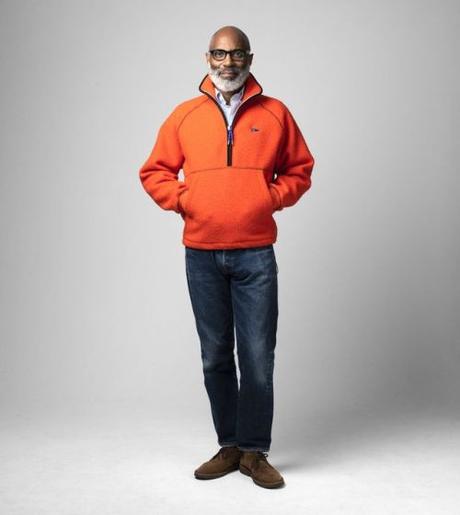

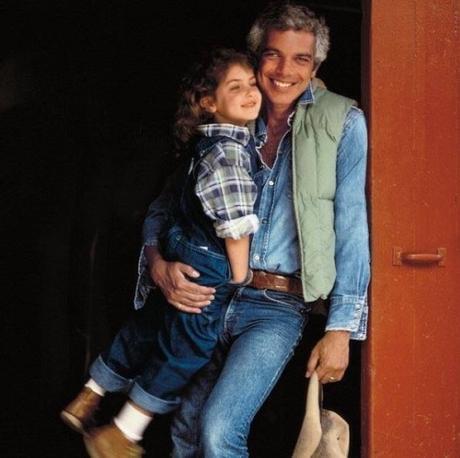

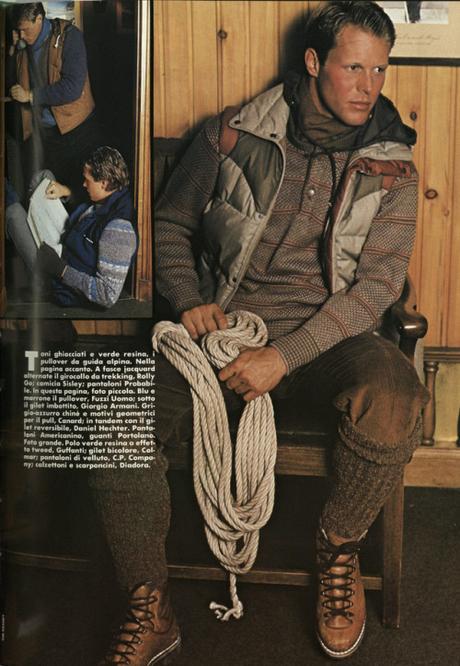

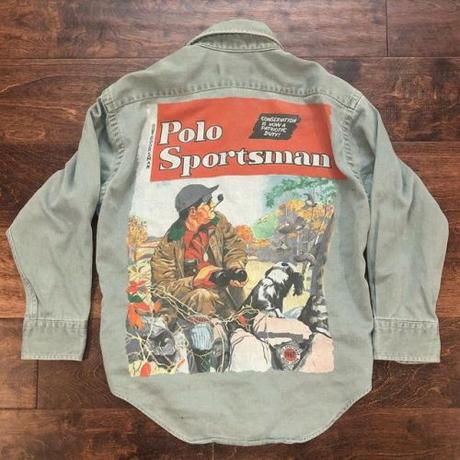

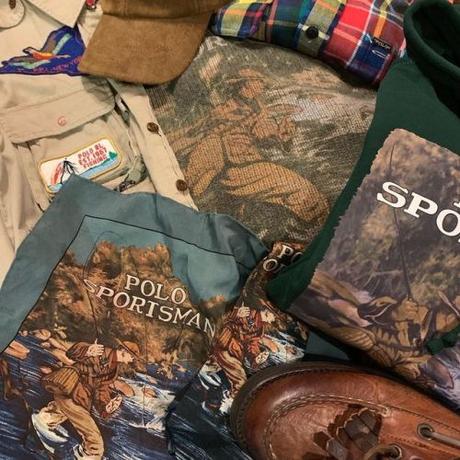

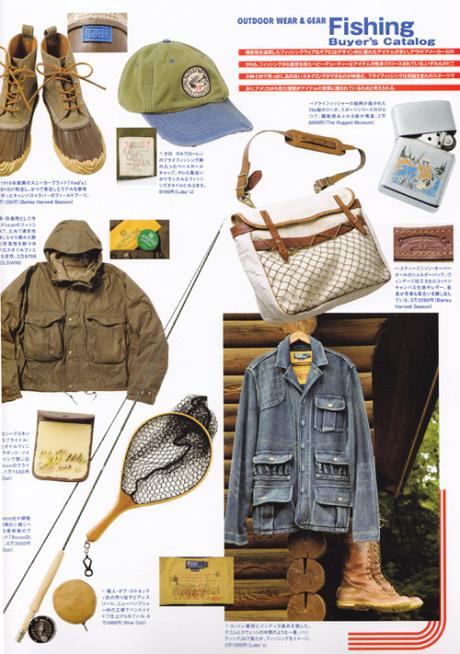

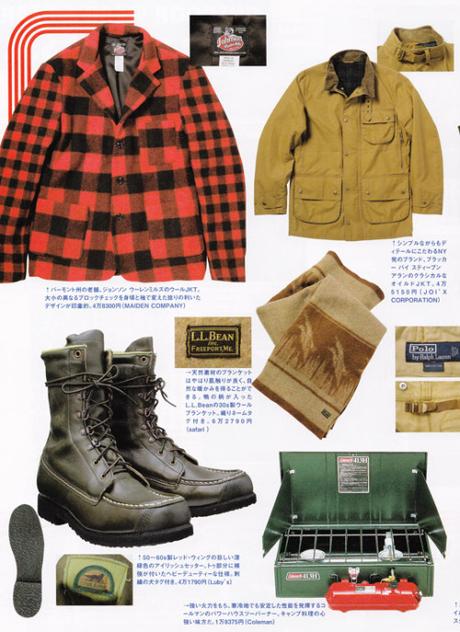

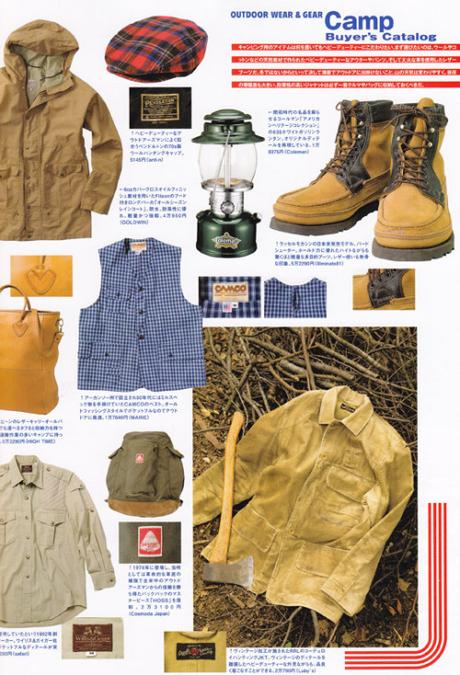

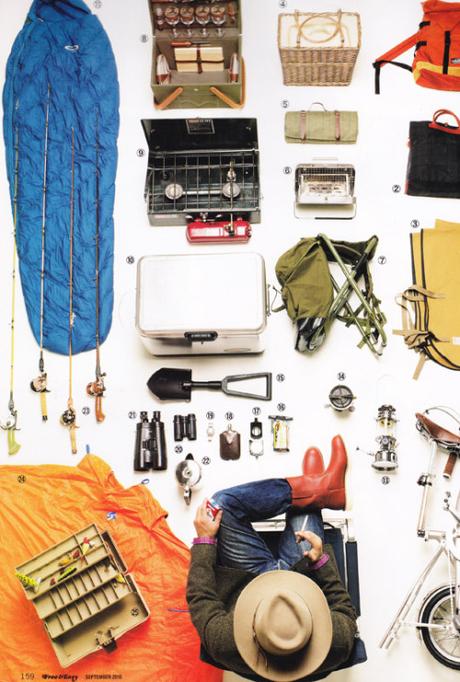

The outdoors is also an endless fount for fall/ winter inspiration. You may not be fishing for anything more than a good deal on Fifth Avenue, but tromping around in a fishing vest can restore that glorious feeling of what it's like to be a child out in the woods. Camp style is about remembering the good old days of outdoor campouts, sleeping in tents, and skipping alongside clear water brooks to catch diminutive insects. It's the sound of a running stream; the smell of a thick pine forest. The dream of one day working in the natural sciences. I particularly love Tony Sylvester's outfit above: a mountain parka layered over a thick turtleneck, paired with corded pants and a pair of Tyrolean walking shoes. Even in downtown San Francisco, you can feel a bit of the wilderness on your back if you have the right outfit. If you're looking for some camp-inspired gear this season, here are some options:

Outerwear: Start with your outermost layer. A waxed cotton Barbour jacket will always look good in this context, but if your climate allows, I also like the slightly more directional look of puffer jackets. Nigel Cabourn and Visvim's down coats look tremendous, but so does the cost of entry. Instead, you can try Rocky Mountain Featherbed, Crescent Down Works, RRL, Timothy Everest, Drake's, Eastlogue, and Aime Leon Dore's new collaboration with Woolrich. Kaptain Sunshine has a wonderful explorer parka, which is built with a drawstring waist that allows you to give the puffer some shape. I love the updated LL Bean feel of that coat. That's available at No Man Walks Alone and, later, Namu Shop, which are both sponsors on this site.

For something less insulating, try a fleece. Patagonia's Retro-X is a genuine classic, although you can also find slightly more directional remixes through Fujito, Monitaly, Manastash, Orslow, and Eastlogue. I also like Drake's Casentino pullover this season. Michael Hill, the company's Creative Director, tells me it's based on an old Boston track jacket he's had for years. "I don't think we've ever been as excited about anything," he says. "As a piece of sportswear, it's a little outside of what we traditionally do. But it's also made from a fabric that has a bit of sartorial history. We think it's a fun jacket to wear out on a ski resort or in the morning when you're getting coffee."