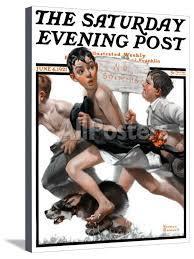

On Labor Day we visited the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, MA. Rockwell was an “illustrator” who disclaimed producing “fine art.” And some see his oeuvre as a mythologized, sanitized, saccharine picture of a past America.

On Labor Day we visited the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, MA. Rockwell was an “illustrator” who disclaimed producing “fine art.” And some see his oeuvre as a mythologized, sanitized, saccharine picture of a past America.

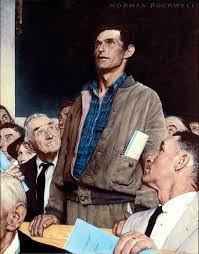

Yet what is art if not an image that elicits an emotional response? And Rockwell’s pictures are not false. To the contrary, they show us some truths about human life. While cynicism is fashionable, there is reality in Rockwell’s vision. His work reflects a deep love for his fellow humans. And an emotional response was certainly forthcoming in me.

Looking closely, I was struck by how insightfully Rockwell captured facial expressions. His pictures were generally set-pieces almost akin to cartoons. Yet the characters portrayed were not caricatures or archetypes; rather, real people, caught in real moments. I soon found myself looking at fellow museum visitors and imagining them as painted by Rockwell.

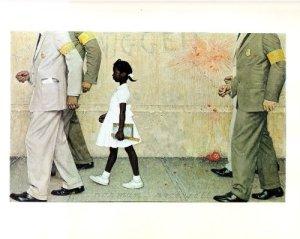

And about that idea of a sanitized America: I noticed an explanatory label mentioning that Rockwell was once forced to paint out an African-American on a magazine cover because you could only portray blacks in menial roles. However, later in his career, Rockwell felt free to be forthright in addressing the race issue in his paintings.

One point I noticed is that Rockwell’s black children were always immaculately dressed: painted with respect.

Afterward, in Stockbridge, we stumbled upon the little Schantz Galleries (3 Elm Street, “behind the bank,” the sign says). The ground floor had a display of Chihuly glass art. Nice enough; but upstairs: WOW! Also all glass art, but absolutely amazing. Remarkably too, by a large number of different artists.

Making me feel exalted to be human.

Advertisements