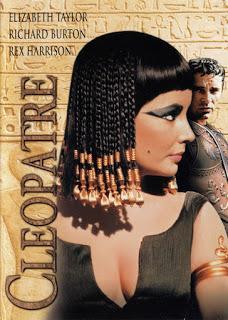

As critics and cinephiles bemoan the arrival of the latest Transformers film, it's probably as good a time as any to reflect on Hollywood's history with the "bigger is better" mantra. This week I took on the daunting task of watching 1963's "Cleopatra", a big budget epic starring Elizabeth Taylor that runs nearly 4 hours. Much like today's blockbuster obsession, the film was part of a trend of large-scale visual spectacles dominating the box office (at the time these were mainly lavish musicals and historical epics). History seems to be repeating itself then, as "Cleopatra" is known for its striking visuals that mask the shortcomings of its script.

"Cleopatra" is perhaps best summed up by a pair of quotes found within the film itself. Together they concisely capture the film's strong points, as well as its nagging flaws. It's a pity that Joseph L. Mankiewicz (director and co-writer) wasn't self-critical enough to craft a more compelling film.

The first quote comes very early in the film. Julius Caesar (Rex Harrison), a Roman general and Cleopatra's initial paramour, goes to meet the young Pharaoh Ptolemy XIII in Egypt as part of war negotiations. Upon arrival, Caesar approaches the Pharaoh's entourage and quickly makes note of these curious people. Noticing their elaborate attire, he exclaims "You all look so impressive. Any one of you could be king." This is delivered as a throwaway scoff, but it turns out to be an almost self-aware acknowledgement of the film's Modus operandi. Much of the film's value is derived from its impressive visual spectacle, a quality that hasn't diminished over the years. The production design is staggering to behold (filmmakers wouldn't dare to construct all those elaborate sets today). A grand procession for Cleopatra in particular can only be described as "monstrous". Perched atop a giant Pharaoh float, pulled by hundreds of servants, it's a scene that defines the film's audacity (and it's record-making budget).

Likewise, the impressive costumes mentioned earlier are also awe-inspiring. The main attraction of course, are the outfits (about 65 costumes in total) given to the film's titular character alone. Costume designer Renié did some truly remarkable work, clothing Elizabeth Taylor in stunningly flattering gowns that left no doubt as to the notorious sexual allure of Cleopatra, as mentioned by the men in the film.

So where did this visual feast falter? The second insightful quote (uttered during that same extravagant procession) would seem to address this. One of Caesar's right-hand men remarks to him, "The queen has given instructions for the procession to move as slowly as the people wish, for their full enjoyment." Presumably unintentional, this line reflects the film's "double-edged sword". Indeed, there's much enjoyment to be had in the showmanship of the production values, but the bottom line is that the film becomes increasingly slow and tedious. After the climactic events surrounding what is popularly known as the Ides of March, the film struggles to sustain any momentum. Much of the second half involves indoor political scheming and the actors (namely Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor) fail to elevate the dull material. By the time we reach the Battle of Actium, the film has already lost most of our interest.

Taylor in particular is egregiously shortchanged by the script. Quick historical research would indicate that Cleopatra was legendary for her political acumen, yet the film relies more on the sex appeal which allowed her to align herself with powerful men. Taylor is certainly very striking and attractive in the film, but she never convinces you of her leadership skills. Whether that's the poor writing or just her failure to fully grasp the character is up to interpretation. Either way, when such a major film is dedicated to the presumably extraordinary life of a historical world leader, one would expect to see more than just confidence and cleavage.

When all was said and done, the film was a box office hit, but its massive budget almost bankrupted the studio. Of course, Fox was soon saved by the success of "The Sound of Music" but the stain of "Cleopatra" still lingered. As Mark Harris pointed out in his superb book "Pictures at a Revolution: Five Movies and the Birth of the New Hollywood", even the filmmakers of films like Cleopatra felt uncomfortable defending them as creative enterprises. Suffice it to say, the seemingly contemporary outcry over "the death of cinema" has probably been going on for decades. The blockbuster factory is just a by-product of Hollwood's profit-making business model. It may not promote great "art", but it seems to satisfy the consumers. Today's "The Lone Ranger" is yesteryear's "Cleopatra". Even in their failures, there's something appealing about them. As someone on twitter explained to me, "Cleopatra" is a must-see for the sheer spectacle.