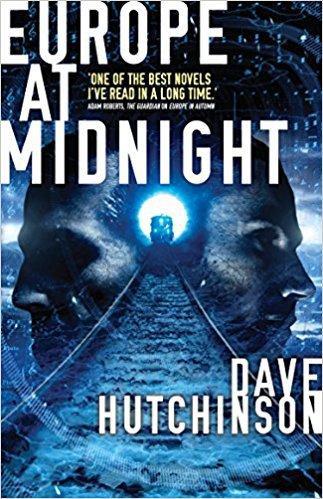

Europe at Midnight, by Dave Hutchinson

I read Dave Hutchinson’s Europe in Autumn back in the summer of 2016 and was distinctly impressed by it. First of a trilogy, but standing perfectly well on its own, Autumn was original and intelligent science fiction with strong contemporary resonances.

Midnight is more obviously part of a series and is inevitably a bit weaker for that. However, it’s still an extremely enjoyable piece of SF/spy cross-genre fiction and still has plenty to say about current UK obsessions.

Midnight opens on the Campus – a strange society consisting of nothing except a vast university. It’s recently had a successful revolution deposing the old regime who had efficiently but brutally run the place for as long as anyone remembers. It’s quite clearly not our world but its inhabitants are unaware of any other.

The Campus is a sort of 1950s-ish Tweedy England shorn of any context. Everyone bicycles (they have no knowledge of cars); social status is hereditary; technology is comfortable and unintrusive. It’s a sort of dream of Englishness but not a sustainable one. The food’s running out. There’s no trade as there’s nobody to trade with. Anyone who tries to leave is killed by seemingly ubiquitous surrounding booby-traps. The place makes no sense.

The main protagonist of Midnight is the new head of intelligence at the Campus, previously a lecturer in the English department. His main goal is to find some way of escaping the place to the wider world he believes must exist. Beyond that he’s trying to understand the realities underpinning the old guard he’s replaced. What he finds is a horrific underbelly of secret police and unregulated human experimentation. Those responsible for the horror were of course all thoroughly good sorts. Here’s the Dean of the Science Faculty, a rare survivor of the old regime:

He was about five years older than me, and he had the clean, well-exercised look of a man who plays a lot of team sports and is rarely on the losing side. His hair was thick and brown and curly and touched a little with gray at the temples, his clothes discreetly expensive-looking. He radiated masculine bonhomie like a nicely bedded-in coal fire.

The intelligence head’s name isn’t given but he’s known to a friend by a literary nickname – Rupert of Hentzau – which he reuses after he finally escapes. That’s as close to a real name as we ever learn. He finds his way out and emerges in real-world London where he promptly gets stabbed on a bus. He survives but comes to the attention of our own intelligence services and from there it’s a classic spy novel of scheme and counter-scheme.

Rupert is that classic spy novel character – the man who knows too much. He is living proof of the existence of nested parallel Europes which can be reached from our one if one knows the route. The Campus was a pocket reality, embedded in another pocket reality known as the Community which in turn is embedded in the “real” Europe. The Community is the only one here with all the facts – both the Campus and our Europe are ignorant of it – and it’s willing to kill to preserve its power and anonymity.

The Community originated in England as part of real history before splitting off to become its own reality. Now it maps across most of Europe but with no neighbours or indigenous peoples to get in its way. It is the colonial dream of a certain kind of English xenophobe made (alternate) reality.

Everyone in the Community was English. From one end of the Continent to the other. There were only English things here. There were no other languages, only regional dialects. No other cuisines but English. No other clothing styles but English. No other architectural styles but English. It was awful.

Much of Midnight takes place in the Community with Rupert infiltrating it on behalf of real-world British intelligence. It’s an interesting setting but creates an issue for Hutchinson since one of the Community’s most telling features is that conformity carries a price:

In two hundred years, the Community had not provided a single playwright of any great note or a film which would have troubled an Oscar voter for more than a minute.

This means that a large part of the novel is set in a place that intrinsically is a bit dull. The Campus was based on the Community and while the Community is more technologically sophisticated it too is a highly conformist 1950s-ish Sunday-night-TV-drama sort of England. It’s a sharp contrast to the complex fractured Europe of Autumn.

The Community does allow Hutchinson to explore certain ideas of Englishness and their underlying historical reality. In the real world 1950s Britain was still a colonial power, even if a quickly fading one. Behind the cosy imagery of cricket matches in country villages and social deference was a system maintained overseas through violence and political oppression.

I read Somerset Maugham’s Ashenden recently and very much enjoyed it. I’ve also read some of his Far Eastern Tales short stories. Maugham makes no bones about the bloody underpinnings to Colonialism and British power (nor does he see it as anything to apologize for). Maugham, like many of his contemporaries, accepted that British dominance carried a price for those dominated.

With the Empire now gone there are those who like to pretend that it was all an act of altruism; that we went out into the world to give people efficient civil services and well-run trains rather than to get rich. Maugham and his peers would have seen that for the self-serving fantasy that it is.

The Community is another exploration of that myth. They are the England some want the real England today to become. An imaginary place where everyone knows their place and foreign influences are neatly swept away. It’s no accident that this dreary status quo is preserved with unhesitating ruthlessness.

All that works pretty well. Less successful are some elements of the contemporary (i.e. future) real London in the novel which feels pretty much precisely like London today. Autumn is set in a future Europe devastated by plague and war but Hutchinson’s future London isn’t remotely changed. The buses still have operator-drivers as they do now, people still get take-aways in Burger King, flatshare and go to work in the usual fashion.

It’s possible of course that Hutchinson felt that a strange future London would make the whole novel too distant when coupled with the Community and the Campus. It’s also fair to say that the contrast of the Community works much better when put against a London which remains recognisable. Still, it’s odd in an SF novel to have a future that’s quite so much of the present.

Another slight oddity is that Hutchinson’s characters aren’t as diverse as his setting which here is an issue as the book is in part a critique of conformity. Female characters tend to be secondary (Hutchinson has in fact recognised he needs to write better female characters who exist as more than plot supports for the male so this should improve). Future London is largely a place run for and by straight white men. Admittedly, depressingly, that may be realistic.

The result is a novel that isn’t quite so dazzling as was Autumn. The future London is a bit too much present-day London and some improved female characters wouldn’t hurt. For all that I still really enjoyed Midnight and I’m definitely planning to read the third of the trilogy before too long.

Other reviews

This review from the rather wonderfully named Battered, Tattered, Yellowed and Creased blog is a bit more positive than mine and I think largely fair. I was very impressed by this review from Strange Horizons which explores issues of diversity in the novel much more than I did (I don’t necessarily agree that the novel would have been better for a wider range of diverse figures such as, say, gay characters but I think the point and argument are both well made). It’s a very good critical piece.

Lastly, not a blog but Paul McAuley reviews it here at the New Scientist interestingly comparing the novel to Eric Ambler which I didn’t think of but wish I had. No idea why they describe McAuley as an SF blogger given he’s actually a pretty highly regarded SF author in his own right.

Filed under: Hutchinson, Dave, Science Fiction Tagged: Dave Hutchinson