A FEW years ago your columnist received an impassioned lecture from the square-jawed owner of a gun shop in Denver, Colorado. Governments, the proprietor noted, have a natural tendency to tyranny; firearms insure individuals against it. The man added that he once lived in East Germany, where he had seen how rapidly the slide can occur, once citizens lack weapons.

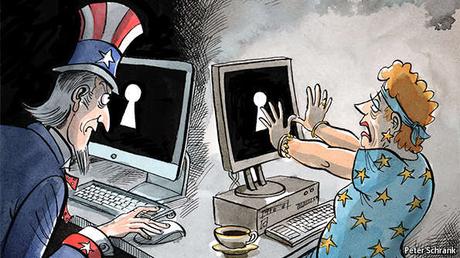

Charlemagne found this unpersuasive, even if, surrounded by assault rifles and handguns, he was too polite to admit it. But the owner’s logic resembles a claim heard in parts of Europe with memories of dictatorship more recent than George III. Tough laws, it is said, are needed to limit the abilities of governments (or firms) to record, store and distribute data on individuals. The specter of the Gestapo is often raised. These concerns, perhaps unsurprisingly, are strongest in Germany.

German and American attitudes to privacy are grounded in different ideas of the relationship between the individual and the state, and encoded in different types of law. In 1970 Hesse, a German state, passed the world’s first data-protection statute. A federal law followed six years later….