When Aaron Watkin was a dancer with the Canadian National Ballet in the late 1980s, he was sometimes overcome with unnerving anxiety. "I felt my body humming with fear," he says. "I would have to say to myself: your solo will only last 60 seconds and then you can leave the stage. Sometimes I think: if I had had a little more support, I might have felt differently."

Watkin and I met in the sleek new east London office of English National Ballet, where he has been artistic director since September following the departure of Tamara Rojo in 2022 after a decade at the helm. Rojo, now artistic director of the San Francisco Ballet, left behind an intimidating legacy: under her visionary leadership, the ENB transformed itself into a European powerhouse with a revolutionary repertoire at its core.

Yet her reign has been marred by unsubstantiated claims of bullying, while the wider ballet world is currently reeling from a series of sexual abuse allegations and revelations about eating disorders and mental health that have exposed the ugly core of this most exquisite of art forms. Add to that a challenging financial climate, a rapidly changing cultural landscape and the persistent misconception that ballet is an exclusive art form, and Watkin, 54, faces a daunting task. "ENB is in fantastic shape," he says in his light Canadian accent. "But there is no doubt that we need to work hard to change perceptions."

Earlier this week, Watkin announced the company's 75th anniversary programme, which includes a new production of The Nutcracker, the first for the company in 13 years (ENB's current version of this beloved Christmas play was seen by 75,000 people at last year's London stage at the Colosseum only). It's a powerful statement of intent, affirming ENB's commitment to the classics while recognizing that an 1892 ballet can once again speak to a modern audience. What can these target groups expect? 'A sugar plum fairy, for example [the fairy doesn't appear in the ENB's current version]," says Watkin. "Oliver nominee Arielle Smith is co-choreographer and will bring a fresh theatrical spectacle to the Prologue and Act One. But we also reconsider Clara's role. She's not just a cute little girl that everyone follows."

The story continues

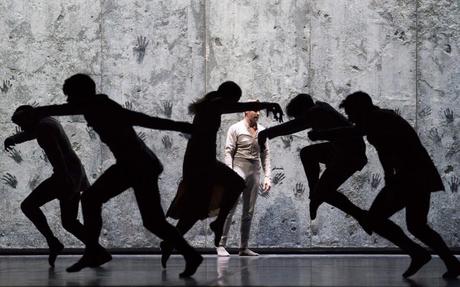

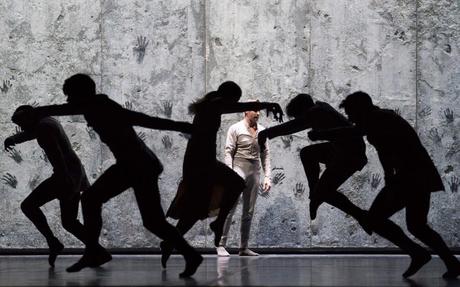

There will also be a new William Forsythe program with a world premiere - a project close to Watkin's heart, having collaborated extensively with Forsythe throughout his career, first at Forsythe's invitation as principal dancer at Ballett Frankfurt and later with the placement of a number of his ballets with various companies around the world. He has also revived Akram Khan's impressionistic adaptation of Giselle, relocating the 1841 original to a modern migrant community, and will tour next year with a revival of Mary Skeaping's traditional 1971 production.

Watkin isn't interested in jettisoning classics simply because they might reflect outdated values or storylines. "You can't move forward unless you know where you've been," he says. "To simply get rid of something, yes [too] simple. Instead, you look at how you can reinterpret them to represent them better. There are beauties in both versions of Giselle. You don't have to choose."

His main commitment, however, is diversity. It's a word that threatens to sound meaningless, but although Watkin can sometimes sound like he's swallowed a management language manual, he has worked extensively with modern and classical companies (before joining ENB he was artistic director in Dresden, where he radically modernized the repertoire) and passionately believes that when it comes to body shape, the former can refresh the latter. "I'm not looking for a harmonious look where everyone looks the same," he says. "I am interested in individuals and personalities, although they must of course have the physicality that a dancer needs." His inclusivity ethos naturally extends to trans and non-binary dancers. "I haven't come across a trans or non-binary dancer yet, but if I did, we at ENB would sit down with them and discuss how we can best support them."

Still, he admits that certain attitudes will be difficult to change. For example, the influence of George Balanchine, the New York City Ballet choreographer who preferred his female ballet dancers to be leggy, thin and preferably hungry, remains deeply ingrained in the ballet psyche. "Many people in the culture grew up with a certain physical ideal. The more traditionally minded are bound by the idea that certain characters must be small, innocent-looking blondes. But not every Giselle has to be vulnerable and small. It's not just little women whose hearts are broken."

He is also optimistic about the classical corps de ballet, which traditionally promotes a uniform body aesthetic. "It's a matter of being inventive. If I were doing a classic production of Swan Lake, I would make sure the littlest girls sat at the front and that the line moved naturally up to the top. Hopefully we'll get to the point where there will be so much diversity on stage, that different forms won't stand out, but will all blend together."

The prevalence of eating disorders in British ballet schools, as revealed by a Panorama survey last September, did not shock him. "When I was younger, these things weren't discussed as much," he says. "There wasn't much emphasis on the mental and physical support a dancer needs." He points out that at ENB, as is now the case with ballet companies around the world, systems are now in place to ensure dancers have access to help. So if a dancer had to survive on a packet of chips at lunch, he would know about it? "Yes, but at ENB we have an artistic mentor with a background in dance and psychology who works privately with dancers to help them manage anxiety and body confidence."

What about bullying? Did he encounter it? "Historically, companies have been managed from the top down. My teachers told me, 'that's the way it is, shut up and take the step'. But you can no longer say that to a young dancer, because he says: 'I don't have to do that'. You have to get contemporary dancers on board in a way that makes them want to participate. In my time, artistic directors didn't have to think outside the box. Now you have to keep up with the world and evolve with the generations."

Of course, it is crucial to make those new generations believe that ballet is primarily for them. We look around at ENB's sparkling new office spaces, ambitiously located in Stratford, a relatively deprived part of East London rarely visited by the culturati. "I am committed to increasing our presence here," Watkin said. "Those who find ballet elitist and boring do not come to us in the Colosseum. That's why we have to go to them."

Watkin got into ballet almost by accident, after taking tap dancing lessons with his sister on Vancouver Island at the age of twelve. A teacher saw his potential and soon he was studying at Canada's National Ballet School in Toronto, returning home only once a year because his parents couldn't afford the trip. 'I was terribly homesick, but I am forever grateful to my mother for insisting that I stick with it. Otherwise I probably wouldn't be here today."

For more information about English National Ballet's new season, visit ballet.org.uk