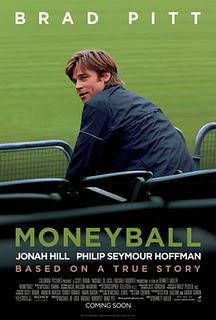

"It's hard not to be romantic about baseball," Oakland As GM Billy Beane (Brad Pitt) sighs near the end of Moneyball. Clearly we've never chatted. Based on the bestseller that revolutionized America's pastime, Moneyball deals with the As' 2002 season and how Beane, along with a handful of statistical whizzes, evened the playing field by taking a team they barely scraped together with a paltry budget and broke the record for most consecutive wins in a season. It is also a film that captures the spirit of baseball as I see it, meaning that it is arduously drawn-out and involves far more math than I ever want to do when eating junk food and becoming, in theory, emotionally invested in the grab-assing of 'roided-up men.

"It's hard not to be romantic about baseball," Oakland As GM Billy Beane (Brad Pitt) sighs near the end of Moneyball. Clearly we've never chatted. Based on the bestseller that revolutionized America's pastime, Moneyball deals with the As' 2002 season and how Beane, along with a handful of statistical whizzes, evened the playing field by taking a team they barely scraped together with a paltry budget and broke the record for most consecutive wins in a season. It is also a film that captures the spirit of baseball as I see it, meaning that it is arduously drawn-out and involves far more math than I ever want to do when eating junk food and becoming, in theory, emotionally invested in the grab-assing of 'roided-up men.Moneyball opens with footage of the 2001 American League elimination game between the As and the New York Yankees, the richest team in baseball. Intertitles contrast the teams not by score or stats but budgets, positing baseball as a metaphor for class warfare that seems especially apt in the current economic climate. Still, it's hard to see the As as underdogs when 25 people split $40 million a year to play a game. So as director Bennett Miller is trying to make me shake my head at the unfairness of it all, I was already so uninterested that the one thing that drew my eye was how incredibly old TV footage from exactly one decade ago looks.

The problem with Moneyball is that it reads as if Aaron Sorkin just took The Social Network screenplay and used a find-and-replace to swap out "Facebook" for "baseball" without bothering to dramatize the backroom dealings of this new subject. In fact, had anyone else but Sorkin (along with co-writer Steve Zaillian) written this then Sorkin would be in court with that person right now suing for IP infringement. When Beane, desperate to put together a team after richer franchises gut him for his only capable players, starts using statistics to find the best players he can afford, he faces not one obsolete Eduardo Saverin but a sea of naysayers. Zuckerberg's Asbergian alienation becomes Beane's managing isularity. And the constant flashbacks to Billy's own youth of being courted by the big leagues takes every previously thin allusion to Citizen Kane and makes them so overt I kept craning my head around young Billy Beane to see if I could spot a sled in the background.

Pitt plays Beane with a detachment he wants to make sympathetic, but the character doesn't support the lionizing portrait he's given. Armed with Yale graduate Peter Brand (Jonah Hill, playing a composite of various people who worked with the GM), Beane made his team better by ruthlessly cutting and undermining people who understandably hated an approach that invalidated their entire professional lives. For all his talk of baseball's romanticism, Beane sure has little issue with dispensing with whatever humanity the sport has to focus solely on numbers. When he gives second chances to washed-up pitcher with a shot elbow (the always endearing Chris Pratt) or a fading star so old the Yankees actually pay the As to take him off their hands, he does so not as a show of giving neglected and undervalued players a chance but a cynical measuring of their affordable worth. And when this gambit pays off, Beane wastes no time wheeling and dealing to get better players with his newfound clout, forcing some of the injured and overlooked players to be traded or even sent to the minors to make room for more solid athletes. For a movie that places so much weight on the idea of Beane being the person to rejuvenate baseball and get it back to the spirit of the game instead of focusing all on money, it neglects to point out that "moneyball" refers to the kind of game he plays.

The film's strongest yet least utilized element concerns the war of wills between Beane and his team manager Art Howe (Philip Seymour Hoffman), who views Beane's strategy of betting on misfits and has-beens based on calculated strengths in esoteric fields like on-base averages as insanity and career suicide. Hoffman, with a shaved head and a mounting look of pure fear as Beane's gamble proves intially disastrous, brilliantly channels his put-upon loser skill into the coach, shaking his wristwatch in agitation as he walks away from an unsuccessful contract renegotiation and looking like a dethroned monarch when Beane trades his favorite players to prove a point. Though focusing more fully on this conflict might have reduced the story's more far-reaching implications to a two-man battle, Hoffman and Pitt are so compelling and vicious together that I wish the whole film had revolved around their petty power plays. I also greatly enjoyed Hill, who plays against his usual frantic type to be the collected, shyly nervous foil to Beane's brash behavior, routinely stealing scenes from Pitt's furrowed brow and arrogant confidence.

But so much about this film is not merely extraneous and "Hollywood" but depressingly predictable and occasionally troubling. Talking heads constantly overlap on the soundtrack to put the pressure on the team to succeed, and the baseball scenes occur in chiaroscuro abstraction, placing a batter or a pitcher against black voids and cutting out all the noise until it becomes a crutch and a gimmick. When the As prepare for their first game with a cloud of doubt over them, a local TV reporters comes and behaves in a manner that honestly makes me unable to describe her without using a highly offensive and sexist word. Local sports journalists conduct themselves with a thirst for hard-hitting answers roughly comparable to the people who cover awards show red carpets. For her to viciously hammer these players for not being good enough is a flight of fancy that only gives more ammo to those shooting down Sorkin's rep as a feminist. We also get a portrait of masculine weakness in the form of Beane's ex-wife's new hubby, who knows nothing about sports and even speaks in airy, effeminate voice.

Moneyball's syrupy, downbeat underdog ending uses all kinds of tricks to lure the audience into sentimental bliss, from exploiting the emotional pull of a child (a singing child, no less) to validating Beane while still positioning him as a humble victor. But the true tenor of the film's ending and what it means for baseball is not one of rebirth but "Meet the new boss, same as the old boss." The same was true of The Social Network, but there it was the somber punchline, not the victorious dénouement.