Four years later, My So-Called Secret Identity has expanded to four print volumes, and the whole story is still available free online as we always planned. The art team is still dominated by women - Suze Shore, Samantha LeBas, Ursula Dorada, Jennie Gyllblad, Angela Sprecher - and I share the writing credits with new authors, who submit stories from their own cultural experiences - for example, as a black woman, a trans woman, or a British Asian woman. As a white male writer, it was important for me to offer a platform to others who could tell those stories better than I ever could.

Warner Bros has announced that Joss Whedon will be directing a new Batgirl movie. On one hand, I'm delighted, because the superhero genre needs more leading women, and Batgirl is one of the most undeveloped but deserving characters in the DC Comics universe. But I'm also wary, because Batgirl has already taken more than her fair share of abuse over the years, and I really want to see her treated with respect.

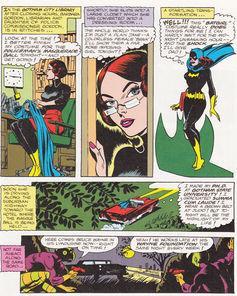

First introduced in 1967, Barbara "Batgirl" Gordon spent 20 years as a token figure of women's liberation before being violently retired in 1988 in Alan Moore's notorious short story The Killing Joke, in which she was shot in the spine and paralysed, then sexually assaulted by the Joker. Having been transformed into the computer expert and information broker Oracle - her disability making her a different kind of icon - Barbara was relaunched as Batgirl in 2011, in full costume and with the use of her legs restored.

My relationship with Batgirl began when I finished with Batman. If that sounds like a break-up, that's also how it felt: I studied Batman for my PhD, and three years of obsessive connection with the Dark Knight became my first book in 2000. After a long break, I wrote another book in 2012 on Batman's 21st century incarnations. By that point I was done with Batman. So I started researching Batgirl, and wrote a few articles about her unrealised potential.

Batgirl, from her

Like no PhD I know

first appearance onwards, was also a PhD student, but never really seemed like one. One autumn day, I led a class for new doctoral students. As is often the case in the humanities, they were all young women: diverse, demanding, enthusiastic and incredibly intelligent. They were nothing like Batgirl.

During the lunch break, I wandered down to the local comic shop. The covers of the comics were glossy. The costumes on the covers were glossy. The women on the covers were contorted into cleavage-exposing, soft-porn poses. The young men running the shop looked up from their games console and stared at me as if I'd walked into their house. I walked out without buying anything. If I, a fortysomething, male author of Batman books, felt unwelcome in their shop, how would the average young woman feel?

I began to feel that if Batgirl was a PhD student, then she should be written like one. And so I set about building a better Batgirl. Rather than criticising comics from the outside, I decided to try making my own, to show how it could be done differently - and done better.

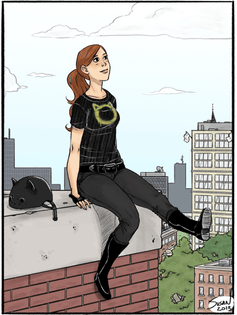

I wrote scripts and commissioned art from almost entirely female creators in order to reverse the usual male-dominated dynamic: one of the illustrators was my former PhD student Sarah Zaidan, the other artist Suze Shore. The idea was to re-imagine Batgirl as an incredibly intelligent young woman, living in a shared house in a hip, arty neighbourhood, and piecing together her costume from the kind of thing you could find in local shops - black boots, a ribbed sweatshirt, a rucksack. Her logo was yellow paint, sprayed through a stencil.

But I realised the project could be bigger than just a hypothetical example of what comics could be like. I changed it to become its own story, with its own characters in its own world, and launched it online as Four years later, My So-Called Secret Identity has expanded to four print volumes, and the whole

My so-called secret identity

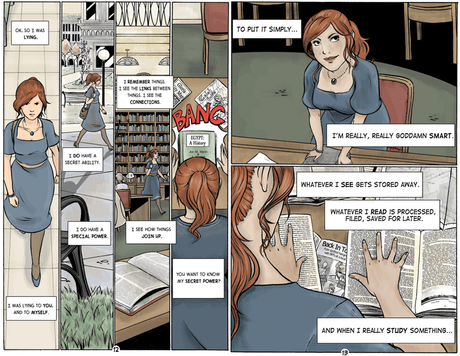

How did we create a character so different from other superheroines? It was radically simple: we wrote and drew her as a normal human. Cat isn't incredibly fit, or incredibly glamorous: she's refreshingly average. She gets nervous around new people, and becomes exhausted running up stairs. She sometimes wears a dress and heels, and sometimes falls asleep dribbling on her hoodie.

At some points in her story she's muscular and slim, at others she's heavier and curvier. We see her in her bra at the gym, and fully-covered in her superhero costume. The whole point is her normality. What makes her exceptional is her intelligence: her ability to join the dots, make connections and see the links between things, illustrated by Sarah Zaidan through the comic's complex MindMaps. For Cat, smart is a superpower.