Stephen Fry is in danger of becoming a ‘national treasure’, the term applied to people in the public eye who have managed to find the stamina and resilience to live through the praise and the brickbats of the media, and keep performing nevertheless. Whatever happens now, he will have left an impressive legacy to popular culture, from his comedy acting in A Bit of Fry and Laurie, Blackadder and Jeeves and Wooster, to his novels like The Liar and The Hippopotamus, his narration of the Harry Potter books, his earlier memoirs and his television game show, IQ. No matter what time of day and night you turn the television on, an old episode is playing somewhere, which might be normal for American friends, but is still a bit disconcerting in the UK.

Stephen Fry is in danger of becoming a ‘national treasure’, the term applied to people in the public eye who have managed to find the stamina and resilience to live through the praise and the brickbats of the media, and keep performing nevertheless. Whatever happens now, he will have left an impressive legacy to popular culture, from his comedy acting in A Bit of Fry and Laurie, Blackadder and Jeeves and Wooster, to his novels like The Liar and The Hippopotamus, his narration of the Harry Potter books, his earlier memoirs and his television game show, IQ. No matter what time of day and night you turn the television on, an old episode is playing somewhere, which might be normal for American friends, but is still a bit disconcerting in the UK.

And throughout it all, Stephen Fry has remained a remarkably coherent character. His voice is so easily conjured up in the imagination, his face so familiar and so redolent of what we believe is his real self. I remember a colleague telling me that he’d just decided to go and watch Fry playing the lead role in the new Oscar Wilde biopic when he walked into the SCR and overheard the film being discussed, the comment being made that Fry ‘played Wilde like a self-satisfied Winnie-the-Pooh’. ‘And I thought to myself, oh thank you very much,’ my colleague told me. ‘Now I’ll never get that image out of my head.’

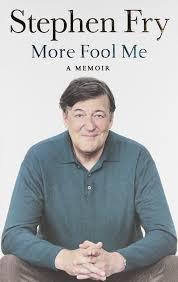

But what of the man behind the Winnie-the-Pooh mask? Stephen Fry has been parcelling out his memoirs over the years and has currently reached his third volume, one that roughly covers the era 1984-1993, or in keeping with the spirit of the book, his cocaine years and the time of his rise to fame. More Fool Me opens, however, with a 70-page synopsis of the two books that preceded, covering his rural childhood living in a large rambling house with servants but little in the way of income, his father a sort of Caracticus Potts figure, creating mad and brilliant inventions in the barn. There’s some issue there that isn’t fully eviscerated, but Fry ends up a very clever, very troubled teen, cruising towards an eventual jail sentence for credit card theft. He then worked hard to get into Cambridge where life came right for him with his Footlight friends – Emma Thompson and Tony Slattery among them – and his subsequent career writing and performing.

‘I consider myself incompetent when it comes to the business of living life,’ Fry writes. ‘There was ever something darker, more dangerous and – let’s be frank – more stupid about me than about my friends. Socially, psychologically and inwardly stupid. Imbecilic. Self-destructive. More of a fool.’ The self-excoriation comes as a prelude to his account of cocaine addiction, and I always find it fascinating to read people writing about things they have done in life which they know will be viewed poorly. I have this theory that it is almost impossible to avoid self-justification. Only the most brilliant writers can do it, because a) you need to have reached a certain level of wisdom to be a brilliant writer and b) they put the narrative first, above the demands of ego. Sometimes being a bit bonkers helps, too. But Stephen Fry goes a much more classic route – he beats himself up and then he reaches for the familiar justifications: he wants to belong, he’s fascinated by transgression, he just plain likes the experience of it (and doesn’t suffer too much from evil side effects). More intriguing to me was the list he posts at the start of the chapter of places he’s snorted coke. It begins with Buckingham Palace, continues with Windsor Castle and the House of Lords, and trots gently through every famous club, hotel and restaurant you might ever have heard of, including The Ritz and the Savoy, The Garrick and The Groucho, before ending with BBC studios, 20th Century Fox and the offices of all the major newspapers. Now what is that list really trying to say?

Not that he’s incompetent at living, I might suggest. The middle section of the memoir is a hodge-podge of anecdotes about events like Charles and Di dropping in for tea, and room-sitting a suite at Claridges where he hosts a dinner party for great elderly thesp Sir John Mills and his wife. Names drop like summer rain. And this section is followed by a diary he kept in the early 90s in which he manages to write a 90,000 word novel over the course of about 6 weeks, immediately followed by a period of creating sketches with Hugh Laurie for the show they did together, as well as earning a healthy living from voiceovers and making a dizzying number of public appearances. To say Fry has a prodigious capacity for both work and play is a wild understatement. The amount of performing, creating and hob-nobbing he gets through is eye-popping. It’s no wonder he took cocaine though, to be fair, that novel gets written while he’s at a health farm. Lesson number one to all would-be stars: you must have outrageous amounts of energy, and be able to perform well off the cuff, hungover and without sleep. That’s the secret to success.

But where is Stephen Fry in all this? I wondered in the end whether he even knew himself. This is a period of his life in which he is celibate, not something that’s up for discussion. And the discussion of drug taking feels, oh I don’t know, just not quite convincing. The ‘Stephen Fry’ living the high life on the crest of a stellar career doesn’t tally with the breast-beating author who opens and closes the memoir, berating his stupidity and incompetence. ‘Where might my life have led me if I had not all but thrown away the prime of it as I partied like one determined to test its limits?’ he asks, without providing an answer. You can’t call productivity like his ‘throwing life away’ by any score. ‘I became something of a licensed fool in palaces and private houses,’ he writes as if any of the previous anecdotes actually reflected on him in a bad way. Of course, 1995 saw his breakdown and his subsequent diagnosis as bipolar, so maybe this is more a trailer for volume four than a conclusion. And a lot of the people he might want to write about are still alive, so there are evidently all kinds of stories he cannot tell. But my own feeling is that the answer lies in his childhood sensation ‘of being watched and judged.’ That sensation leads to consummate, life-long performers, and perhaps what Fry can’t even manage to say himself is that this performance took over every part of his life, and he needed cocaine to continue to function at that vertiginous level without losing his nerve and looking down.

This is an interesting memoir if, like me, you enjoy taking a scalpel to subtext, but I think the volumes that preceded it, Moab Is My Washpot and The Fry Chronicles are probably much more satisfactory from the point of view of writing and event. Though if you like theatrical reminiscences, Fry always tells a good anecdote.