Having fallen headlong in love with sculpture, I resolved to start studying it upon my return to Brisbane. And so, once a week at the Atelier, Ryan has been teaching me about the literal moulding of form, about the three-dimensional finger-painting that is sculpture. I’ve been amazed at how I can ‘draw’ lines with my hands, lines that undulate as I circle my piece, and how I can work with the shapes of tones much as I would when drawing or painting.

I’ve struggled with the three-dimensional puzzles of lips—how the extremities of the profile must restrain the apparent swellings from the front; how the lips wrap around the teeth deeply into the cheeks; how the nodes at the sides collect everything in little fleshy pockets that leave expressive little indentations at the corners of the lips.

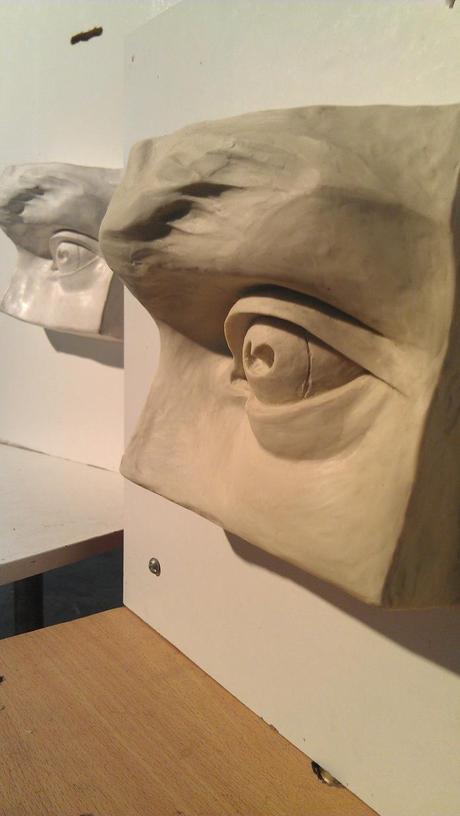

I’ve physically constructed the riddle of the bony eye socket, not a simple rectangle sloping back under the eyebrows, but simultaneously wrapping back around the head and reaching out to the crucial cheekbone turning point where front sharply becomes side. I’ve agonised over s-curves buried in facial furrows and shaped the thickening and thinning c-curves that spiral deeper than you ever first imagine.

Every slope you trace, observing its horizontal and vertical axes, moves backwards or forwards at the same time, its trajectory changing drastically as you circle to another viewpoint. The game is to try to conceive the whole, not a slice. The lesson of sculpture is that everything is doing more than two things at once.

Holding each facial feature in your hands, forming them from sticky lumps of plasticine, is a pretty thorough way to get your mind around them. Rather than reaching for generic shapes, you begin to build up in your mind an actual object, a complex three-dimensional form, that takes on various guises as it moves around. You don’t simply reach into your brain for that eye shape to fill that gap, but rather you grow to an awareness of how an eye socket shapes part of the head and how an eye slots into it, strapped in by thick and very-present eyelids. The face ceases to be an oval waiting to be filled with ‘the interesting bits’ like a china plate ready for its ornamental flowers. It begins to come together in your mind as voluminous bricks that lock into each other—some deep, some protruding, some spiralling, some tucking under.

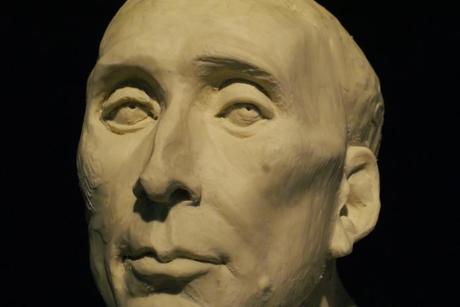

Having worked and reworked the masses, adjusted the placement of the features, sliced off and reattached an ear, grown the back of the head and massaged the trapezius and sternomastoids into an elegantly twisting neck, the pure delight of modelling the surface brings new challenges in the form of new expressive ideas. Juggling in your mind the knowledge of the softness of the skin of lips, the firmness of cartilage and the immovable frame of bone beneath, finding a way to express these structural differences in the treatment of the surface is mind-bending and infinitely expressive. The touch of your fingers leaves a different trace than that of hatching with wooden tools, and the art is in folding these strokes into each other in meaningful ways. These final caresses breathe unimaginable life into the sticky mass, small refinements seeking out the character of your subject and approaching a likeness by a means surprisingly removed from sheer accuracy.

One would imagine drawing is a practical enough way to approach the world—better than solely reading about anatomy, or cursorily looking at the world around you, for it taxes your motor skills. And yet, once you begin to sculpt, you realize the sheer kindergarten delight of kinaesthetic learning. Drawing, all this time, has been trying to find a shorthand for this grappling with mud. And the new battles of sculpture feed directly back into drawing, cementing spatial concepts and freeing us just a little more from a deep-seated reliance on shapes and outlines.