‘Vacuous!’ said Mr Litlove. He closed the book of essays and let his head fall back against the couch, wearied by his reading. ‘If you’d written that, I’d be giving you a hard time.’

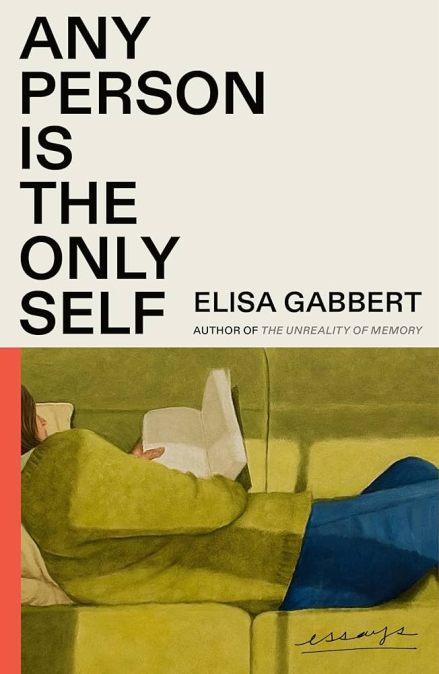

The book in question was Any Person Is the Only Self, a collection of literary essays by the American writer Elisa Gabbert, and I was rather enjoying them. I’m obsessed with literary essays at the moment. This all began with Amina Cain’s A Horse in Winter, which I read while we were in Somerset. I’d never come across anything like that book before, and I’m not even sure I can legitimately use the term essay for her loose, meandering, beautiful, vivid, untitled explorations. Cain was turning to books and paintings she loved in order to examine certain kinds of tropes and strategies in art, considering what effect they produce on the audience. She would use up the potential of a whole book in a couple of sentences. A whole book! I sat reading such textual profligacy with saucer eyes, wondering to myself – you can do that? Everything I’d ever done with books involved a deep dive into the material. I was used to words like rigorous and exhaustive being the good words, the qualities you wanted to achieve; but now they just sounded tiring. Cain could take one example from a book and throw away the rest, she could skim through her mental Rolodex of artworks and produce something that felt calm and lucid and peaceful. Not trying too hard, I guess.

Here’s the thing about stories – they are the only form that encapsulates the entirety of life – how we live, what the world is like, how we react to every situation that may arise. Every other kind of study only concerns a part of the whole. Zola thought the novel was a kind of laboratory in which any combination of personality and crisis could be tested and its outcome determined. It doesn’t quite work as a theory because a novel is a rigged game, but the idea lingers. The novel contains what is, what was and what could be; in its duration it has the elasticity for loss and change. We are creatures of language, both in terms of what we can say about ourselves and what we can’t, and the lacunae offer spaces where art is born. What I’m trying to say is that a story contains such richness, and it does so many things, that I end up wondering why I’m writing the same sort of stuff about each book I read. Basically, this is why I gave up reviewing for so many years. I never got bored of the books, and I never got bored of other people’s reviews of them, but I got bored of myself. Here I came, trotting through the landscape of a story, pointing out some interesting landmarks along the way, summing up intentions and themes like a good package tour guide, stuck on the same old loop, ad infinitum. I used to think that so long as I had different landscapes to describe, it would be enough. And then it wasn’t. I felt the way I did when my seven-year-old son finished his first game of Snakes and Ladders, sat back on his heels and contemplating the board asked me, ‘What else does it do?’ I had no answers, then or now.

So Amina Cain was the start of a picaresque journey into the world of the literary essay. I decided to watch other minds as they thought their way around a story and what it offered them. But I’m aware of my tendency to second guess and overthink. In other words, every Don Quixote needs a Sancho Panza, and so I roped in Mr Litlove. Mr Litlove likes to read out loud. He likes to do this as we sit with a cup of tea on the couch after lunch, procrastinating about the afternoon. These days we run the risk of him reading us both to sleep; such are the features of middle-aged peril. But Mr Litlove is the biggest challenge to find books for – he’s critical of everything. I wasn’t going to fall into the trap of loving innovation for its own sake with him by my side.

Which brings us to Elisa Gabbert and Any Person is the Only Self. I read a couple of these essays before I got Mr Litlove involved and I’d been very favourably impressed. Gabbert’s roster of favorite authors looks a lot like mine – Sylvia Plath, Virginia Woolf, Rainer Maria Rilke, Proust. One essay talked about founding the Stupid Classics Book Club, which was not a club for stupid books, but for books that its members thought they knew all about from a ton of cultural references, when in fact the book was entirely different. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein featured highly. She wrote about party literature, from Gossip Girl to The Great Gatsby (which made me want to write the British version, from the Barbara Pym church tea party to the awkward, even disastrous dinner party beloved of novelists like Ali Smith). She wrote about madness in literature, and uncanny children, and writers’ relationships to their diaries. She also wrote a lot about her own life, though in a quiet, unshowy way, discussing – hilariously – the rage of reading something one wishes one had written oneself, and a lot about the experience of lockdown, with which she struggled. She even had her own Mr Litlove, her husband, John. I related to these essays, in other words, and I admired her smooth, easy writing style.

But Mr Litlove had other opinions. One essay ‘Somethingness (Or, Why Write?)’, had Gabbert moving swiftly through the motivations and preoccupations of a dozen or more writers in quick succession. ‘It’s like she’s got hold of a biographical dictionary,’ Mr Litlove grumbled, ‘and she wants to put in all the quotes.’ In ‘Against Completism’, Gabbert talks about the experience of reading an unpublished short story by Sylvia Plath. This makes her think of her initial reluctance to read The Bell Jar in case it wasn’t as good as the poetry, though when she did, she loved it. She calls it a ‘metafictional’ novel, a novel about writing a novel that reminds us novels are constructs made of words ‘not a rubric for something nonlinguistic, the way some novels feel like novelizations of the movies they hope to become.’ This makes her excited for the short story and she reads it, but she’s disappointed: it isn’t good. She tells her husband about this later, and he talks about Nabokov’s unfinished novel that he didn’t want published but his son published anyway. And she has a think about posthumous publication and its pitfalls. Gabbert points out that we now have an enormous amount of writing available by Sylvia Plath and says she doesn’t want to read all of it. She talks about the index to her journals, which has topics and references in wild, unexpected abundance, and that she wants to save some treats up for later – what Plath thought of Marilyn Monroe, for instance. And that’s where it ends. Mr Litlove really didn’t like that one, unsure what the point was. ‘I feel I’m being made to do a lot of hard work for very little reward,’ he complained. though in fairness everything in the essay had been against completism, as the titles suggested.

This made me think more deeply about the form of these essays by Gabbert. They are very metonymic – one idea leads to another and to another in a chain of associations. So you can end up in a different place to where you began, often circling an idea but without reaching a conclusion. Her best points are often made in the first page – ‘For Plath, success was a lifelong skill in itself, separate from writing’ – for instance. ‘Classic party fiction is often, if not always, a kind of wealth porn.’ But there’s nothing to correspond to this at the end. Most of the essays trail away – the literary breadcrumbs run out. Of course Mr Litlove wouldn’t like this. He’s all about the takeaway. He likes to have his points nailed and for there to be interesting aha! moments that make him feel like he’s learned something. He wants something solid in return for the investment of his time. But I think Gabbert’s essays are evocative and suggestive, and entirely free of the pedagogic urge. We do watch her mind at work, as she follows her own kind of golden thread through the labyrinth of literary possibilities, and she’s very interesting en route. But if you want more than that, then it’s your own mind you will see working. And for me, I found there was a certain lightness to that, an ease of mental movement, a freedom from intellectual processing. They were very easy to consume, these essays, and when I finished one, I was already ready for the next. I wish she had several volumes of similar essays available, as I would order them and gobble them down. But can I remember now anything much of what I read? Not really.

Is this, then, where literary essays are going? I feel a family – or perhaps a generational – similarity between Elisa Gabbert and Amina Cain. They both make this business of thinking about literature very easy and yet also very expansive. They cover a lot of ground and they restrain themselves from being too clever. They are interested in all their responses to art, emotional ones perhaps more intensely than rational ones, and remain informal presences in their work, offering a kind of conversation with a charmingly thoughtful friend. Well, this was how I was thinking, and then we began Mary Gaitskill’s essay and oh boy, are they different. But enough for now. I’ll talk about them another time.