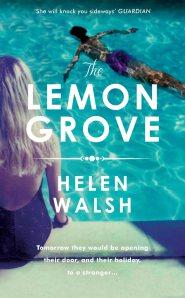

Helen Walsh’s The Lemon Grove is definitely going to be a Marmite book. How you feel about it will probably depend on your tolerance for Forbidden Passion; Madame Bovary is probably a good acid test. Imagine it mixed up with a holiday-from-hell narrative and you’re not so far off this succès de scandale.

Helen Walsh’s The Lemon Grove is definitely going to be a Marmite book. How you feel about it will probably depend on your tolerance for Forbidden Passion; Madame Bovary is probably a good acid test. Imagine it mixed up with a holiday-from-hell narrative and you’re not so far off this succès de scandale.

Jenn and Greg Harding are at the end of an idyllic first week of holiday in their Mallorcan villa. Each year they return to Deià on the rocky west coast for the beauty of the landscape, the luscious food, their stylish accommodation. This year is going to be a little different. Usually they come out of season when it’s cooler, but here they are in the furnace heat of full summer, for Jenn’s stepdaughter, Emma, a precocious and rather spoiled 15-year-old, is flying out to join them with her new boyfriend, Nathan. Jenn and Greg have been together so long that Emma feels almost like the child of their marriage, but there are clearly fault lines of tension that reveal the scars of the family graft. Greg is only a moderately-paid academic, but he will spend lavishly, and somewhat secretively, on Emma. He is a sop for her melodramatic teenage ways, too. Whilst Jenn often feels that Emma’s drama queen antics require a bit of cold treatment, Greg is a willing audience to her every emotion. And of course, Emma is growing up and as highly-strung and volatile as any adolescent; rebellion and rejection are braided into her behavior with her parents.

Things begin badly when Emma’s arrival catches Jenn unawares. She has been sunbathing topless and has fallen asleep, and her groggy attempts to get her clothes on over her sticky skin bring out Emma’s contempt and embarrassment. It’s only much later that Jenn realises the real reason for her anger is that Nathan saw her too. Nathan is a young Apollo with a Manchunian accent and the narrative pants and drools over him: ‘He is wearing a pair of plain blue swimming shorts, otherwise, he is naked before her. He is muscular, but graceful with it, balletic. He is shockingly pretty.’ And thus the plot of the book instantly unfurls before us. Jenn is forty-five and on the cusp of a crinkly middle-age; Nathan is forbidden fruit every which way you look at it, but he’s also gorgeous, virile and apparently hot for her. Yikes.

In all fairness to Helen Walsh this is a great deal better than one might fear. It could so easily have descended into Fifty Shades of Sunburn, but it’s infinitely classier than that. The story moves at an inexorable pace, steadily ratcheting up the tension, so that even quite ordinary holiday-making events like visiting a local market or taking a late-night swim are rimed with an aura of dread. The writing is very good; the rocky promontaries of the coastline, the self-consciously artisanal local stores of tourist regions, the succulent food, the treacherous currents of the sea are all vividly rendered and provide a suitably wild landscape with that hint of holiday dislocation against which strange and unusual things may happen.

The relationship itself is also cleverly portrayed. Walsh doesn’t bother attempting justification: Jenn knows full well she is doing a crassly stupid thing, but she can’t seem to help herself. She loves her husband, but there’s a moment when she looks at him, working at his laptop in the villa:

observing him now in the hard white glow of the desk lamp, his body has never looked so slack, so tired. The loose skin of his chest hangs down as he hunches over the pad. His skin looks lived in; soon he will be like the crones in the backstreets. His pelt will hang from his body like old pajamas.’

It simply isn’t fair. Nathan’s peachy perfection, his taut muscular body and smooth beautiful face are a taunting sensual delight, irresistible. This isn’t about having anything in common, or admiring one another’s good qualities. It’s sheer lust.

As I’ve said before, it’s situational clichés that bother me, and I wasn’t sure how I’d get on with the older woman-younger man thing. Not because I have shockable morals, but because I have a blueprint in Colette’s amazing novel, Chéri, that I didn’t think could be surpassed. This doesn’t come anywhere near Chéri for me, and I did heave a sigh when the climax finds one of the teenagers missing in a storm. But it’s not a bad piece of beach entertainment; a narrative that holds together well, written with a lot of style, and that ends very cunningly. I’ve heard the ending described as ambiguous, but that’s just plain wrong: it’s one of those endings where one small clue tells you exactly what’s going to happen although the narrative stops short of describing it. I thought that was rather good.