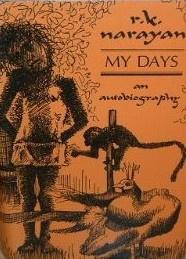

Book review by Sue Roe: I hesitate to say this but I had never heard of Narayan. He was a well-known (if not to me!) Tamil Hindu, a writer of over 200 novels, as well as plays and short stories.

His memoir, written in 1974, was an easy read and very enjoyable.

It records his early life in Madras, living with his uncle, a photographer, and his grandmother, whilst his mother and his siblings lived in Chennapatna where his father was headmaster. He had a succession of pets, a peacock, a mischievous monkey, a kitten and finally a puppy but they all died. On visits to his family in the holidays, his brother taught him how to trap and train grasshoppers:

“We…tried to teach them tricks but invariably found them dead two mornings later”

He attended a series of schools- initially the Lutheran Mission School. Here the teachers were Christian converts who were hostile to teaching non-Christian pupils especially a Brahmin like him. However, his grandmother noted his lessons and taught him herself. He was not especially academic: he was not interested in learning:

“Going to school seemed to be a never-ending nuisance each day”

He preferred writing his stories, exploring, playing football with his friends. After attending two other schools, he transferred to his father’s school in Mysore. During the holidays he read the library’s magazines: The Strand, The Manchester Guardian & the Times Literary Supplement. Fascinated by Walter Scott after reading The Bride of Lammermoor, he read six more of his novels and moved on to Dickens, Rider Haggard, Marie Corelli, Pope, Marlowe: “An indiscriminate jumble.”

He loved tragic endings:

“Thus, Mrs Henry Wood’s East Lynne left me shedding bitter tears and read it again and again”

He passed the university entrance exam at the second attempt and studied History, Economics & Politics. His father tried through his contacts to get him a job: in banking and on the railways. After a short- lived career in teaching, he turned to writing fulltime. His most famous novels include Swami and Friends (1935), The Bachelor of Arts (1937), The Dark Room (1938), The English Teacher (1945), Mr Sampath (1949) as well as collections of short stories. These took place in his fictional village of Malgudi. The publication of these books was helped considerably by the friendship of Graham Greene who had been given the manuscript of Swami & Friends by a friend of Narayan.

The memoir recounts details of his love life too; after a few adolescent crushes, he met his future wife, Rajam. Despite the objections of her father on the grounds of an unfavourable horoscope, they were married. She sadly died on typhoid in 1939 at which point, he went to pieces, stopping writing. After a spiritualist experiment, involving automatic writing, he became convinced that he could be in touch with his dead wife.

His writing career was interrupted by World War Two and the shortage of paper. To make money, he wrote for The Hindu newspaper and started a short-lived magazine of his own: Indian Thought.

In 1956 he obtained a Rockefeller Foundation scholarship and spent time traveling in the USA where he wrote The Guide (published 1958).

The book ends with Naryan living in Mysore, trying his hand at farming a plot of land, listening to radio programmes,worrying about municipal shortcomings and discussing the state of the world with his brother.

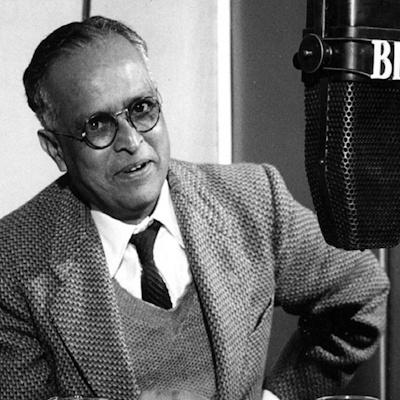

R.K. Narayan

R.K. Narayan

His writings often include details of his own life. Swami encounters hostility from his Christian teachers. In The Bachelor of Arts, the most autobiographical of his works, the lead character falls for a 15-year-old girl but her parents oppose the match on the grounds of an unfavourable horoscope. The eponymous English Teacher marries but his wife dies of typhoid. Like Narayan, he is consoled by messages from his wife received via automatic writing. And his experience of writing for film is reflected in Mr Sampath.

As others have noted, there is a Dickensian feel to his writing. The recall of his childhood through the eyes of an adult reminded me of Pip in Great Expectations looking back at his first meeting with Miss Havisham, and David Copperfield’s recalling his experiences in the blacking factory. Moreover, as in the works of the Dickens, there is a series of memorable characters who appear only briefly in his recollections.

As he said: “Life offered enough material to keep him continuously busy”

He creates characters who feature once and then are never heard of again, such as the lamp lighter and Kokandam, the fuel merchant. The latter, fierce and an expert with the bamboo pole, inspires such fear in Narayan that he hides himself for hours, driving his family to distraction, who eventually call in the police. He finally emerges but refuses to answer any questions. As he says:

“In childhood, fears and secrecies and furtive acts happen to be the natural state of life, adopted instinctively for survival in a world dominated by adults.”

His uncle is a member of the university drama group and entertains the boy with his re-telling of The Tempest. This reminds me of Mr Wopsle in Great Expectations who has theatrical ambitions.

At school he drifts through his classes and remembers few of his teachers, apart from Professor Rollo who taught Shakespeare, the Indian history teacher, Professor Venkateswara and Professor Toby. The last never read the roll call as he could not pronounce the Indian names and never looked at his class:

“For many years it was rumoured that he [Toby] thought he was teaching at a women’s college, mistaking the men’s dhotis for skirts and their tufts for braids.”

After graduation, his father’s attempts to get him a job provide some of the most comical incidents. When Narayan goes to meet the Chief Auditor od Railways, he is met by a comical sight:

“The gentleman was bare-bodied and glistening with an oil-coating as he prepared himself for a massage; he blinked several times to make me out, as the oil had dripped over his eyes and blurred his vision.”

A visit to a banker friend of his father conjures up an equally amusing scene:

“This man, though not oily, was also bare-bodied (everyone seemed to be shirtless in Madras) … He was …sitting on a swing, while I kept standing. It was difficult to carry on a conversation with him as he approached and receded…I had to adjust my voices to two pitches to explain my mission and also step back when the swing came for me.”

There is little that is overtly political which is surprising considering the campaigns for Indian independence in the 1920s and 1930s. His recollection of his time as a scout does touch on the subject. When he was at high school, he was a keen scout and was a member of the B.S.A – the Annie Besant Scouts of India. (She was its president and a champion of Home Rule for India.)

“I… proudly revelled in an exclusive world of parades in khaki shorts, double pocket shirt, green turban, gaudy scarf and bamboo staff in hand; we saluted each other with the left hand… Our three fingers …. Were supposed to symbolise this triple loyalty to God, Crown and Country. But alas what a miscalculation… our uplifted fingers indicate an oath to serve not God, Crown and Country but God, Freedom and India.”

I enjoyed this memoir especially his descriptions of his childhood and the evocation of the landscapes of Madras and Mysore. His writing is fluent and full of humor and humanity; his descriptions of people and place are vivid and convincing.